Embroidery

Embroidery (вишивка, вишивання; vyshyvka, vyshyvannia).

History. Archeological discoveries in Ukraine indicate that embroidery has existed there since prehistoric times. Embroideries are found on drawings and on the oldest pieces of extant cloth (eg, the veil from the Church of the Tithes, destroyed in 1240).

Cloth embroidery was first inspired by faith in the power of protective symbols and later by esthetic motives. Symbolic designs were incorporated into the woven cloth by means of a weaving shuttle or a needle. These symbols formed the basis of ornamentation for both cloth and Easter eggs. Most of the symbols came from Asia. As a result of migrations, wars, and trade, they penetrated the Dnipro River Valley and the neighboring areas. In historical times they were transformed into more complicated patterns and modified by Byzantine influence (see Byzantine art). Under this influence a new branch of embroidery—church embroidery, which required imported materials and a more complicated technique—was developed.

In the course of time and under the influence of new artistic styles, folk embroidery and church embroidery became more differentiated. Centers of church embroidery developed in the monasteries, while certain cities (Kyiv, Lviv, Brody) became centers for the embroidery trade (haftiarstvo), which produced cloth for the Cossack starshyna and the nobility. The later artistic styles did not influence folk embroidery as much. Embroidery remained popular and developed as techniques and materials were perfected. Folk art specialists found that at the end of the 19th century it was flourishing in three fields—in the church, in folk customs, and for clothing.

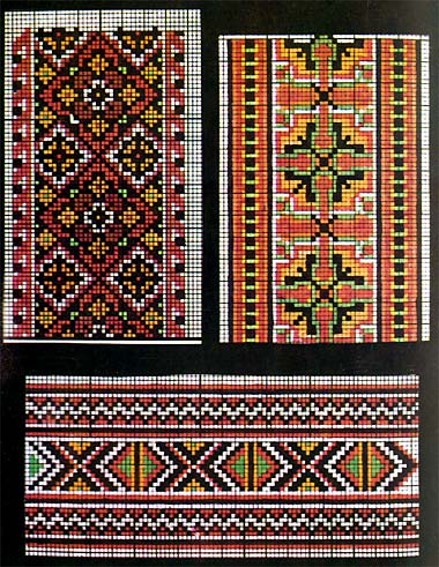

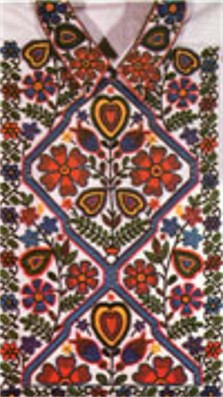

Ornamentation. Ukraine can be divided into three regions in terms of embroidery (as well as Easter egg) ornamentation: (1) the country's inaccessible areas, such as Polisia in the north and the Hutsul region in the Carpathian Mountains, where strict geometric patterns have been preserved; (2) central and eastern Ukraine, from the Buh River along the Dnipro River to the Black Sea, where floral designs predominate; and (3) the remaining areas (Volhynia, central Galicia, the Boiko region, and Poltava region), where floral motifs, when they occur, are strongly geometric in their interpretation.

Color was related to the embroidery pattern. Even in the case of complicated and varied designs, colors are limited to one or two, such as black and red. The finest examples are found in Polisia, where the embroideries are primarily red with a slight admixture of black. The same can be said of the embroideries of the Lemko region and Podilia. The geometric patterns of the Hutsul region and Bukovyna, however, are multicolored. At times floral motifs appear in a greater number of colors, such as black, red, and yellow. They differ greatly in form and reflect various artistic styles, whereas the geometric patterns still reflect the old symbols. Animal motifs are rarely encountered.

Among the neighboring peoples a rich geometric ornamentation can be found in central and eastern Russia, in Belarus, and in Romania. Realistic floral designs are developed among the Poles, Slovaks, and Hungarians.

Application. Embroidery designs are used mostly on clothing. A traditional form of embroidery is used for the shirt (for both men and women). The basic part of the design on a woman's shirt is placed on the upper sleeve just below the shoulder. This is an elongated design, 10–15 cm in breadth, called the polyk or ustavka. In some areas another strip is added under it, which is called the pidpolichchia or morshchynka. The lower length of the sleeve may also be embroidered. Other parts of the shirt—such as the collar, the front, the cuffs, and the bottom hem—have narrower bands of embroidery, which complement or harmonize with the main motif on the sleeve.

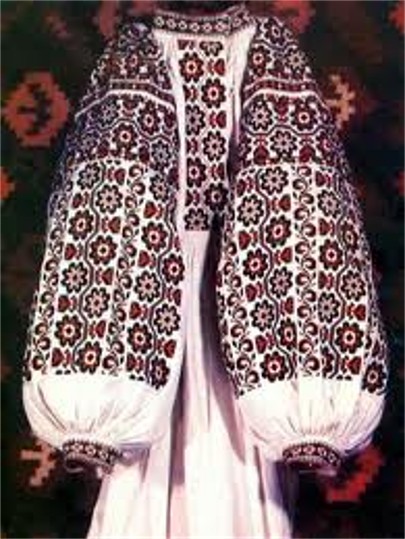

Shirts are beautifully embroidered throughout Ukraine, but other parts of the traditional costume are embroidered only in certain regions (eg, skirts among the Boikos, aprons in Polisia). The head covering of a married woman is simply, but meticulously, decorated. In Polisia this decoration is a narrow band that frames the face; in Pokutia it takes the form of broad, colored bands (zabory) woven into the ends of the headscarf, which hang down the back. The best-developed decorations are those on kerchiefs, in the form of large flowered motifs (eg, in the Yavoriv area and Lemko region). Other pieces of clothing also have embroidered decorations. Sleeveless jackets have intricate motifs of branches and flowers, and outer garments are decorated with various finishing stitches. Sheepskin jackets (kozhukhy) also have very intricate ornamentation.

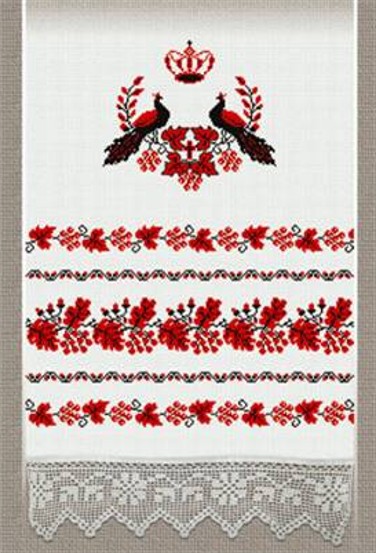

Special significance is attached to the embroidery on rushnyky (towels) and kerchiefs used in folk customs and rites. The ancient, symbolic signs are rarely found today; they have been replaced by floral designs extending along both sides of the rushnyk. Embroidered rushnyky were used in folk rites, particularly for weddings and for decorating holy icons. Embroidered kerchiefs were used in funerals for covering the face of the deceased.

Ukraine's neighbors use embroidery differently. All use a shirt that is more or less carefully decorated. In Russia the poneva—a wraparound garment—is decorated. Everywhere great attention is lavished on the head covering (Russia, Poland, Slovakia, Hungary), but only the Romanian style of head covering can rival the Ukrainian in its classic simplicity.

Techniques of embroidery

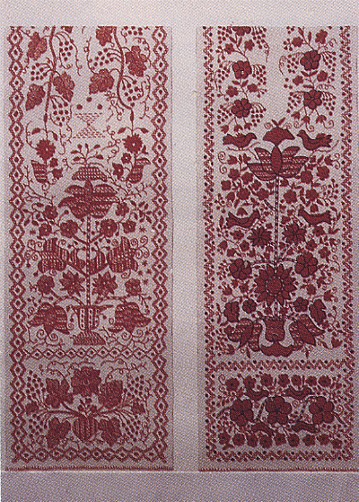

Solid stitches. The oldest technique of Ukrainian embroidery is the nyz, nyzia, or zanyzuvannia. This is done with red or black thread along the warp (the lengthwise threads) of the linen. The embroiderer works on the reverse side of the cloth and thus makes a negative pattern. The design is developed by advancing thread by thread in a progressive pattern. The threads of the cloth that are thus covered are always odd in number (1, 3, or 5). In theory the technique is simple, but in practice the person who has not done it since childhood can rarely accomplish it proficiently.

This method of embroidery—from the reverse side—can be employed only with geometric motifs which are formed by the crossing and breaking of lines. The motifs thus developed have a symbolic meaning and are regarded as having protective powers.

Related to this stitch is the zavolikannia or pidbyrannia (running stitch). This is not as well preserved as the nyz. While the nyz is usually done in black thread, more rarely in red, the zavolikannia is almost exclusively done in red with a very small mixture of black or blue. While the nyz is worked along the warp, the zavolikannia is done along the woof. The embroiderer advances in double or triple steps. While the steps in the pattern of the nyz are almost imperceptible, they are much clearer in the zavolikannia.

Such stitches are also found among Ukraine's neighbors. They are used in the central and eastern provinces of Russia, throughout Belarus, and in Romania, Bulgaria, and Serbia. However, they are not as widespread as in Ukraine, where they have been preserved in certain areas (Polisia, Hutsul region, Podilia).

The second most widespread technique of embroidery in Ukraine is the lyshtva (leafing stitch), a two-sided, counted satin stitch that makes the design appear almost the same on both sides of the cloth. As the unit for determining the count, the chysnytsia (ie, three threads, but even more can be included) is used. Embroideries done in lyshtva usually consist of stylized leaves or flowers in the form of geometric figures, or true geometric designs. In using this stitch the craftspeople at one time employed only white threads or unbleached threads on white linen. Later the linen threads were dyed in oak bark (light brown) or in ashes (gray). The embroidery thread must be heavier than the thread of the cloth. Lyshtva stitching is often used with openwork embroidery. This stitch, in various forms, is also found in Russia and in the Balkans, especially in those areas where geometric patterns predominate.

The most popular method of embroidery today is the cross-stitch. It is of more recent origin but has penetrated into the most remote areas because it made possible, to a large degree, the transition from geometric to floral motifs. The Ukrainian embroiderer has shown great care in the use of the cross-stitch, which easily permits the creation of personal designs. The cross-stitch has become widespread among all European peoples and in Ukrainian embroidery has replaced other, ancient techniques.

The most intricate stitches are those used for the headcloths in Galicia and for rushnyky in the Dnipro River region. The most important feature of these stitches is that they allow preliminary outlines of the designs, which are later filled with other stitches. Both the outline and the filling stitches are duplicated exactly on the front and reverse sides.

Openwork stitches. These are of three principal types: merezhka (cut-and-drawn work), stiahuvannia (drawnwork), and vyrizuvannia (cutwork).

In Ukrainian, unlike Russian, merezhka the threads are drawn crosswise only, and never lengthwise. The design is embroidered on the remaining lengthwise threads. Stiahuvannia is executed by drawing the lengthwise and crosswise strands into square or circular designs. In vyrizuvannia, which has developed in various parts of Ukraine (Poltava region, Polisia, Pokutia), first the contours of the cutwork sections (square or circular) are overcast in various prescribed ways, then the centers are cut out and the filling in is completed. The overcasting and filling are done usually with white or unbleached thread, and only rarely with brown or gray. Cutwork finishing is always used in conjunction with the lyshtva.

Threads. Originally the embroidery thread was the same linen thread used in weaving the cloth. So that it would be more durable, it was coated with wax or soot, which made it yellow or gray. Later the art of dyeing threads with plant dyes was discovered. More recently commercially manufactured threads have been introduced. Most of these are of colored cotton, but sometimes wool or silk threads are made. In southern Ukraine embroideries are also executed with metallic threads (gold and silver).

Embroidery production. Embroidering was done in the village by specialists in the art who worked for pay. These were talented persons who created their own patterns. Others also embroidered but copied the designs of the professionals.

At the end of the 19th century students of folk art saw the need for commercializing this field. The first steps in this direction were taken by the Poltava zemstvo, which founded several embroidery shops.

After the First World War efforts to revive the commercial production of embroidery were intensified. These steps were taken by the co-operatives and the state administration in Soviet Ukraine and by cultural and economic institutions in Western Ukraine. In the Ukrainian SSR these efforts attracted persons of significant artistic talent. Beginning in 1934, workshops for Ukrainian folk art were opened with the intention of exporting the products. The chief centers for the production of embroidery were Kamianets-Podilskyi oblast, Vinnytsia oblast, Zhytomyr oblast, Kyiv oblast, Chernihiv oblast, Poltava oblast, Kharkiv oblast, Odesa oblast, and Dnipropetrovsk oblast; in 1940 there were 109 artels employing 54,000 workers. In Western Ukraine production was concentrated in co-operatives: Ukrainske Narodnie Mystetstvo in Lviv; Hutsulske Mystetstvo in Kosiv; and the Women's Hromada in Bukovyna in Chernivtsi. All of these groups had their work exported; most of it was labeled Soviet or Polish.

As often happens in the transition from individual work to mass production, the quality of folk embroidery declined. Production methods were often inferior, and much harm was also done by the use of carelessly printed patterns.

Church embroidery. Church embroidery had quite a different character than that of folk embroidery. While the stitches of the latter were counted by strands (chysnytsi), church embroidery was done only by copying a free design.

Albs, chasubles, stoles, and veils were embroidered. The albs were embroidered usually on linen cloth in a broad band. The design was composed of a continuous motif, bordered on both sides by a chain stitch; above and below scattered flowers were embroidered. The embroidery thread used was a twisted silk of a dark red or dark green color combined with gold or silver thread. The stitches used on the albs were either the Poltava or old Kyiv types. Both resulted in heavy embroideries, covering large expanses. Often designs from rushnyky were used on the albs; then the thread used was red cotton. The church chasubles, stoles, and veils were embroidered with gold or silver thread. The technique of embroidering with gold was known by only a few people. Factory-made brocade later replaced church embroidery. Under the Soviet regime the art of church embroidery almost completely disappeared.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Wierzbicki, L. Wzory przemyslu domowego: Hafty włościan na Rusi (Lviv 1887)

Samokysh M.; Vasyl’kivs’kyi, S. Motyvy ukraïns’koho ornamentu (Kharkiv 1902)

Kolbenheyer, E. Motive der hausindustriellen Stickerei in der Bukowina (Vienna 1913)

Bilets’ka, V. ‘Ukraïns’ki sorochky, ïkh typy, evoliutsiia i ornamentatsiia,’ Materialy do ukraïns’koï etnolohiï, 21–2 (1929)

Rosenberg, L.; Pavlenko, V. Ornamenty ukraïns’koho narodn’oho vyshyvannia (Kharkiv 1929)

Stechyshyn, S. Mystets’ki skarby ukraïns’kykh vyshyvok (Winnipeg 1950)

Ukrainskie narodnye dekorativnye rushniki (Moscow 1955)

Ukraïns’ki narodni vyshyvky (Kyiv 1957)

Kulyk, O. Ukraïns’ke narodne khudozhnie vyshyvannia (Kyiv 1958)

Al’bom narodnykh vyshyvok L’vivs’koï oblasti Ukraïns’koï RSR (Kyiv 1960)

Manucharova, N. (ed). Ukraïns’ke narodne mystetstvo: Tkanyny i vyshyvky (Kyiv 1960)

Narodni vyshyvky L’vivshchyny (Kyiv 1960)

Ruryk, N. Ukrainian Embroidery Designs and Stitches (Winnipeg 1958)

Markovych, P. Ukraïns’ki khrestovi vyshyvky Skhidnoï Slovachchyny (Prešov 1964)

Kutsenko, M. Ukrainian Embroideries (Melbourne 1977)

Wynnycka, J.; Zelena, M. (eds); Turko, J. Ukraïns’ka vyshyvka/Ukrainian Embroidery (Toronto 1982)

Kara-Vasyl’ieva, T. Poltavs’ka narodna vyshyvka Kyiv 1983)

Diakiw-O'Neill, T. Ukrainian Embroidery Techniques/Ukraïns’ki stiby (Mountaintop, Pennsylvania 1984)

Zakharchuk-Chuhai, R. Ukraïns’ka narodna vyshyvka: Zakhidni oblasti URSR (Kyiv 1988)

Kara-Vasyl’ieva, T. Liturhiine shyto Ukraïny XVII–XVIII st.: Ikonohrafiia, typolohiia, stylistyka (Kyiv 1996)

———. Ukraïns’ka narodna vyshyvka (Kyiv 1996)

Demian Horniatkevych, Lidiia Nenadkevych

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 1 (1984).]