Bakhmut

Bakhmut [Бахмут; Baxmut]. See Google Map. EU Map: V-19, DB Map: DBII-4. City (2020 pop 73,000), called Artemivsk from 1924 until 2016, under oblast administration in Donetsk oblast and administrative center of its eponymous raion. Located 89 km northeast of Donetsk on the Bakhmutka River (tributary of the Donets River), on the main north-south rail trunk line (double-track, electrified) from Kharkiv to the Donets Basin, and alongside the M-03 highway from Kharkiv through the Donets Basin, Bakhmut is also a railway and highway junction. From the Bakhmut junction north of the city a single track non-electrified line extends west to Chasiv Yar and on to Kramatorsk, and another one east to Soledar (the line from there to Popasna was abandoned since 1991). A site of the Bakhmut rock salt deposits, Bakhmut is the largest centre of salt industry in Ukraine. Deposits in Bakhmut and surrounding areas also yield gypsum, dolomite, chalk, and refractory clay.

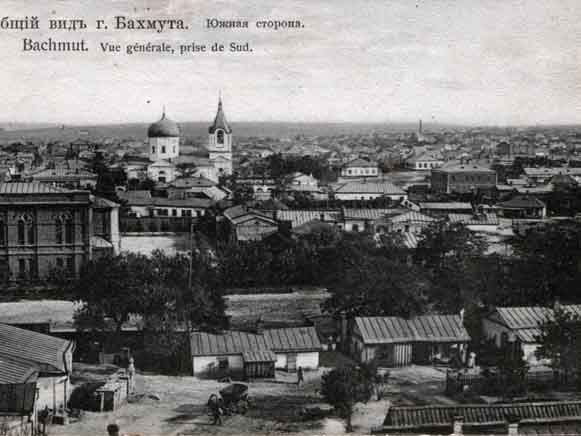

History. Mention of Bakhmut dates from 1571, when the Bakhmut guard (or Bakhmut Cossacks), on contract with the government in Moscow, patrolled its southern perimeter for Tatar incursions. After Crimean Tatars destroyed forts at Tor and Maiak (1697), the leader of the Cossack Izium regiment appealed to Tsar Peter I for permission to construct the fortress of Bakhmut, which they built in 1703. Salt procurement from its lakes, contested among the Don Cossacks, the Zaporozhian Cossacks, and the Izium Cossacks, was resolved with the defeat of the Don Cossack revolt led by Kondratii Bulavin (1707–8); it became a Russian state enterprise run by the Izium regiment. In 1732 the local parishioners and their priest, Ioan Lukianov, built the Church of the Holy Protectress (it has not survived). In 1748 the Bakhmut Horse Cossack regiment was established. Bakhmut served as a provincial administrative center within the Azov gubernia (1719–53, 1775–82). With the formation of Sloviano-Serbia in 1753, Bakhmut also served as its administrative center (1753–75) and hosted the formation of the Bakhmut Husar regiment (1764–65).

After Russia’s defeat of the Crimean Khanate (1774), the fear of Tatar raids was gone and access to the Black Sea was secured. In 1782 the Bakhmut saltworks were closed because of competition from the Black Sea salt. With territorial reorganization, in 1783 Bakhmut became a county town in Katerynoslav gubernia. Its fort, no longer needed, was closed. The economy also changed to 6 tallow melting operations, 5 brickworks, one each of candle, wax, and soap-making shops, with services of a hospital, 3 schools, and a biannual regional fair.

The abolition of serfdom in 1861 and the attraction of foreign capital accelerated industrialization. In the 1870s a number of plants were built: glass, nail, alabaster, and brick. The discovery of the huge Bakhmut rock salt deposits (1876) prompted the establishment of salt mines (1879). After the Kharkiv–Bakhmut–Popasna railway line was laid (1879), a salt processing plant was built in Bakhmut; the production of gypsum, soda, and tiles was added. By 1900 there were 76 small industrial enterprises (employing 1,078 workers) and 4 salt mines (874 workers). Metalworking did not begin to develop here until the beginning of the 20th century. The population of Bakhmut in 1897 was 19,300; the mother tongue of the majority was Ukrainian (61.8 percent), then Russian (18.9 percent), and Yiddish (16.7 percent).

On the eve of the First World War Bakhmut had 28,000 residents, 2 hospitals, 4 secondary schools and 2 vocational schools, private, parish, and folk schools, and a private library. Two local Russian-language newspapers began to appear: Bakhmutskaia kopeika and Bakhmutskaia zhizn'. The Bakhmut salt factory was closed in 1914 and never revived. Other salt mining and processing, however, opened at nearby Soledar.

The February Revolution of 1917 in Russia brought about the emergence of political parties and free elections. A regional conference representing 132 deputies from 48 local councils proposed an idea of establishing the Donets Basin as a separate region. An election held to elect the city council was won by the Social-Democratic Bloc. The Ukrainian revival of the city began after the Central Rada in Kyiv issued the Third Universal of the Central Rada (20 November 1917), which proclaimed the Ukrainian National Republic (designating its territory and its federal relationship with Russia). In response, the Bakhmut county council raised, for the first time, the blue-and-yellow Ukrainian flag; in Bakhmut and nearby villages, Ukrainian political parties, branches of Prosvita societies and of Free Cossacks (volunteer militia) were organized. Newspapers began to be published in Ukrainian: Bakhmuts'ke zhyttia, Donets'ke slovo, and Narodna hazeta. By December 1917, however, the Bolsheviks from Luhansk challenged the authority of the Ukrainian government, aptured Bakhmut, and in February 1918 declared their Donets–Kryvyi Rih Soviet Republic, chaired by Fedor Sergeev (pseudonym Artem). On 26 April 1918, with the support of the Austro-German military, the city was liberated by the Sloviansk contingent of the Zaporozhian Corps of the Army of the Ukrainian National Republic Army, under the command of Col Volodymyr Sikevych, and then secured by the Third Haidamaka Regiment (see Haidamaka Battalion of Slobidska Ukraine) under the command of Otaman Omelian Volokh. The Bakhmut residents were not happy with the Hetman government of Pavlo Skoropadsky, who took over in a coup supported by the Germans, and staged a rebellion in support of its challenger, the Symon Petliura-led Directory of the Ukrainian National Republic. With the withdrawal of the German forces, the city was captured in November 1918 by the Volunteer Army’s ‘White’ Cossacks led by General Petr Krasnov. On 25 December 1919 the Red Army drove out the ‘White’ forces and took over Bakhmut.

In 1920–5 Bakhmut served as the administrative center of Donetsk gubernia. Its main newspaper became Vpered. In 1924 Bakhmut was re-named Artemivsk (after the the Bolshevik leader Artem who came to live in the city), and then designated as the center of the Artemivsk okruha (1925–30). With industrial expansion, the population of the city grew and diversified. In 1926, Artemivsk had 38,000 residents, of whom 54.1 percent were identified as Ukrainians, 23.5 percent as Russians, and 17.5 percent as Jews; other minorities included Poles (0.9 percent) and Germans (0.6 percent).

In 1930–2 the city was purged of Ukrainian intelligentsia: teachers and activists from the time of Ukraine’s struggle for independence (1917–20) were arrested and executed. By mid-1930s 70 percent of the library holdings of the city were destroyed. During the Famine-Genocide of 1932–3 the city lost 3,255 citizens. During the Second World War Artemivsk was occupied by the German forces from 1 November 1941 until its recapture by the Soviet Army on 5 September 1943. After the war the city recovered and experienced moderate industrial and population growth: 57,000 (1956), 63,000 (1959), 82,000 (1970), 87,000 (1979), 91,000 (1987). Population peaked at 92,000 in 1993 and began to decline in 1995.

After the 1991 Ukraine’s Declaration of Independence, self-identification as Ukrainian became less problematic, but the legacy of linguistic Russification was indicative. In 2001 the city of Artemivsk had 83,000 inhabitants, while Artemivsk city council (which at the time included the adjoining cities of Soledar, Chasiv Yar, and the town of Krasna Hora) had 114,000 inhabitants, of whom 69.4 percent identified themselves as Ukrainians, and 27.5 percent as Russians; other minorities included Belarusians (0.6 percent), Armenians (0.4 percent), Gypsies (0.2 percent), and Jews (0.2 percent). Of the Ukrainians, 50.8 percent indicated Russian as their mother tongue; of the Russians, by contrast, 3.2 percent indicated Ukrainian as their mother tongue. Public worship revived and churches were built. In 2020 Bakhmut city council had on registry 8 Ukrainian Orthodox church parishes, 2 Baptist, and one each of Roman Catholic, Muslim, Jewish and 4 other sects.

On 12 April 2014, Artemivsk was taken by the pro-Russian forces and included in the so-called ‘Donetsk People’s Republic.’ By 6 July 2014 the Ukrainian forces liberated the city. In keeping with the law on de-Communization, the city removed its monument to Artem (10 July 2015), voted to rename its city and over 80 streets (23 September 2015); by legislation in Kyiv, the city officially regained its historic name, Bakhmut, on 4 February 2016.

Economy: Bakhmut is an important industrial center. Historically, the salt industry stands out. Mining of the Bakhmut rock salt deposits (5 billion t reserve estimated in 1986) reached an output of 6.8 million t in 1985 (or 23 percent of the total in the USSR). Its output has declined to 3.6 million t (2013), about one-third of Ukraine’s total production. Although Bakhmut hosts the head office of the ‘ArtemSil’ corporation, its mines are located in Soledar, 12 km north-northeast of Bakhmut. As of 2016, the mines and processing plant were undergoing modernization. Other industries based on local minerals include the production of alabaster and gypsum (mined and processed in Soledar by the German Knauf Gips Donbass Corporation, est 2003, and mined and made into building materials by Siniat Corporation in Bakhmut, privatized in 1995), ceramic tiles and drains, firebricks (made from refractory clays, mined and processed at Chasiv Yar), and glass. The production and metal-working of non-ferrous metals (since 1954 the main products have been copper and brass bars and sheets), machine-building, and pharmaceutical industry gained importance in the Soviet period. Infrastructure building is represented by electric network and road construction enterprises. Consumers are served by the food industry (meat-processing, dairy, baking, distilling, and especially wine-making; a champagne distillery was built in 1950 and in 1970 produced 8.2 million bottles), as well as wood-working, furniture-making, and light industry (sowing, shoe-making).

Culture and Education. In the Soviet period the scientific and educational institutions focused mainly on support for industrial development. The All-Union Research Institute for the Salt Industry, the All-Union Project-Building Bureau of Salt Industry, the Industrial Association Donbasheolohiia, the Donetsk Geophysical Expedition (now a branch of Ukrheofizyka) and a research station for grape-growing and orchards. A regional studies museum and geological museum were established in Bakhmut. Educational facilities included 5 special vocational schools and 5 vocational-technical schools, including the re-named Bakhmut College of Transport Infrastructure and the Bakhmut Medical College. After the 1991 Ukraine’s Declaration of Independence two schools in humanities also were re-named colleges: the Bakhmut Pedagogical College (formerly the Artemivsk Teacher’s Institute, est 1930s, re-organized in 1954), and the Ivan Karabyts Bakhmut College of Arts (est as private school by the Vienna Conservatory alumna, Adel Mereines, in 1903, gained status of a music school in 1926, named after its own alumnus and composer, Ivan Karabyts in 2004, and assumed its present name in 2016). Bakhmut did not gain a university.

The city has 12 libraries, including one for the blind. Athletic facilities are adequately developed, represented by the Avanhard stadium, and the large renewed Metallurh sports complex.

Mass media is represented by Russian-language newspapers, like Sobytiia, and Vpered. There is local television and radio transmission: 9 analog TV channels, cable TV, 2 FM radio stations, and an internet publication in Ukrainian: bahmut.in.ua.

City plan. On a map the city of Bakhmut forms a star-like cross, the extensions along the main intersecting thoroughfares reaching 8.7 km from east to west and 9.8 km from north to south. The city’s area is 41.5 sq. km, of which about 70 percent is built up, the rest in parks, fields, and gardens. The city boasts 1,072 hectares (26 percent of its area) in plantings.

Industrial plants and mines are outside the city center, serviced by railway spurs from the Bakhmut junction. One spur to the northern part of the city center serves the non-ferrous metals plant and the road construction plant; another spur branching off to the east across the Bakhmutka River serves the ‘Siniat’ gypsum mine, the ‘Siniat’ building materials plant, the furniture factory and the Bakhmut Structural Ceramics factory.

The city center hosts the majority of Bakhmut’s civic, cultural, educational, and religious institutions as well as sports complexes. The city center is framed by the Bakhmutka River in the east, the north-south rail trunk line with its main railway station in the west, the spur line terminus with factories in the north, and Bakhmut Street in the south. In the middle of the city is the Freedom Square, bound by Freedom Street (formerly Lenin Street) in the north and Peace Street (formerly Artem Street) in the west and Independence Street (formerly Soviet Street) in the east, with the the City Culture Center overlooking it from the south and the city hall from across Peace Street in the west. A large bronze statue of Artem dominated the square until it was removed in 2015. A promenade through two parks also graces the city center. Located northwest of Freedom Square, it leads from the Lower Park (with a monument to Soviet soldiers) westward, towards and through the Upper Park (with an obelisk, the All Saints Church to the north, and a children’s playground to the south of it), ending at the park-like Bakhmut Station Square. Among other civic institutions in the city center are the raion administration building, hospitals and clinics, court houses, and the city jail; educational establishments (colleges and schools), libraries, museums, the Metalurh sports complex and Avanhard stadium, and the central market. No old churches survived, but after the 1991 Ukraine’s Declaration of Independence new ones were built, including the Church of the Mother of God, the Guarantor of Sinners Chapel at the city jail, and the Mother of God Holy Rosary Roman Catholic Church.

Public transport in the city is provided by trolleybuses (6 routes) and buses, supplemented by private minibuses and taxis. There are four railway stations in the city: the Bakhmut main station, Bakhmut 1 (north of the city center), Maloilshivska (on the main line north of the main station), and Stupky (at the railway junction, in the north end of the city).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

‘Artemivs'k’ in Heohrafichna entsyklopediia Ukraïny (Kyiv 1989)

Pirko, V. ‘Naidavnishi mista Donechchyny (mify i realnist')’ in Skhid, September 2004

Tatarinov, S. Bakhmut kazatskii: neizvestnye stranitsy istorii XVII–XVIII stoletii (Artemivsk 2004)

‘Artemovsk: Plan goroda’ 1:14,000 in Mista Ukraïny (Kyiv 2009)

‘Bakhmut: Plan goroda’ 1:14,000 in Mista Ukrainy (Kyiv 2016)

Ihor Stebelsky

[This article was updated in 2020.]

.jpg)

.jpg)