Moldavia

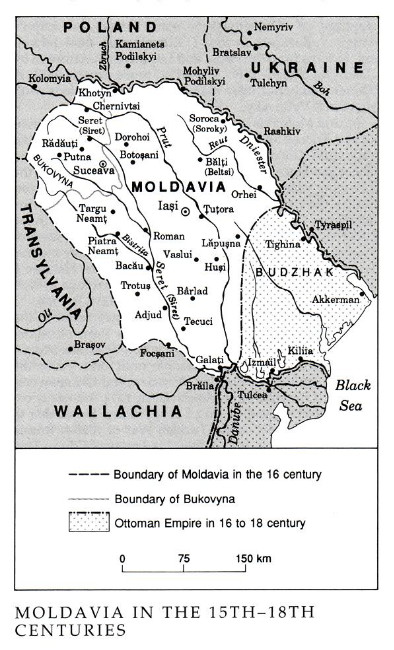

Moldavia [Romanian: Moldova; Ukrainian: Молдавія, Волощина; Moldaviia, Voloshchyna, from волохи; volokhy ‘Vlachs’]. A region (approximate area, 90,000 sq km) bordering on southwestern Ukraine. Its natural boundaries are the Carpathian Mountains to the west, the Dnister River to the east, and the Black Sea to the south. Named after the Moldova River, in the 14th century it became a Vlach principality, which ruled Bukovyna until 1774 and Bessarabia until 1812. Later the principality was reduced to the territory between the Carpathians and the Prut River, which is now part of Romania. In 1859 it was united with Wallachia to form the state of Romania. After the Second World War Bessarabia became the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic, and in 1991, Moldova.

In prehistoric times Moldavia was inhabited by Scythians and Thracian tribes (Getae, Dacians), who established an independent state there in the 1st century BC. From 106 to 273 AD southern Moldavia was part of the Roman Empire, which built Trajan’s Walls there. From the 3rd century on it was invaded by many nomadic peoples, including the Goths, Huns, Avars, Volga Bulgars, Magyars, Pechenegs, Cumans, and Tatars. From the 4th century on, particularly from the 6th, the East Slavic Antes settled there. In the 9th and 10th centuries Moldavia was colonized by the proto-Ukrainian Tivertsians and Ulychians, who founded the towns of Peresichen, Tehyn (now Bendery or Tighina), and Bilhorod (now Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi).

In the 10th century the territory of Moldavia came under the domination of Kyivan Rus’, and from 1200 to 1340 it was ruled by the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia. Important trade routes from Galicia to the Black Sea passed through Moldavia, and Galician merchants founded the town of Malyi Halych (now Galaţi) there. In the 12th and early 13th centuries a separate principality populated by fugitives from Galicia-Volhynia called Berladnyky (named after the Moldavian town of Berlad [Bîrlad]) existed in southern Moldavia. Its most notable ruler was Ivan Rostyslavych Berladnyk.

After the Tatar invasion of 1241 Galician influence in Moldavia waned, contacts with the Eastern Slavs beyond the Carpathian Mountains diminished, and Vlachs from Wallachia began settling there. In 1352 King Louis I of Hungary expelled the Tatars from Moldavia and installed the Vlach Dragoş as its voivode (military governor). Under Dragoş the influx of Vlachs from Transylvania and the Maramureş region intensified. In 1359 the new voivode, Bogdan, overthrew Hungarian rule and founded an independent Moldavian principality dominated by boyars and the Orthodox church. The capital was Suceava. In that period the Lithuanian-Ruthenian prince Yurii Koriiatovych, the nephew of the Lithuanian grand duke Algirdas, served briefly as a Moldavian voivode. In 1387 Moldavia became a Polish vassal state. In the late 14th century it extended its borders to the Carpathian Mountains, the Dnister River, the Danube River, and the Black Sea and occupied the northern part of Shypyntsi land (Bukovyna). In 1456 it became an autonomous tribute-paying vassal state of the Ottoman Empire.

Moldavia prospered during the reigns of its voivodes Alexander the Good (1400–32) and Stephan III the Great (1457–1504). Under Alexander the Patriarch of Constantinople recognized the separate Moldavian metropoly in Suceava (1401), and commercial ties with Lviv were secured, whereby Moldavian merchants were granted privileges. Stephan married Yevdokiia, the daughter of the Kyivan prince Olelko Volodymyrovych. He repulsed the Hungarians in 1467, the Turks in 1475–6, and the Poles in 1497, after which Moldavia enjoyed full independence until 1538. Stephan and his successors Bogdan III and Peter Rareş (1527–46) often invaded Pokutia and sought to annex it. During the Polish-Moldavian wars in Pokutia, Ukrainian and Moldavian peasants took part in the Mukha rebellion (1490–2), and many Galician Ukrainian fugitives settled in Moldavia.

After Moldavia was forced to accept Turkish suzerainty in 1538, the Zaporozhian Cossacks assisted the Moldavians in their struggle against Turkey and intervened in their internal power struggles. In 1541 a Zaporozhian force waged a campaign against Turkish-Tatar garrisons on the lower Dnister River. In 1563 Prince Dmytro Vyshnevetsky led two Zaporozhian campaigns against the Turks in Moldavia. In 1574 a force of 1,200 Cossacks led by Otaman I. Svirchevsky took part in the anti-Turkish rebellion led by the hospodar John the Terrible. In 1577 Otaman Ivan Pidkova briefly occupied the Moldavian throne. In 1583 the Cossacks attacked Turkish garrisons in Moldavia and destroyed the fortress in Bendery. In 1594–5 Severyn Nalyvaiko and Hryhorii Loboda led Cossack raids into Moldavia to help anti-Turkish insurgents. In 1600 a force of 7,000 Cossacks fought for Michael the Brave of Wallachia during his war against the Turks in Moldavia and Transylvania. During the Polish-Turkish War of 1620–1 Cossack units led by Mykhailo Khmelnytsky and Bohdan Khmelnytsky were defeated by the Turks at the Battle of Cecora in Moldavia, but the forces of Hetman Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny played a key role in the Polish victory at the Battle of Khotyn. In 1635 Zaporozhians led by Ivan Sulyma plundered the Turkish-held Moldavian port of Kiliia.

Moldavia played an important part in Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky’s Cossack-Polish War of 1648–57. Because the Moldavian hospodar Vasile Lupu was an ally of Poland, Khmelnytsky led his army against Moldavia in 1650 and forced Lupu into an alliance. After the Cossack defeat at the Battle of Berestechko in 1651, Lupu broke away, but he was forced back into the alliance by a second Cossack offensive against Moldavia, in 1652. The alliance was sealed by the marriage of Khmelnytsky’s son, Tymish Khmelnytsky, to Lupu’s daughter, Roksana Lupu. In 1653 T. Khmelnytsky died defending Suceava from the Poles (see Battle of Suceava), and Lupu was overthrown by Gheorghe Ştefan, who signed a peace treaty with B. Khmelnytsky and later maintained good relations with Hetman Ivan Vyhovsky.

In 1672 Moldavia was allied with Hetman Petro Doroshenko and Turkey against Poland. In 1681 the Turkish sultan appointed Gheorghe Duca ‘hospodar of Ukraine,’ but Gheorghe Duca ruled only Moldavia and only until the following year. At that time many Moldavians began settling in the Ukrainian lands between the Dnister River and the Boh River. Cossack units led by Stepan Kunytsky fought in the Polish army that ended the Turkish-Moldavian siege of Vienna in 1683, and they continued the offensive against Turkey in Hungary, Wallachia, and Moldavia. Hetman Ivan Mazepa and his successor, Pylyp Orlyk, sought refuge in Moldavia after their defeat at the Battle of Poltava in 1709.

After the anti-Ottoman military alliance between the Moldavian prince D. Cantemir and Tsar Peter I was defeated in 1711, Moldavia was governed by Greek Phanariots appointed by Constantinople until 1821. From the late 18th century the Russian, Austrian, and Ottoman empires vied for control of Moldavia. In 1774 Austria occupied Bukovyna, and in 1812 Turkey ceded Bessarabia to Russia. During the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–9 Russia occupied Moldavia, and in the 1829 Treaty of Edirne Turkey recognized Moldavia’s autonomy under Russian tutelage. In 1859 the principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia elected A. Cuza as their joint ruler, and their union as the country of Romania was formally proclaimed on 23 December 1861.

Ukrainians and Moldavians have shared a common history (to the 14th century) and the Byzantine wellspring of culture and Orthodox religion. Ukrainian villages have existed in Moldavia for centuries. The medieval Moldavian state and society were similar to those of Kyivan Rus’ and the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia, and Ukrainian was the official language of the Moldavian church and state (see Moldavian charters). Not until Iaşi became the new capital of Moldavia in 1564 did Romanian begin supplanting Ukrainian as the official language. The process was completed in the mid-17th century.

Ties between the Moldavian and Ukrainian churches were close. Under Voivode Peter I (1373–7) a Moldavian episcopate subordinated to Halych metropoly was established. Metropolitan Gregory Tsamblak of Kyiv contributed to the cultural development of Moldavia in the early 15th century. The Lviv Dormition Brotherhood, the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood School and the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood Press received ongoing assistance from Moldavian hospodars and boyars from the mid-16th to the late 17th century, and the Moldavian hospodars A. Lăpuşneanu and I. and S. Movilă helped fund the construction of the Dormition Church in Lviv. The Lviv Dormition Brotherhood School trained Moldavian leaders, including the chronicler G. Ureche and Metropolitan Dositheus.

The son of S. Movilă, Petro Mohyla, became the most outstanding metropolitan of Kyiv, and the famous college he founded in Kyiv (see Kyivan Mohyla Academy) was attended by Moldavian students. The college’s teachers Sofronii Pochasky and I. Yevlevych founded a similar Latin-Slavonic school in Iaşi in 1640, and Ukrainian printers founded a press there in 1641. Moldavian writers had their works printed in Lviv, Univ, Krekhiv, and Maniava. The Moldavian metropolitans Varlaam (1632–53) and Dositheus (1671–86, who was born in Lviv) translated church books from Ukrainian into Romanian. The influence of Ukrainian writers, such as Zakhariia Kopystensky, Meletii Smotrytsky, P. Mohyla, Pamva Berynda, Innokentii Gizel, Lazar Baranovych, Ioanikii Galiatovsky, and Paisii Velychkovsky, on Moldavian culture was considerable, and the Ukrainian towns of Kyiv, Lviv, Kamianets-Podilskyi, Univ, Zhovkva, and Bar had a cultural impact on Moldavia.

Because the trade route linking western Ukraine with Constantinople and the Near East passed through Moldavia, Moldavia had close economic ties with western Ukrainian cities. Those ties became stronger after Alexander the Good conferred special privileges on Lviv’s merchants in 1408 but were weakened after Turkish control over Moldavia increased. In the 18th century Ukraine and Moldavia were close trading partners.

Valuable information about Ukrainian-Moldavian relations from 1359 to 1743 can be found in the Moldavian chronicles of G. Ureche, M. and N. Costin, and I. Neculce.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Korduba, M. ‘Moldavs'ko-pol's'ka hranytsia na Pokuttiu do smerty Stefana Velykoho,’ Zbirnyk NTSh (Lviv 1906)

Nistor, I. ‘Contribuţii la relaţiunile dintre Moldova şi Ucraina în veacul al XVII-lea,’ Academia Română, Memoriile şecţiunii istorice, ser 3, vol 13 (1932–3)

Zhukovs'kyi, A. ‘Istoriia Bukovyny,’ in Bukovyna: Ïï mynule i suchasne, ed D. Kvitkovs'kyi, T. Bryndzan, and A. Zhukovs'kyi (Paris 1956)

Dan, M. Ştiri privitoare la istoria Ţărilor Romîne in cronicele ucrainene: Studii şi materiale de istorie medie, vol 2 (Bucharest 1957)

Sergievskii, M. Moldavo-slavianskie etiudy (Moscow 1959)

Mokhov, N. Ocherki istorii moldavsko-russko-ukrainskikh sviazei (s drevneishikh vremen do nachala XIX v.) (Kishinev 1961)

Mokhov, N.; Stratievskii, K. Rol' russkogo i ukrainskogo narodov v istoricheskikh sud'bakh Moldavii (Kishinev 1963)

Romanets', O. Dzherela braterstva: Bohdan P. Khashdeu i skhidnoromans'ko-ukraïns'ki vzaiemyny (Lviv 1971)

Ukraina i Moldaviia (Moscow 1972)

Joukovsky, A. ‘Les relations culturelles entre l’Ukraine et la Moldavie au XVIIe siècle,’ VIIe Congrès International des Slavistes: Varsovie, 21–27.8.1973 (Paris 1973)

Zelenchuk, V. Naselenie Moldavii (Demograficheskie protsessy i etnicheskii sostav) (Kishinev 1973)

Byrnia, P. Moldavskii srednevekovyi gorod v Dnestrovsko-Prutskom mezhdurech'e (XV–nachalo XVI v.) (Kishinev 1984)

Spinei, V. Moldavia in the 11th–14th Centuries (Bucharest 1986)

Dragnev, D.; et al (eds). Ocherki vneshnepoliticheskoi istorii Moldavskogo kniazhestva (posledniaia tret' XIV–nachalo XIX v.) (Kishinev 1987)

Arkadii Zhukovsky

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 3 (1993).]