Ceramics

Ceramics (кераміка; keramika). Objects made of natural clays or clays mixed with mineral additives and fired to a hardened state. Ceramics are used for both technical and artistic purposes and can be grouped in a number of categories: electrotechnical ceramics, terra-cotta (small clay objects), traditional pottery, and artistic ceramics (one of the decorative arts).

The ceramics made on the territory of Ukraine from the earliest times to the present reveal a highly developed artistic and technical culture, originality, and creativity. The development of ceramics has been facilitated by the existence of large deposits of various clays, particularly kaolin (china clay).

The history of Ukrainian ceramics begins in the Neolithic Period, with the ceramics of the Trypillia culture. Their high technical and artistic level equals that seen in artifacts of the Aegean culture. Also interesting are the ceramics made by various cults. The development of Ukrainian ceramics was also influenced by the ceramics of the Hellenic colonies on the Black Sea coast, beginning in the 8th and 7th century BC (see Ancient states on the northern Black Sea coast).

Ceramics of the so-called Slavic era, which began in the 2nd century AD, were more modest, and only in the Princely era (9th–13th century) did the production of ceramics achieve a high technical level and a variety of artistic forms, while growing into a large industry. Many forms of dishes were produced, as well as decorative, glazed tiles that were used for the floors of churches and palaces. The tiles of princely Halych in the 12th–13th century depicted griffons, peacocks, eagles, and doves in relief; they were cast with the use of carved wooden forms. Their characteristic feature is the joining of the Byzantine art and Romanesque style. After the Mongol period the potter's wheel was widely introduced, and its use finally supplanted the manual shaping of pottery. In the 14th and 15th century ceramic manufacturing declined, and a revival began both on the technical and artistic levels only with the appearance of trade guilds (at the end of the 15th century). In the 17th and 18th centuries the making of ceramics flourished in Ukraine. Ukrainian artists and craftsmen boldly transformed the lavish styles of the baroque and created an original decorative style with ornamental motifs and a tasteful harmony of colors. In addition to kitchenware and tableware, an architectural element—the stove—was developed. In the 18th century enameled tiles were produced in almost all ceramic-producing centers in Ukraine, particularly in the Chernihiv region, where small manufacturing factories were located in Chernihiv itself and in Tulyholove, Novhorod-Siverskyi, Hlukhiv, and Baturyn.

The technology of ceramics for construction purposes became highly developed in the 18th century: bricks, ridge tiles, ornamental slabs and tiles, attractive ceramic shields decorated with colored glazes, and fantastic rosettes symbolizing the sun were produced. At this time the manufacture of faience and porcelain developed in a number of centers, including Mezhyhiria near Kyiv (see Mezhyhiria Faience Factory), Korets and Baranivka in Volhynia, Tomashiv (Tomaszów Lubelski) in the Kholm region, and Volokytno in the Chernihiv region. Hand-shaped and dried dishes were painted by potters (after a first firing in the kiln) with white, yellow, and brown clays or a combination of colors, which melted in the second firing. Green color was obtained from burnt copper filings, and various types of ocher provided different shades of red. Effective colored glazes were already being used in the Renaissance and baroque periods, and by the end of the 18th century potters were using so-called granular glazes—which included in the glaze colored coarse granules of metal oxides that, in firing, melted with the glaze and gave a lustrous (opallike) blue, green, or violet shade to the objects (this method is still in use in the Kharkiv region). Some household pottery was covered with a light green lead glaze, which has been replaced today by various artistic enamel glazes. Ornamentation was scratched out on the surface of dried, unfired dishes with a stylus, and painting was usually done with a quill.

The forms of these ceramic dishes and pots bring to mind the anthropomorphism of Grecian vases, yet they display a specific originality. Their stylistic peculiarities were based on the local characteristics and traditions of folk art. Ukrainian artists, using the so-called ribbon technique on the potter's wheel, created various types of kitchenware and tableware: soup bowls, plates, cups, pots, mixing bowls, pitchers, jugs, small vessels, flasks, jugs in the form of wheels, and also candlesticks, candelabrums, and terra-cotta lamps. In the 18th century an important center of ceramic manufacturing was the pottery village of the Zaporozhian Sich. It produced a rich variety of surprisingly skillfully made folk terra-cotta playthings, such as small whistles, and particularly figures of the animal world: cats, rams, cocks, etc. These small ceramic sculptures were often presented in a humorous fashion and are true masterpieces.

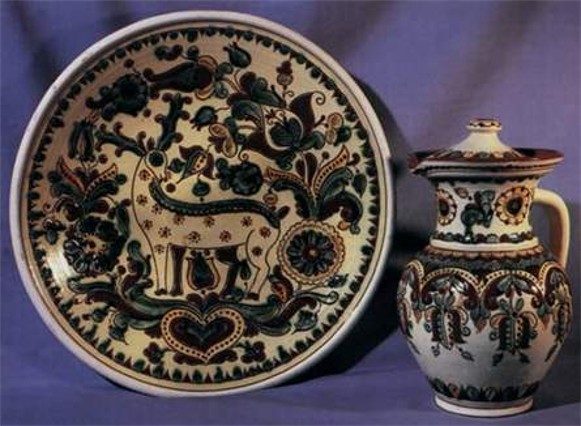

The ornamentation of Ukrainian ceramics is well thought out. The decorative elements used are similar to those that appear in other forms of folk art. Some of the oldest elements used are geometric motifs such as dots, straight lines, wavy lines, broken lines, crosses, meanders, and combinations of flat geometric figures such as squares, triangles, and circles—all logically connected with the form of the individual piece. The floral ornamentation and natural patterns taken from the immediate surroundings, stylized into decorative motifs, contain a surprisingly wide range of artistic interpretations, ranging from naturalistic strokes to fantastical depictions. The same applies to the artistic, ornamental rendering of the human figure and various animals.

The territorial distribution of ceramic production depended on the deposits of suitable kaolin clay. The first centers of ceramic manufacture in Ukraine were the village of Dybyntsi in the Kyiv region, an ancient pottery center with the marvelous dynamism of the authentic Ukrainian baroque of the 18th century; the village of Vasylkiv, a rich center of ceramic ornamentation with a potters' artel, which later became a majolica factory famous for its production of souvenirs; and the village of Obukhiv.

The village of Holovkivka in the Cherkasy region is a well-known center, famous particularly for its individual style of decoration known as fliandrivka (a peculiarly Ukrainian technique of painting on unbaked clay). In the old Cossack town of Opishnia in the Poltava region, glazes were rarely used, but the pottery produced there was of very fine quality and decorated with geometric motifs. From the second half of the 19th century this creative decoration gave way to a form of fliandrivka, carefully executed with restraint and great artistic taste. Today Opishnia is a center producing ceramic toys and small ceramic sculptures. Well-known modern ceramics artists from Opishnia include Oleksandra Seliuchenko, N. Poshyvailo, and M. Didenko. One of the late 19th-century masters of ceramic figurative sculpture in Opishnia was O. Nochovnyk. Great traditions continue to develop in the work of modern artists such as I. Bilyk, H. Kyriachok, V. and P. Omelchenko, and T. and V. Demchenko.

Other important ceramics centers in the Poltava region are the cities of Zinkiv (Poltava oblast) and Myrhorod. In the Chernihiv region Ichnia was renowned throughout the 19th century for its production of original decorative tiles with an almost total exclusion of the color red, but with a technically brilliant facility of design. In the Kharkiv region, ceramics produced in the villages of Nova Vodolaha and Tonivka were known for their brilliant colors, dominated by bright yellow, orange, and green, their balanced slender compositions, and the widespread application of ancient geometric elements. In the Vinnytsia region the ceramic guild in the city of Bar was famous as early as the 15th century. Besides ceramic ware for everyday use, a variety of terra-cotta human figurines and anthropomorphic vases were produced there.

Considerable originality and expert workmanship are revealed in the ware of a more folk character. In Transcarpathia the centers of ceramic production include Uzhhorod, the village of Vilkhivka (known for its decoration of ceramics by the Sgraffito technique, with convex objects appearing on a dark background), and Dubovenka. In the Ternopil region the centers include the villages of Zalistsi and Tovste (renowned in the past for beautiful fliandrivka ware); and the city of Berezhany (known for pitchers, flasks, plates, and bowls that were mostly covered with a white glaze ornamented with fine fliandrivka bands). In the Lviv region the cities of Sokal, Yavoriv, Komarno, and Sambir and the village of Potelych are among the main ceramics centers; their ornamentation is unique in content as well as composition.

Ceramics production developed intensively in the Hutsul region and in Pokutia in such well-known centers as Kosiv, Pistyn, Kuty, Halych, and Kolomyia. Kosiv and adjacent Pistyn, as early as the 18th century, were known for their painted bowls, sculptured tiles, and elegant candlesticks with ornamental and figurative scenes. Kosiv was also famous for its painted tile stoves with distinctly original forms. During the 19th century Kosiv craftsmen created over 400 tile stoves, some of which can still be seen today in the surrounding villages. (Most of them are now in museums.) Hutsul potters knew intuitively the rules of decorative art in relation to the character of the object for which the decoration was intended. Distinct contrasts of a few colors are characteristic of the pictures on dishes and hand-shaped objects: brown clay, dark-brown drawing, and free brushstrokes of green and golden glaze, which do not always coincide with the contours of the picture; this apparent carelessness or imperfection gives the decoration pictorial spontaneity and lightness. In figurative compositions the ceramists of Kosiv and Pistyn use great detail and uniform lines and colors. Today these centers produce mostly souvenirs, decorative plates, flower vases, pitchers, flowerpots, statuettes, flasks, casks, etc.

Among the most prominent Hutsul ceramists at the end of the 19th century were P. Baraniuk, Oleksa Bakhmatiuk, and M. Koshchuk. The most prominent modern craftsmen include P. Lazarovych, Y. Tabakharniuk, and the Voloshchuk, Koshak, Tsvilyk, and Tymiak families.

The development of ceramics was aided by trade schools. In Western Ukraine the first school was founded in 1874 in Kolomyia, while in Lviv, Uzhhorod, and Khust there were pottery departments in art schools. A native of Myrhorod, V. Trebushny, directed the ceramics workshop of the Cracow Academy of Arts from 1928 to 1939. In the Myrhorod school artists such as Vasyl H. Krychevsky, Opanas Slastion, Osyp Biloskursky, H. Levynsky, and Serhii Lytvynenko were teachers. Today much work is being done to develop and introduce new ceramics materials—varied glazes, enamels, and pigments—at the experimental workshop of ceramic art of the Kyiv Scientific Research Institute of Experimental Planning. Many artists have taken advantage of this research, including Dmytro Holovko, whose works are of a decorative-monumental nature and form an effective integral part of both public and residential interiors.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Shukhevych, V. Hutsul’shchyna (Lviv 1901–8)

Pchilka, O. Maliuvannia na ukraïns’kykh myskakh (Kyiv 1910)

Ionov, N. Goncharskii promysel Kievskoi gubernii (Kyiv 1912)

Mykhailiv, Iu. Shliakhy ukraïns’koï keramiky (Kyiv 1926)

Fride, M. Forma i ornament posudu z Podillia (Kyiv 1928)

Sichyns’kyi, V. Ukraïns’ke uzhytkove mystetstvo (Prague 1944)

Manucharova, N. Khudozhni promysly Ukraïns’koï RSR (Kyiv 1953)

Lashchuk, Iu. Hutsul’s’ka keramika (Kyiv 1955)

Mateiko, K. Narodna keramika zakhidnykh oblastei Ukraïns’koï RSR XIX–XX st. (Kyiv 1959)

Lashchuk, Iu. Zakarpats’ka narodna keramika (Uzhhorod 1960)

Pasternak, Ia. Arkheolohiia Ukraïny (Toronto 1961)

Hurhula, I. Narodne mystetstvo zakhidnykh oblastei Ukraïny (Kyiv 1966)

Danchenko, L. Narodna keramika Naddniprianshchyny (Kyiv 1969)

Lashchuk, Iu. Narysy z istoriï ukraïns’koho dekoratyvno-prykladnoho mystetstva (Lviv 1969)

Lashchuk, Iu. Ukraïns’ke narodne mystetstvo (keramika i sklo) (Kyiv 1974)

Hoshko, Iu. Narodni khudozhni promysly Ukraïny (Kyiv 1979)

Shcherbakivs’kyi, V. Mystetstvo ukraïns’koï khaty (Rome 1980)

Poshyvailo, O. Etnohrafiia ukraïns’koho honcharstva: Livoberezhna Ukraïna (Kyiv 1993)

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 1 (1984).]

.jpg)