Kotliarevsky, Ivan

Kotliarevsky, Ivan [Котляревський, Іван; Kotljarevs’kyj], b 9 September 1769 in Poltava, d 10 November 1838 in Poltava. Poet and playwright; the ‘founder’ of modern Ukrainian literature. After studying at the Poltava Theological Seminary (1780–9), he worked as a tutor at rural gentry estates, where he became acquainted with folk life and the peasant vernacular, and then served in the Russian army (1796–1808). In 1810 he became the trustee of an institution for the education of children of impoverished nobles. In 1812 he organized a Cossack cavalry regiment to fight Napoleon Bonaparte and served in it as a major (see Ukrainian regiments in 1812). He helped stage theatrical productions at the Poltava governor-general's residence and was the artistic director of the Poltava Free Theater (1812–21). From 1827 to 1835 he directed several philanthropic agencies.

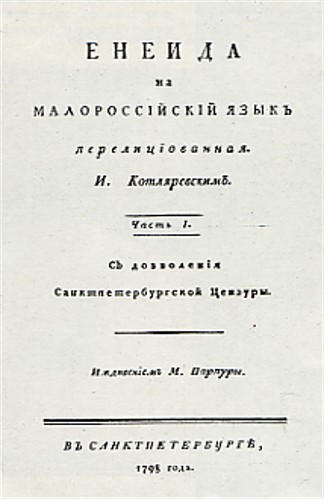

Kotliarevsky's greatest literary work is his travesty of Virgil's Aeneid, Eneïda, which he began writing in 1794. Publication of its first three parts in Saint Petersburg in 1798 was funded by Maksym Parpura. Part four appeared in 1809. Kotliarevsky finished parts five and six around 1820, but the first full edition of the work (with a glossary) was published only after his death, in Kharkiv in 1842. Eneïda was written in the tradition of several existing parodies of Virgil's epic, including those by P. Scarron, A. Blumauer, and N. Osipov and A. Kotelnitsky. Although the Osipov-Kotelnitsky travesty served as a model for Kotliarevsky's mock-heroic poem, the latter is, unlike the former, a completely original work and much better from an artistic point of view. In addition to the innovation of writing it in the Ukrainian vernacular, Kotliarevsky used a new verse form—a 10-line strophe of four-foot iambs with regular rhymes—instead of the then-popular syllabic verse.

Eneïda was written at a time when popular memory of the Cossack Hetmanate was still alive and the oppression of tsarist serfdom in Ukraine was at its height. Kotliarevsky's broad satire of the mores of the social estates during these two distinct ages, combined with the in-vogue use of ethnographic detail and with racy, colorful, colloquial Ukrainian, ensured his work's great popularity among his contemporaries. It spawned several imitations (by Petro Hulak-Artemovsky, Kostiantyn Dumytrashko, Pavlo Biletsky-Nosenko, and others) and began the process by which the Ukrainian vernacular acquired the status of a literary language, thereby supplanting the use of older, bookish linguistic forms.

Kotliarevsky's operetta Natalka Poltavka (Natalka from Poltava) and vaudeville Moskal’-charivnyk (The Muscovite-Sorcerer) were landmarks in the development of Ukrainian theater. Written ca 1819, they were first published in vols 1 (1838) and 2 (1841) of the almanac Ukrainskii sbornik edited by Izmail Sreznevsky. Both were written for and performed at the Poltava Free Theater; both, particularly the first, were responses to the caricatures of Ukrainian life in Prince Aleksandr Shakhovskoi's comedy Kazak-stikhotvorets (The Cossack Poetaster), which was also staged at the Poltava Theater. As a playwright, Kotliarevsky combined the intermede tradition with his knowledge of Ukrainian folkways and folklore.

Kotliarevsky's influence is evident not only in the works of his immediate successors (Hryhorii Kvitka-Osnovianenko, Taras Shevchenko, Yakiv Kukharenko, K. Topolia, Stepan Pysarevsky, and others), but also in the ethnographic plays of the second half of the 19th century and in Russian (the works of the ethnic Ukrainians Nikolai Gogol and Vasilii Narezhny) and Belarusian (the anonymous Eneida navyvarat [The Aeneid Travestied]) literature. In his use of genres and poetics he was more a Baroque-influenced Classicist than an incipient Romantic. His view of the world was guided by moral rather than by sociopolitical criteria, and his sympathy for the socially and nationally oppressed Ukrainian peasantry was subordinated to his loyalty to tsarist autocracy. Full editions of his works appeared in Kyiv in 1952–3 and 1969. The Kotliarevsky Museum was opened in Poltava in 1952.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Zhitetskii, P. ‘Eneida’ Kotliarevskogo i drevneishii spisok ee v sviazi s obzorom malorusskoi literatury XVIII v. (Kyiv 1900)

Zerov, M. Nove ukraïns’ke pys’menstvo (Kyiv 1924; Munich 1960)

Aizenshtok, Ia. I. Kotliarevs’kyi i ukraïns’ka literatura (Kyiv 1928)

Zalashko, A. (ed). I.P. Kotliarevs’kyi u krytytsi ta dokumentakh (Kyiv 1959)

Ivan Kotliarevs’kyi u dokumentakh, spohadakh, doslidzhenniakh (Kyiv 1969)

Kyryliuk, Ie. Zhyvi tradytsiï: Ivan Kotliarevs’kyi ta ukraïns’ka literatura (Kyiv 1969)

Moroz, M. Ivan Kotliarevs’kyi: Bibliohrafichnyi pokazhchyk (Kyiv 1969)

Čyževs’kyj, D. A History of Ukrainian Literature (From the 11th to the End of the 19th Century) (Littleton, Colo 1975)

Sverstiuk, Ie. ‘Ivan Kotliarevs’kyi Is Laughing,’ in his Clandestine Essays, trans and ed G.S.N. Luckyj (Cambridge, Mass 1976)

Iatsenko, M. Na rubezhi literaturnykh epokh: ‘Eneïda’ Kotliarevs’koho i khudozhnii prohres v ukraïns’kii literaturi (Kyiv 1977)

Pavlo Petrenko

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 2 (1988).]