Holocaust

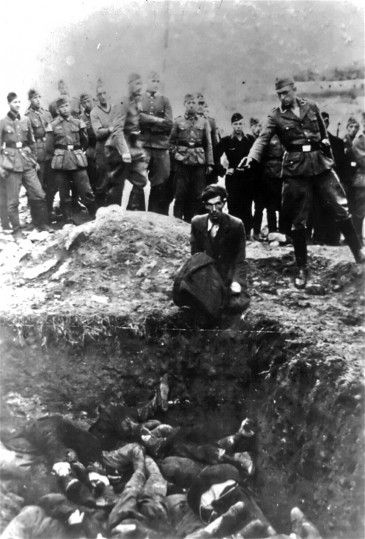

Holocaust. Ukraine was a major site of the implementation of Nazi Germany's genocidal policies toward the European Jews during the Second World War. When Germany invaded the USSR in June 1941, the Ukrainian SSR, including the newly annexed territories of eastern Galicia and western Volhynia, had a Jewish population of 2.3 million. Two out of three of Ukraine's Jews—between 1.4 and 1.5 million men, women, and children—were murdered under gruesome circumstances during the subsequent eighteen months.

Ukraine's Jewish communities were concentrated in the western half of the country, especially in Galicia and Volhynia, but also in Podilia. That is why most of Ukraine's Jews were not able to escape or be evacuated in the face of the rapid German advance until August 1941. Only in Southern Ukraine and Left-Bank Ukraine were most of them able to leave before the Wehrmacht arrived. According to general estimates based on overall Soviet evacuation statistics, 800,000 to 900,000 Jews fled from Ukraine during the massive Soviet evacuation to the east.

From the first days of the Nazi occupation of Ukraine, the Third Reich's military and police apparatus increasingly persecuted and murdered Jews, as it did in Poland, Russia, Belarus, and elsewhere in Nazi-occupied Europe. Before the invasion of the USSR, the Nazi police and Wehrmacht had planned the killing of rather limited groups there. All Jewish functionaries in the Soviet Communist Party and state apparatus were explicitly targeted for extermination, as were all political commissars in the Red Army, whom the Nazis incorrectly believed to be predominantly Jewish. Some Wehrmacht units were prepared to apply “special treatment” to surrendered and captured Soviet prisoners of war of Jewish origin. The overall background to the Nazis' plans indicates that violence on a much broader scale against the Soviet population, and especially against the Jews, had been foreseen. Most inhabitants of the occupied Soviet cities—where most Jews lived—would not be supplied with food. Thus the Nazis calculated that many millions would starve if they were unable to flee.

Most historians do not assume there was a general order for the SS and Nazi police to kill all Jews before the invasion of the USSR. Nevertheless, in addition to the orders concerning functionaries of Jewish origin, the leaders of the SS and German police units were granted considerable freedom of action in what they considered necessary for securing their area of responsibility. Furthermore, these units planned to instigate anti-Jewish pogroms by local inhabitants. It has not yet been clarified whether this was included in the pre-invasion discussions between the German military intelligence service (the Abwehr) and some leaders of the Bandera faction of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN).

Apparently some OUN underground groups in Western Ukraine staged or incited anti-Jewish actions in their efforts to sabotage the Red Army's retreat after 22 June 1941. This became obvious after the brutal massacres of thousands of political prisoners by the NKVD before and during the Soviet evacuation eastward in the last week of June 1941. The Nazi occupiers and certain elements in the OUN and within the local Ukrainian population blamed these mass murders on the Bolsheviks and NKVD personnel of Jewish extraction and, by extension, all Jews. This anti-Semitic perception of the Jews' collective guilt lay the mental groundwork for the anti-Jewish violence that occurred in various places in Western Ukraine in late June and early July 1941. Approximately 20,000 Jews, mostly men, were killed during the commitment of the crimes. At the same time, the German political police, especially Einsatzgruppe C, started killing Jewish men en masse, particularly those they imagined were part of the “intelligentsia,” ie, teachers, Party members, former community leaders, and so on. Officially these mass executions were declared reprisals for the NKVD's murders, even though the latter had not been directed against the Wehrmacht but against other local inhabitants, including some Jews.

During July the SS and German police apparatus were installed throughout the Ukrainian territories occupied by the Third Reich. These forces were headed by the “higher SS and police leader of Russia-South” (later “of Ukraine”), a position held by the persons primarily responsible for the genocide—Friedrich Jeckeln and, from October 1941, Hans Prützmann. The central units under their command included Einsatzgruppe C, which was active in western and later in northern Ukraine; and Einsatzgruppe D, which was responsible for the mass killings in southern Ukraine. Beginning in the autumn of 1941, Einsatzgruppe C was gradually transformed into a stable machine directed by the chief of the German security police in Kyiv.

In the territories the Einsatzgruppen left behind during their eastward advance, regular German police units—the Ukraine Police Regiment South (police battalions 45, 303, and 314) and police battalions 304, 315 and 320—soon took over their criminal tasks. During the summer and autumn of 1941, the First SS Brigade of the Waffen-SS committed mass murders in northern Ukraine; and in the spring of 1942 a special killing unit, Sonderkommando Plath, was installed by the security police in the Dnipropetrovsk region.

General authority over the occupied territories was in the hands of the Wehrmacht and later the civil administration of the so-called Reichskommissariat Ukraine (RKU). Military administration of the front was divided among the Sixth, Seventeenth, and Eleventh Armies, while the rear was under the commander of Rear Army Group South. The military administration took all steps to persecute the Jews, similar to the measures that were undertaken in Nazi-occupied Poland. The Jews were placed outside the jurisdiction of the law, they were obligated to wear identification armbands marked with the star of David, and they were stripped of most of their belongings; the men were often conscripted for forced labour. A general Wehrmacht order allowed the creation of ghettos, but apparently this was only implemented under the RKU administration. The RKU was established on 1 September 1941 in western Volhynia, and by November 1941 its jurisdiction extended to the Dnipro River; its administration became responsible for two-thirds of Ukraine. Meanwhile, all of Galicia was transferred to the Generalgouvernement, a German occupational structure originally created for the administration of central and southeastern Poland; and in September 1941 the Odesa region became part of Transnistria, the name given to the region occupied and administered by Germany's ally Romania.

From late autumn 1941 the RKU administration began creating ghettos in the western half of Ukraine. The actual form of those ghettos varied greatly. Sometimes they consisted of a few fenced-off buildings; and sometimes all the Jews in a town were forcibly moved into a small quarter with a minimal infrastructure that was declared a ghetto but not fenced in or even guarded. Inside the ghettos nutrition and medical care were insufficient, and those Jews who did not have access to the black market or did not receive assistance from relatives were highly endangered. In each city or town with a large Jewish community, the creation of a Judenrat (Jewish Council) was made compulsory to ensure that the Germans' orders were followed, that provisions were “purchased” from them, and to distribute those provisions.

The situation east of the line connecting Zhytomyr in the north and Mykolaiv in the south was different, because in August 1941 the advancing police units began killing most if not all of the Jewish inhabitants they apprehended there immediately after occupying a place.

The first mass killings of Jewish women and children were apparently committed by the First SS Brigade already in July 1941 in Ostroh in Volhynia. But a new dimension of the genocide was marked by the massacre organized by SS leader Friedrich Jeckeln and committed by Police Battalion 320 in Kamianets-Podilskyi on 27–29 August 1941. During those three days, the police shot 23,600 Jews, including 14,000 refugees who had been expelled from Hungarian-ruled Transcarpathia only weeks before.

In September 1941 the mass-scale crimes continued farther east: on 13 September in Zhytomyr, and on 27–29 September at the Babyn Yar (Russian: Babii Yar) ravine in Kyiv. There Sonderkommando 4A, part of Einsatzgruppe C, and Police Battalions 45 and 314 shot 33,771 people, the largest massacre of the Holocaust. According to estimates, nearly 15,000 other Jewish inhabitants of Kyiv were killed by the spring of 1942. The next two large massacres occurred during the German advance into Left-Bank Ukraine: in Dnipropetrovsk 15,000 Jews were slaughtered by Police Battalion 314 on 13–14 October; and in Kharkiv 12,000 Jews were murdered by Police Battalion 314 and Sonderkommando 4A in the first days of January 1942.

During October 1941 the next stage of the “Final Solution” in Poland and the USSR took shape. Now the mass killings of Jewish women and children were extended to the areas under civil administration. In eastern Galicia these atrocities started on 6 October and were followed by “Bloody Sunday” on 12 October in Stanyslaviv (German: Stanislau; now Ivano-Frankivsk), during which Security Police Stanislau and Police Battalion 133 killed 12,000 Jewish inhabitants of that city. At the same time, in neighboring Volhynia, Police Battalions 315 and 320 murdered tens of thousands. In Rivne alone, both units and Einsatzkommando 5 shot a total of 17,000 persons on 6–9 November. Most of these mass crimes were connected to the creation of ghettos. The occupation authorities wanted to “reduce” the number of ghetto residents at the outset.

Parallel to these enormous German crimes, the Romanian occupation authorities turned Transnistria into a mass graveyard for local Jews and refugees. From August 1941 the Romanian fascist government deported the Jews of Bessarabia and Bukovyna to Transnistria, where they had to live in camps and ghettos in dreadful circumstances. Not long after the massacre at Babyn Yar, the Romanian army and police committed an almost similar crime, killing around 25,000 Jews in Odesa on 23–24 October. Most of the remaining Jews there were driven to northern Transnistria, into the ethnic German settlement areas around Berezivka, where they were immediately killed by the ethnic German Selbstschutz, an SS organization. Starting around Christmas 1941, the Romanian authorities murdered the inmates of the so-called Golta camps Akhmetchetka, Bohdanivka, and Domanivka, in which tens of thousands of Jews from other regions had been incarcerated. Most of the camps' inmates were dead by March 1942. Only in August 1942 did the Romanian government turn away from active participation in the Holocaust.

By the spring of 1942 almost no Jews remained alive in German-occupied Right-Bank and Left-Bank Ukraine. Meanwhile, in western Ukraine the perpetrators started classifying and organizing the surviving Jews according to their presumed ability to work. As a result, the murder of women and children intensified. Galician Jews selected for destruction were deported from 16 March on to the Bełżec death camp (75 km north of Lviv) in the Lublin district and were gassed to death there in sealed cells into which carbon monoxide from diesel engines was pumped. In Volhynia, Podilia, and the Mykolaiv region, mass executions were restarted at almost the same time. All the Jews in the latter region were killed by 1 April.

The most apocalyptic period was yet to come. In July 1942 approximately 600,000 Jews were still alive in Ukraine. Most of them fell victim to the extreme murder campaign that took place between July and November 1942. Almost every day German police, aided by Ukrainian auxiliary policemen, killed thousands of Jews, especially in August and September 1942. In Volhynia and Podilia nearly all ghettos and their inhabitants were annihilated. The biggest massacres occurred in Volhynia: in Lutsk on 19–23 August (14,700 victims), Volodymyr-Volynskyi in the first days of September (13,500), and Liuboml on 1–2 October (10,000).

At the beginning of 1943 only small groups of Jewish forced laborers were still alive in Reichskommissariat Ukraine, especially in camps along so-called Durchgangsstrasse IV, the road from Lviv to Dnipropetrovsk. They and the camps were liquidated during the course of that year, as was the small work ghetto in Volodymyr-Volynskyi, whose inmates were killed on 13–14 December even though they had been considered indispensable for the German war economy.

The mass-murder campaign intensified in eastern Galicia from the end of July 1942. Around 180,000 Jews were deported to the Bełżec death camp, among them 40,000–50,000 Jewish victims from Lviv during the “Great Action” of 10–25 August and another 10,000 on 19–20 November. But the “final solution” in Galicia was not finished in 1942. At the end of that year the Bełżec camp was closed down, and the police again started shooting Jews near the their places of residence. In June 1943 all remaining ghetto inhabitants were killed, and in July nearly all forced laborers were annihilated. The inmates of the Yanivska (Polish: Janówska) camp in Lviv were exterminated on 19 November, and only some forced laborers in the Boryslav oil fields remained alive and were evacuated westward in 1944.

Two specific cases must be mentioned. Forced-labor battalions consisting of Hungarian Jewish men accompanied the Hungarian army that fought on the German side in Left-Bank Ukraine. Most of these Jews were killed by German police in 1943 or died in combat. Only those Jewish refugees from Bukovyna and Bessarabia who survived the Romanian murder campaigns that ended in the summer of 1942 generally outlived the Nazi genocide.

Most of Ukraine's Jews were taken completely by surprise by the indignities, terror, and mass murders to which they were subjected. Until 1941, Ukrainian Jews' knowledge of German persecution had been restricted to those living in Nazi-occupied Western Ukraine. During the German occupation the Jews were driven into a helpless position, terrorized, deprived of all means of survival, and isolated. That is the reason why the German occupation authorities did not face major obstacles during the first wave of killings. This changed in 1942, especially during the ghetto raids beginning that summer. Jews tried to escape en masse into woods or to hide in cities and towns. During the ghetto liquidations even armed resistance occurred, first in western Volhynia, but in 1943 also in Galicia. However, only a small minority of the victims was able to survive by hiding in family camps in the woods, joining the partisans, or going into hiding elsewhere.

The preconditions for organized Jewish resistance were rather limited in Ukraine because there was little favorable terrain, such as woods. For the same reason, there was only a limited and late non-Jewish resistance movement. Jews were especially vulnerable to reprisals. While Ukraine's ethnic German population largely supported anti-Semitism, the general attitude of other non-Jews towards the Holocaust in Ukraine, especially of ethnic Ukrainians but also Poles and Russians, is still under debate. There existed a certain degree of anti-Semitism, especially in western Ukraine, whose population was radicalized as a result of the suffering it experienced under Soviet rule in 1939–41. But it also existed in the Donets Basin. According to German reports, denunciations of Jews were frequent, especially during the early period of the Nazi occupation. OUN groups propagated anti-Semitic stereotypes in 1941 and 1942, and the OUN officially took a different stand only in mid-1943. While Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic church spoke out against anti-Jewish violence, some bishops of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox church displayed a different attitude. The occupation authorities confiscated all valuables from the Jews, but certain non-German gentiles also profited by plundering Jews and especially by taking over their flats, furniture, clothes, and sometimes even their shops. On the other hand, other Ukrainians and Poles risked their lives to hide thousands of Jews, especially in the cities and towns. Many such gentile humanitarians were executed when they were caught. As of 2003, 1,984 persons from Ukraine have been honored as “Righteous among the Nations” by the Yad Vashem Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority in Jerusalem.

There is no doubt that the murder of the Jews was committed by the Third Reich and organized and carried out primarily by Germans and Austrians. Nevertheless, owing to a lack of personnel, these perpetrators of genocidal crimes relied heavily on indigenous auxiliaries. The German police had more than 120,000 members of the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police at its disposal; many of them participated in persecuting and murdering the Jewish minority, especially in 1942. The auxiliaries, predominantly attached to the German Order Police (Municipal Police and Gendarmerie), guarded ghettos; from autumn 1941 they took part in most of the killing actions as guards, sometimes even shot the victims, and had to search for Jews in hiding and deliver them to the German authorities. At least some of the auxiliary police troops, the Schutzmannschafts-Bataillone, participated in the killings. Ukrainian auxiliaries were the main target of criminal investigation after 1943–44. Probably several thousand of them were tried by Soviet courts and received severe punishment. Among the main criminals responsible for the Holocaust in general, however, only some two hundred Germans and Austrians faced justice in other countries.

The Jewish minority was the major victim of the German (and Romanian) occupation of Ukraine from 1941 to 1944. In addition, on Ukrainian soil 500,000 to 700,000 Soviet prisoners of war were starved to death or shot; tens of thousands of persons (eg, Communist Party and OUN functionaries or simply “partisan suspects”) considered political enemies were ruthlessly killed; an unknown number of non-Jewish city residents, probably several hundred thousand, died from deliberate undernourishment during the years 1941–43; and thousands of Ostarbeiter and other persons deported to work as slave laborers in Germany and Austria perished. (See Nazi war crimes in Ukraine.)

Public preservation of the memory of the Holocaust was limited in Soviet Ukraine only to a short period after the war. Thereafter it vanished almost completely from the official commemoration of the war; instead the Soviet myth of the “Great Patriotic War” concentrated on Communist resistance (see Soviet partisans in Ukraine, 1941–5) and almost completely neglected the Jewish identity of the war's myriad victims, referring to them only as “peaceful Soviet citizens.” Consequently their memory was preserved primarily by Holocaust survivors from Ukraine who became postwar refugees in North America, Israel, and Western Europe.

Only since the late 1980s have initially mostly governmental and then public efforts been made to memorialize this crime against humanity and integrate it into the history of independent Ukraine.

Dieter Pohl

[This article was submitted in February 2007. The bibliography below was updated by the editors in December 2008. For additional information, see the Web site of the Ukrainian Center for Holocaust Studies, http://holocaust.kiev.ua, which was established in Kyiv in 2002.]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Friedman, Philip. Roads to Extinction: Essays on the Holocaust, ed. Ada June Friedman (New York 1980)

Marrus, Michael R. (ed). The Nazi Holocaust: Historical Articles on the Destruction of European Jews (Westport, Conn. 1989)

Spector, Shmuel. The Holocaust of Volhynian Jews, 1941–1944 (Jerusalem 1990)

Dobroszycki, Lucjan, and Jeffrey S. Gurock (eds). The Holocaust in the Soviet Union: Studies and Sources on the Destruction of the Jews in Nazi-Occupied Territories of the USSR, 1941–1945 (Armonk, N.Y. 1993)

Friedman, Tuviah (ed). Report by SS-General Fritz Katzmann on the Killing of the Half Million Jews of Eastern Galicia: Documentary Collection (Haifa 1993)

Braham, Randolph L. (ed). Anti-Semitism and the Treatment of the Holocaust in Postcommunist Eastern Europe (New York 1994)

Pohl, Dieter. Nationalsozialistische Judenverfolgung in Ostgalizien, 1941–1944: Organisation und Durchführung eines staatlichen Massenverbrechens (Munich 1996)

Kruglov, A. I. Unichtozhenie evreev Ukrainy, 1941–1944: Khronika sobytii (Kharkiv 1997)

Ielisavets'kyi, S. Ia. (ed). Katastrofa i opir ukraïns'koho ievreistva (1941–1944): Narysy z istoriï Holokostu i oporu v Ukraïni (Kyiv 1999)

Dean, Martin. Collaboration in the Holocaust: Crimes of the Local Police in Belorussia and Ukraine, 1941–1944 (London 2000)

Kovba, Zhanna. Liudianist' u bezodni pekla: Povedinka mistsevoho naselennia Skhidnoï Halychyny v roky “ostatochnoho rozv’iazannia ievreis'koho pytannia” (Kyiv 1998; rev ed 2000)

Kruglov, A. I. (ed). Entsiklopediia Kholokosta: Evreiskaia entsiklopediia Ukrainy (Kyiv 2000)

Katzmann, Fritz. Rozwiązanie kwestii żydowskiej w Dystrykcie Galicja (Warsaw 2001)

Shmuel, S. and G. Wigoder (eds). The Encyclopedia of Jewish Life before and during the Holocaust, 3 vols (Jerusalem and New York 2001)

Kruglov, A. (ed). Sbornik dokumentov i materialov ob unichtozhenii natsistami evreev Ukrainy v 1941–1944 godakh (Kyiv 2002)

Redlich, Shimon. Together and Apart in Brzezany: Poles, Jews, and Ukrainians, 1919–1945 (Bloomington, Ind. 2002)

Tiaglyi, M. I. (ed). Kholokost v Krymu: Dokumental'nye svidetel'stva o genotside evreev Kryma v period natsistskoi okkupatsii Ukrainy, 1941–1944 (Simferopol 2002)

Langerbein, Helmut. Hitler’s Death Squads: The Logic of Mass Murder (College Station, Tex. 2003)

Berkhoff, Karel C. Harvest of Despair: Life and Death in Ukraine under Nazi Rule (Cambridge, Mass., 2004)

Hon, Maksym (ed). Holokost na Rivnenshchyni (dokumenty i materialy) (Zaporizhia 2004)

Mitsel', M. Evrei Ukrainy v 1943–1953 gg.: Ocherki dokumental'noi istorii (Kyiv 2004)

Kruglov, Alexander. The Losses Suffered by Ukrainian Jews in 1941–1944 (Kharkiv 2005)

Lower, Wendy. Nazi Empire-Building and the Holocaust in Ukraine (Chapel Hill 2005)

Navrots'ka, E., and Iu. Zeikan (eds). Bilyi kamin' z chornoï kativni: Holokost romiv Zakarpattia (Uzhhorod 2006)

Dietsch, Johan. Making Sense of Suffering: Holocaust and Holodomor in Ukrainian Historical Culture (Lund 2006)

Gesin, Michael. The Destruction of the Ukrainian Jewry during World War II (Lewiston, N.Y., 2006)

Rashkovetskii, M. (ed). Istoriia Kholokosta v Odesskom regione: Sbornik statei i dokumentov (Odesa 2006)

Zabarko, Boris (ed). Zhizn' i smert' v epokhu Kholokosta: Svidetel'stva i dokumenty, 3 vols (Kyiv 2006–2007)

Barkan, Elazar, Elizabeth A. Cole, and Kai Struve (eds). Shared History—Divided Memory: Jews and Others in Soviet-Occupied Poland, 1939–1941 (Leipzig 2007)

Rubenstein, Joshua, and Ilya Altman (eds). The Unknown Black Book: The Holocaust in the German-Occupied Soviet Territories (Bloomington, Ind. 2007)

Brandon, Ray, and Wendy Lower (eds). The Shoah in Ukraine: History, Testimony, Memorialization (Bloomington, Ind. 2008)

Desbois, Rev Patrick. The Holocaust by Bullets: A Priest’s Journey to Uncover the Truth behnid the Murder of 1.5 Million Jews (London and New York 2008)

.jpg)