Ukrainian Insurgent Army

Ukrainian Insurgent Army [Українська повстанська армія (УПА); Ukrainska povstanska armiia (UPA)]. A Ukrainian military formation which fought from 1942 to 1949, mostly in Western Ukraine, against the German and Soviet occupational regimes. Its immediate purpose was to protect the Ukrainian population from German and Soviet repression and exploitation; its ultimate goal was an independent and unified Ukrainian state.

The first UPA units appeared in western Volhynia (now Volhynia oblast and Rivne oblast). They were organized independently by Taras Borovets (in spring 1942), the OUN (Bandera faction) (from October 1942), and the OUN (Melnyk faction) (in spring 1943). As resistance to the Germans intensified, the military forces of the Bandera faction grew rapidly and established their control over many districts of Volhynia. When talks on unification among the three groups failed, the most powerful group, the Bandera units, disarmed and absorbed the two other groups, in July and August 1943. Klym Savur, the leader of the OUN (B) for northwestern Ukraine, became the commander in chief of the unified UPA.

German auxiliary police and guard units, composed not only of ethnic Ukrainians but also of other nationals who had served in the Red Army, defected to the UPA. The number of non-Ukrainian UPA soldiers grew rapidly, and peaked in the late fall of 1943. They were organized into separate national units, the largest of which were the Azerbaidzhani, Uzbek, Georgian, and Tatar. In the autumn of 1943 the UPA established a secret armistice with Hungarian units which guarded German communication lines in Volhynia. Recognizing the importance of national aspirations, the UPA organized on 21–22 November 1943 the Conference of the Oppressed Nations of Eastern Europe and Asia. It was attended by representatives of 13 nationalities, who resolved to support each other's liberation struggles.

Beginning in the summer of 1943, UPA units from the northwestern region conducted southward raids into Kamianets-Podilskyi oblast and Vinnytsia oblast to undermine German control of this territory and to build up local insurgency forces. By the late autumn a new military grouping was consolidated under the command of Vasyl Kuk, the OUN leader for central Ukraine.

In the first two years of the German occupation the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) used Galicia as a training and supply area for the UPA. When a successful recruitment drive for the Division Galizien was launched, in May–June 1943, and a large detachment of Soviet partisans (see Soviet partisans in Ukraine, 1941–5) led by Sydir Kovpak made its way through Galicia into the Carpathian Mountains, in July 1943, the OUN decided to form military units in Galicia as well. Commanded by Oleksander Lutsky, these units were at first called the Ukrainian People's Self-Defense (UNS). As insurgent activity increased, the Germans placed Galicia under martial law, in October 1943. This only provoked stronger resistance.

A single command for all three regions of Ukraine, the Supreme Command of the UPA, was set up on or about 22 November 1943. The command consisted of the supreme commander and the Supreme Military Headquarters or General Staff, which was headed by the chief of staff (who was also the deputy commander) and was divided into six sections: operations, intelligence, logistics, personnel, training, and political-education. Lt Col Roman Shukhevych was appointed commander in chief, and Maj Dmytro Hrytsai became chief of staff. The original UPA in Volhynia was named officially the UPA-North, the insurgent units in central Ukraine became the UPA-South, and the Ukrainian People's Self-Defense in Galicia was renamed the UPA-West. With Maj Vasyl Sydor's appointment to commander of the new UPA-West in January 1944, the reorganization of the unified UPA was completed. Each of the three krais of the UPA was subdivided into military districts. At the beginning of 1944 there were at least 10 districts in total: 2 in the UPA-North, 6 in the UPA-West, and 2 in the UPA-South. In 1945 each district was subdivided into tactical sectors. Every district and sector had its commander and headquarters analogous to the General Staff. This territorial organization of the UPA remained unchanged during the active combat period until 1949. To broaden the social and political base of the armed struggle for Ukraine's independence, the Supreme Command of the UPA took the initiative in setting up the Ukrainian Supreme Liberation Council (est 15 July 1944), which served as a provisional government expressing the political will of the insurgency movement.

The basic combat unit during most of the UPA's history was a company of 120 to 180 men. The standard UPA company had three platoons each with three squads (10 to 12 men armed with a light machine gun, two or three automatic weapons, and seven or more rifles). In 1943–5 most companies were organized into kurins (two to four companies per kurin), and under special conditions two or more kurins were combined into a zahin. A kurin commander's staff included a political-education officer, an adjutant, a sergeant major, and sometimes a chaplain and a medical doctor. Regardless of size, all combat units within one military district formed a group (hrupa). The UPA did not receive aid from other countries; weapons, ammunition, medical supplies, and uniforms had to be seized from the enemy. Although it deployed some cavalry and artillery units during 1943–4, the UPA was basically an infantry force. According to some German intelligence reports in 1944, its strength was 200,000. According to a Soviet source (1988), in 1944–6 some 56,600 UPA soldiers were killed, 108,500 were captured, and 48,300 surrendered voluntarily. According to UPA historians in the West, at its peak in 1944 the army had at least 25,000 and at most 40,000 men.

The UPA made use of two rank systems, a functional one and a traditional formal one (see Military ranks). The functional system was instituted because of an acute shortage of qualified and politically reliable officers during the early stages of organization. Those who demonstrated leadership ability were appointed to command positions regardless of formal rank or training. The most critical leadership shortages were found at the lower levels, ie, the platoon and squad. Almost every district organized its own NCO school, lasting four to six weeks, but the demand for qualified squad leaders could not be met. A severe shortage of medical officers was alleviated partly by enlisting Jewish doctors, who willingly joined the anti-Nazi resistance. The UPA also ran formal officer candidate schools, which produced approx 690 graduates. (For the UPA's award system see Military decorations.)

Publishing was usually the responsibility of the political-education section. The UPA printed journals, such as Do zbroï (1943) and Povstanets’ (1944–6); newspapers; military textbooks; pamphlets for youth; and leaflets. Some military districts and tactical sectors published their own irregular periodicals (eg, Shliakh peremohy, Chornyi lis, and Lisovyk). The best-known contributors to the UPA press were Ya. Busel, Petro Poltava, Osyp Diakiv, and the artists Nil Khasevych and Mykhailo Chereshnovsky.

During 1943 the UPA staged some successful ambushes and battles against the Germans, establishing its control of the countryside in Volhynia and leaving only the towns in German hands. At the same time it cleared some of the region of Soviet partisans and expanded its power southward and eastward. In 1944 it fought its largest engagements with German and Soviet forces. Retreating German units were frequently ambushed for their weapons and supplies. German attempts to secure areas of the Carpathian Mountains in the summer of 1944 led to several pitched battles with the UPA-West. But the main threat to the UPA was the Soviet NKVD combat troops that arrived in the rear of the advancing Red Army with the special task of re-establishing Soviet power.

During the first half of 1944 numerous ambushes, skirmishes, and large-scale battles occurred between NKVD forces and the zahony of the UPA-North and UPA-South. In February Gen N. Vatutin, Soviet commander of the First Ukrainian Front, was mortally wounded in an ambush. On 24 April 30,000 NKVD troops encircled and fought 5,000 soldiers of the UPA-South at the Battle of Hurby. Modifying its tactics according to experience, the UPA gradually dispersed its larger units and operated mostly with companies which held specific territories and staged occasional propaganda raids into uncontrolled areas or neighboring countries. The first large-scale NKVD offensive against the UPA was conducted in the winter of 1944–5 in the Carpathian Mountains region. The UPA managed to preserve its control of the countryside and scored successful attacks against Soviet administrative centers and garrisons. With the ending of the war the returning Red Army divisions were turned against the UPA in the summer of 1945. The results were disappointing to the Soviet regime, but its offer of amnesty to soldiers surrendering by 20 July 1945 appeared more successful. Many men evading induction into the Red Army gave themselves up. The UPA used this opportunity to send home some discouraged or disabled soldiers. By 1949 there were at least four more amnesty calls.

The ‘Great Blockade’ in the Carpathian Mountains from January to April 1946 was the only successful Soviet offensive against the UPA. Special contingents of NKVD troops were stationed in all the towns and villages, and mobile combat units scoured the forests. Denied food and shelter, and forced to fight on the march at extremely low temperatures, the UPA experienced casualties of 40 percent. The Supreme Command decided to demobilize most combat units and ordered their surviving members to continue the struggle underground. The UPA command structure (krai, military district, and tactical-sector headquarters), however, continued to function.

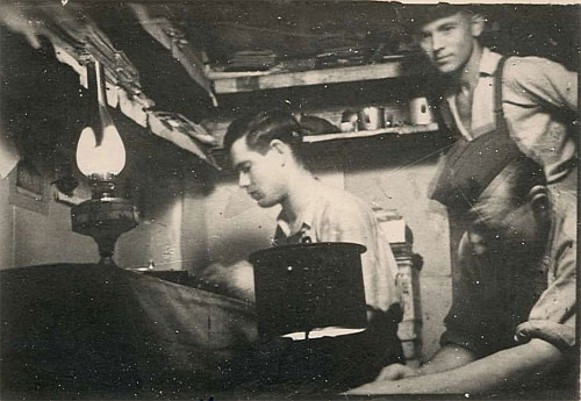

The demobilization order did not apply to the forces of the Sixth Military District—the Sian Division of the UPA-West—which operated in Ukrainian ethnic territories that were annexed by Poland after 1944. The division defended the Ukrainian population from forced deportations to the USSR in 1945 and 1946. Having reached an understanding with the Polish Home Army, it conducted several joint operations against Polish security forces. On 28 March 1947 Gen K. Świerczewski, the deputy defense minister of Poland, was killed in an ambush by the Lemko Company of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army under Lt Stepan Stebelsky (‘Khrin’). In the spring and summer of 1947 the Polish authorities staged Operation Wisła, in which the remaining Ukrainian population was deported by force to other parts of Poland. UPA battle losses went up sharply, and the surviving units were ordered either to cross into the USSR or to march across Czechoslovakia to West Germany. Remnants of Company 95, led by Lt M. Duda (‘Hromenko’), reached West Germany on 11 September 1947 (photo: Company 95 soldiers in Germany).

Some UPA units continued to operate in 1948 and 1949 in the Carpathian Hoverlia Military District (see Hoverlia (4th) Group of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army). They were usually composed of two platoons of two squads each, and had a total strength of 30 to 50 veteran noncommissioned officers. Except for two units, they were demobilized at the end of the summer of 1948. On 3 September 1949, Roman Shukhevych ordered the command structure and the remaining combat units to be deactivated, and their members to be transferred to the underground network. After Shukhevych's death (5 March 1950) the underground continued the armed struggle under Vasyl Kuk's (‘Koval's’) leadership until 1954.

(See also Graywolves Company of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, Lviv (2nd) Group of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, Lysonia (3rd) Group of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, and Former Members of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army.)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hrafika v bunkrakh UPA (Philadelphia 1952)

Shankovs’kyi, L. ‘Ukraïns’ka Povstancha Armiia,’ in Istoriia ukraïns’koho viis'ka (Winnipeg 1953)

Tys-Krokhmaliuk, Yu. UPA Warfare in Ukraine: Strategical, Tactical, and Organizational Problems of Ukrainian Resistance in World War II (New York 1972)

Szcześniak, A.; Szota, W. Droga do nikąd (Warsaw 1973)

Shtendera, Ie.; Potichnyi, P. (eds). Litopys Ukraïns'koï povstans'koï armiï, vols 1–53 (Toronto 1976–2017)

Potichnyj, P.; Shtendera, Ye. (eds). Political Thought of the Ukrainian Underground, 1943–1951 (Edmonton 1986)

Lebed’, M. Ukraïns’ka povstans’ka armiia (1946; 2nd rev edn, np 1987)

Sodol, P. UPA: They Fought Hitler and Stalin: A Brief Overview of Military Aspects from the History of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, 1942–1949 (New York 1987)

Huk, B. (comp and ed). Zakerzonnia: Spohady voiakiv Ukraïns’koï Povstans'koï Armiï, 2 vols (Warsaw 1994)

Sodol’, P. Ukraïns’ka Povstans'ka Armiia, 1943–49: Dovidnyk (New York 1994)

Serhiichuk, V. (ed). OUN-UPA v roky viiny: Novi dokumenty i materialy (Kyiv 1996)

Burds, J. ‘AGENTURA: Soviet Informants' Networks and the Ukrainian Underground in Galicia, 1944–48,’ East European Politics and Societies, 11, no. 1 (Winter 1997)

Drozd, R. Ukraińska Powstańcza Armia: Dokumenty-struktury (Warsaw 1998)

Kentii, A. Narys borot’by OUN-UPA v Ukraïni, 1946–1956rr. (Kyiv 1999)

Zdioruk, S.; Hrynevych, L.; Zdioruk, O. Pokazhchyk publikatsiï pro diial’nist’ OUN ta UPA, 1945–1998 rr. (Kyiv 1999)

Motyka, Grzegorz. Tak było w Bieszczadach: Walki polsko-ukraińskie 1943–1948 (Warsaw 1999)

Pyskir, Maria Savchyn. Thousands of Roads: A Memoir of a Young Woman's Life in the Ukrainian Underground During and After World War II (Jefferson, NC–London 2001)

V’iatorovych, Volodymyr. Reidy UPA terenamy Chekhoslovachchyny (Toronto–Lviv 2001)

Stupnyts’kyi, Iu. Spohady pro perezhyte, 2nd ed (Lviv–Toronto 2004)

Motyka, Grzegorz. Ukraińska partyzantka 1942–1960: Działalność Organizacji Ukraińskich Nacjonalistów i Ukraińskiej Powstańczej Armii (Warsaw 2006)

Viatrovych, Volodymyr (ed.). Ukraïns'ka povstans'ka armiia: Istoriia neskorenykh (Lviv 2007)

Iliushyn, Ihor. Ukraïns’ka povstans’ka armiia i Armiia Kraiova: Protystoiannia v Zakhidnii Ukraïni (1939–1945 rr.) (Kyiv 2009)

Viatrovych, Volodymyr. Druha pol's'ko-ukraïns'ka viina, 1942–1947 (Kyiv 2011)

Motyka, Grzegorz. Od rzezi wołyńskiej do akcji “Wisła”: Konflikt polsko-ukraiński 1943–1947 (Cracow 2011)

Petro Sodol

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 5 (1993). The bibliography has been updated.]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)