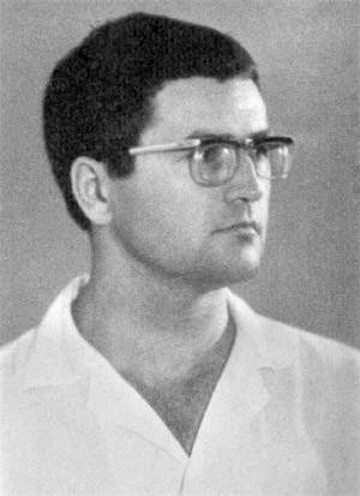

Dziuba, Ivan

Dziuba, Ivan [Дзюба, Іван; Dzjuba], b 26 July 1931 in Mykolaivka, Volnovakha raion, Donetsk oblast, d 22 February 2022 in Kyiv. Literary scholar, publicist, and a former Ukrainian dissident and government minister; full member of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine (NANU) since 1992. He studied at the Donetsk Pedagogical Institute (1949–53), was a graduate student at the Institute of Literature of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR (1953–56), and headed the literary-criticism section of the literary journal Vitchyzna (1957–62). Dziuba began writing literary criticism in 1950 and became a member of the Writers’ Union of Ukraine (SPU) in 1959. In the latter half of the 1950s he wrote a series of articles criticizing the ‘graphomania’ and provincialism evident in Soviet Ukrainian literature (reprinted in his collection Zvychaina liudyna chy mishchanyn [An Ordinary Human Being or a Philistine], 1959). Dziuba was one of the spokespersons of the shistdesiatnyky and expressed the aspirations of the postwar generation of Soviet Ukrainian writers (such as Vasyl Symonenko, Lina Kostenko, Ivan Drach, Mykola Vinhranovsky, Vasyl Holoborodko, and many others) to revitalize Ukrainian literature and liberate it from the influence of Russian literature. He stressed the need to reject the official literary theories of the Stalinist era and to study Ukrainian literature in relation to Western European literature (eg, in his articles on Hryhorii Skovoroda and Oleksander Biletsky).

In the 1960s Dziuba became active in the movement against Russification and the persecution of the Ukrainian intelligentsia (see Dissident movement). He spoke at a public demonstration protesting the mass arrests in Ukraine that was held at the Ukraina movie theater in Kyiv (September 1965) and at a commemoration of the twenty-fifth anniversary (September 1966) of the Babyn Yar massacre, where he forcefully denounced official and popular anti-Semitism in Soviet Ukraine. Along with other dissidents he signed various petitions in defense of political prisoners. His writings and political activities led to his dismissal from his job at Vitchyzna and later his job as a consultant for the Molod publishing house (1964–65).

Late in 1965 Dziuba completed his main work, Internatsionalizm chy rusyfikatsiia? (Internationalism or Russification?), which he submitted to Petro Shelest, first secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine (CPU), and Volodymyr Shcherbytsky, chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Ukrainian SSR, as a document for consideration. In it he demonstrated how the Soviet regime had departed from the theoretical principles of Leninist nationality policy and had been Russifying Ukraine and destroying its society and intelligentsia under the pretext of internationalism—in effect, how the Soviet government was perpetuating the colonial policies of tsarist Russia. This work circulated widely in samvydav form and solidified Dziuba’s stature as a charismatic dissident figure. It was published in the West in 1968 and was subsequently translated into Russian, English, French, and Italian—providing a fundamental source of information on contemporary Ukraine.

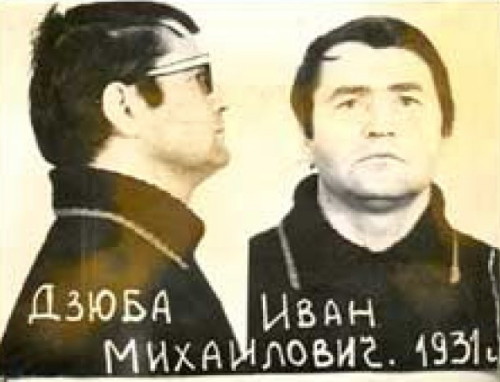

Dziuba’s underground popularity was tolerated (but not condoned) for some time by the CPU because his writings and public speeches were not condemnations of the Soviet system, but rather pleas for its reform. All the same, from 1965 Dziuba ceased to be published in the USSR and was kept under close surveillance. In January 1972 he was arrested, and in April he was expelled from the SPU (an earlier decision by its Kyiv branch to expel Dziuba in the fall of 1969 had been overturned by the SPU’s Plenum early in 1970). In April 1973 he was sentenced to five years’ imprisonment; he was released in November after he wrote a public recantation of his views. From then until the early 1980s Dziuba lived in relative isolation: although he worked as a correspondent and proofreader for a minor Kyiv periodical, he was not readmitted to the SPU until 1980 and was in effect removed from the literary scene.

Dziuba was strongly condemned for recanting by members of the Ukrainian dissident movement (notably Valentyn Moroz and Leonid Pliushch). In 1978 his book Hrani krystala (Facets of a Crystal), a repudiation of Internationalism or Russification?, appeared. In 1980 Dziuba was readmitted into the SPU. For the next few years he occasionally published tame literary criticism in Soviet journals. A book of his literary essays, Na pul’si doby (On the Pulse of the Age), appeared in 1981.

Dziuba emerged as an important spokesperson for Ukrainian interests during Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika and then became a major cultural official in the period following the 1991 Ukraine’s Declaration of Independence. He has served as the first president of the Republican Association for Ukrainian Studies (1988–91; now National Association for Ukrainian Studies); Ukraine’s minister of culture (November 1992-August 1994); academic secretary of the NANU Division of Literature, Language, and Art History (since 1996); and joint editor-in-chief of Suchasnist’ (1991–2000); and now heads its editorial board and is the joint editor-in-chief of the new Entsyklopediia suchasnoï Ukraïny (Encyclopedia of Contemporary Ukraine) project based at the NANU. Dziuba has been a member of numerous governing bodies, including the Language Policy Council of the Presidential Administration (February 1997–November 2001) and the Shevchenko National Prize Committee, which he has chaired since July 1999.

In the second half of the 1980s, Dziuba emerged as one of the most important Ukrainian publicists and literary critics of the day. After publishing a collection of essays on Soviet Ukrainian literature entitled Avtohrafy vidrodzhennia (The Autographs of a Renaissance, 1986), he produced several important contributions to the study of Taras Shevchenko. His comparative study of Shevchenko’s and A. Khomiakov’s attitudes toward Pan-Slavism (U vsiakoho svoia dolia [Everyone Has One’s Own Fate], 1989) challenged a number of prescribed principles of Soviet-era Shevchenko studies by presenting Shevchenko’s views as contrary to those of the Russian Pan-Slavists and as advocating Ukrainian political independence. Dziuba’s post-Soviet essays on Shevchenko’s legacy represent a complete departure from the set political formulas of Soviet-era Shevchenko criticism. For example, his study of Shevchenko’s poem Kavkaz (Zastukaly serdeshnu doliu... [They Cornered Our Wretched Fortune..., 1995]), was focused on a critique of Russian imperialism as exemplified by the history of the Russian conquest of the Caucasia. A compilation of Dziuba’s speeches on cultural topics, literary studies, and sketches appeared as Mizh kul’turoiu a politkykoiu (Between Culture and Politics, 1998); and his selected literary studies, including most of his essays on Shevchenko’s legacy, were published in Z krynytsi lit (From the Wellspring of Years, 2001). He published two other studies of Shevchenko in the 2000s: Taras Shevchenko (2005) and Taras Shevchenko: Zhyttia i tvorchist’ (Taras Shevchenko: Life and Works). In 2010 he published a historical study of Ukrainophobic trends in Russian nationalism Nahnitannia moroku: Vid chornosotentsiv pochatku XX stolittia do ukrainofobiv pochatku stolittia XXI (Spreading the Darkness: From the Black Hundreds of the early 20th century to the Ukrainophobs of the early 21st century).

Ivan Koshelivets, Marko Robert Stech

[This article was updated in 2011.]

.jpg)

.jpg)