Nechui-Levytsky, Ivan

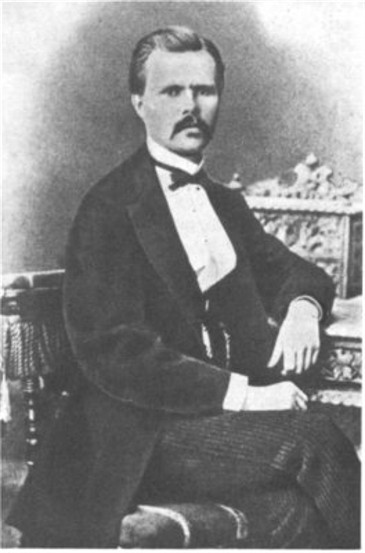

Nechui-Levytsky, Ivan [Nečuj-Levyc’kyj] (pseud of Ivan Levytsky; other pseuds: I. Nechui, I. Bashtovy, Hr. Hetmanets, O. Krynytsky), b 25 November 1838 in Stebliv, Kaniv county, Kyiv gubernia, d 15 April 1918 in Kyiv. (Photo: Ivan Nechui-Levytsky.) Writer. Upon graduating from the Kyiv Theological Academy (1865) he taught Russian language, history, and geography in the Poltava Theological Seminary (1865–6) and, later, in the gymnasiums in Kalisz, Siedlce (1867–72), and Kishinev (1873–4). He began writing in 1865, but because of Russian imperial censorship his works appeared only in Galician periodicals, such as the journal Pravda, Dilo, and Zoria (Lviv). The first to be published were two stories, ‘Dvi moskovky’ (Two Muscovite Women) and ‘Horyslavs’ka nich, abo Rybalka Panas Krut’ (A Night in Horyslav, or Panas Krut the Fisherman), both of which appeared in Pravda in 1868. He mainly wrote stories, in which he combined the styles of the novel and the folkloric narrative. His works about the lives of peasants and laborers established him as a master of Ukrainian classical prose and as the creator of the Ukrainian realist narrative. They include Mykola Dzheria (1878), Kaidasheva sim'ia (Kaidash's Family, 1879), Burlachka (The Wandering Girl, 1880), Ne toi stav ([He] Changed, 1896), and the cycle of short stories Baba Paraska ta baba Palazhka (Granny Paraska and Granny Palazhka, 1874–1908). The Ukrainian clergy was described and satirized in Starosvits’ki batiushky ta matushky (Old-World Priests and Their Wives, 1888), Pomizh vorohamy (In the Midst of Enemies, 1893), and Afons’kyi proidysvit (The Vagabond from Athos, 1890). The Polish aristocracy and the Polonized Ukrainian middle class are portrayed in Prychepa (The Hanger-on, 1869) and Zhyvtsem pokhovani (Buried Alive, 1898). Nechui-Levytsky was the first to provide fictional characterizations of various classes of the Ukrainian intelligentsia, ranging from students and teachers to high-ranking members of the Russian civil service. Against a background of colonial repression and thoroughgoing Russification Nechui-Levytsky sought to depict the stirrings of national consciousness in the Ukrainian intelligentsia and their attempts to ‘place first on the agenda the inevitability of national liberation’ (Oleksander Biletsky). Those attempts on the part of his protagonists usually bring about their downfall. Such is the theme of Khmary (Clouds, 1874), the first Ukrainian work of fiction to address the problem, of Nad Chornym Morem (On the Black Sea Coast, 1890), of Navizhena (The Madwoman, 1891), and of many other works. Nechui-Levytsky also wrote historical fiction (mainly under the influence of Mykola Kostomarov), including Zaporozhtsi (The Zaporozhians, 1873), Kniaz’ Ieremiia Vyshnevets’kyi (Prince Jeremi Wiśniowiecki, 1897, first pub 1932), and Het’man Ivan Vyhovs’kyi (Hetman Ivan Vyhovsky, 1899). His plays included the historical dramas Marusia Bohuslavka (1875) and V dymu ta polum'ï (In the Smoke and the Flames, 1911), the comedies Na Kozhum'iakakh (In Kozhumiaky; adapted by Mykhailo Starytsky in 1875 and published as Za dvoma zaitsiamy [Chasing After Two Hares]) and Holodnomu i open’ky m'iaso (For a Starving Man Even Mushrooms Are Meat, 1887), and children's interludes.

Nechui-Levytsky also wrote popular works on Ukrainian mythology, history, and ethnography, and numerous articles about Ukrainian theater and the various people active in it. In his articles on Ukrainian literature, such as ‘S'ohochasne literaturne priamuvannia’ (The Contemporary Literary Trend, 1878, 1884) and ‘Ukraïnstvo na literaturnykh pozvakh z Moskovshchynoiu’ (The Ukrainian Community in Literary Litigation with Russia, 1891), he championed the idea of a national literature formed independently of outside influences, and asserted that ‘Russian literature is useless [as a model] for Ukraine.’

In the field of linguistics Nechui-Levytsky was categorically opposed to the dissemination of the Galician variant of the literary Ukrainian language and to the orthography adopted in Galicia in the 1890s and 1900s. His polemical brochures S'ohochasna chasopysna mova na Ukraïni (Contemporary Language of the Press in Ukraine, 1907) and Kryve dzerkalo ukraïns’koï movy (The Distorted Mirror of the Ukrainian Language, 1912) were written in the spirit of conservative romanticism. He argued for a pure national lexicon and phraseology that was to be kept clean of all neologisms and foreign expressions. In his own works, however, he frequently used the grammatical and lexical dialectal forms of the nearby Russian territories, and he refused to allow any corrections. His inconsistency is most evident in his amateurish Hramatyka ukraïns’koho iazyka (A Grammar of the Ukrainian Language, 1914).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

‘Zhyttiepys’ Ivana Levyts’koho (Nechuia), napysana nym samym,’ S’vit, no. 7 (1888)

Iefremov, Serhii. Nechui-Levyts’kyi (Kyiv 1924)

Mezhenko, Iurii. ‘Ivan Semenovych Nechui-Levyts’kyi,’ Tvory, 1 (Kyiv 1926)

Bilets’kyi, Oleksander. ‘Ivan Semenovych Levyts’kyi (Nechui),’ Tvory v chotyr’okh tomakh, 1 (Kyiv 1956)

Pokhodzilo, M. Ivan Nechui-Levyts’kyi (Kyiv 1960)

Krutikova, N. Tvorchist’ I.S. Nechuia-Levyts’koho (Kyiv 1961)

Ivanchenko, R. Ivan Nechui-Levyts’kyi: Narys zhyttia i tvorchosti (Kyiv 1980)

Bohdan Kravtsiv, Oleksa Horbach

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 3 (1993).]

.jpg)