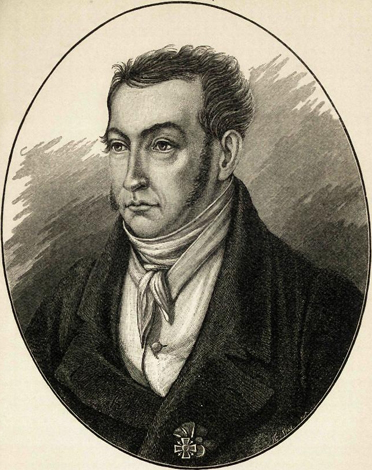

Narezhny, Vasilii

Narezhny, Vasilii or Narizhny, Vasyl [Наріжний, Василь; Narižnyj, Vasyl'; Russian: Нарежный, Василий; Narežnyj, Vasilij], b 13 January 1780 in Ustyvytsia, Myrhorod county, Little Russia gubernia, d 3 July 1825 in Saint Petersburg. A Russian writer of Ukrainian origin, representative of the Ukrainian school in Russian literature of the early 19th century. Vasyl Narizhny’s father, Trokhym, belonged to petty gentry in the Poltava region and served as sergeant major in the Chernihiv Carabineer Regiment. Retired in 1786, he was granted hereditary nobility for his outstanding service; his estate was small and he had no serfs, so he cultivated the land himself. Vasyl received his primary education at home under the supervision of his uncle Andriievsky-Narizhny. Based on the analysis of Narezhny’s later novel Bursak (The Seminarist, 1824), his biographers conclude that the writer must have also studied in a bursa (theological seminary), probably either in Chernihiv (the former Chernihiv College; as per N. Belozerskaia), or in Pereiaslav (the former Pereiaslav College; as per Volodymyr Doroshenko). From 1792 he studied at the gymnasium for the children of nobility at Moscow University, and at the philosophy department of the same university afterwards (1799–1801).

While still a gymnasium student, Narezhny began to write poetry in Russian and produce translations of literary works. His first poems were published in 1798. The pre-romantic tendencies inspired Narezhny to turn to the themes from the history of Kyivan Rus’, which became the subject of his historical-heroic poem ‘Brega Alty’ (Banks of the Alta River, 1798) about the internecine wars among the sons of Prince Volodymyr the Great. Also in 1798, he wrote a poem based on Slovo o polku Ihorevi (The Tale of Ihor’s Campaign), which indicates that he was familiar with the text of Slovo before its first publication in 1800. As a Russian-language poet, Narezhny was the first to use the five-line iambic pentameter, which would become one of the most popular verses in Russian poetry and which Aleksandr Pushkin would later utilize in his tragedy Boris Godunov.

Narezhny also tried his hand at drama: in the early 1800s, he wrote two tragedies: Krovavaia noch', ili konechnoie padenie doma Kadmova (A Bloody Night, or the Final Fall of the House of Cadmus) which contained transparent allusions to his contemporaneous times, in particular to the despotism of Tsar Paul I; and Dmitrii Samozvanets (Dmitrii the Pretender, 1804) which focused on the theme of relations between a tyrant and the people. These plays demonstrate Narezhny’s thorough familiarity with the ancient Greek tragedies of Aeschylus and Sophocles; being proficient in ancient Greek, Narezhny read their dramas in the original. A theme from the history of Cossack period served as a basis for the plot of Narezhny’s anonymously published play Den' zlodeistva i mshcheniia (The Day of Villainy and Vengeance, 1806). Dating the events portrayed in the play to the 1780s, the author created an image of a noble outlaw Chornomor (son of Count Lesnytsky) who, following the liquidation of the Zaporozhian Sich, returned home accompanied by his fellow Cossacks in order to take revenge on a local landowner Zelsky, who had brought dishonor to his family.

Narezhny temporarily abandoned his literary aspiratons in 1801, when he relocated to Tbilisi to serve at the local government formed after Russia annexation of Georgia. He later depicted his impressions of his time in the Caucasus Mountains in his novel Chernyi god, ili gorskiie kniaz'ia (The Black Year, or the Highland Princes) that was published posthumously in 1829. In his novel, Narezhny disapprovingly described the lawlessness of government officials of various ranks, the civilian ruler of Georgia, Kovalensky, and the military lieutenant general, Knoring, while underscoring the imperial Russian disregard for national customs and traditions of the Caucasian peoples.

In May 1803 Narezhny moved to Saint Petersburg, where he served as an official in various ministries and departments of the imperial government. He did not actively participate in the city’s literary life, although his novel Rossiiskii Zhil' Blaz (The Russian Gil Blas, 1814) contains echoes of the literary polemics of that time, in particular, the discussions between the admirers of Nikolai Karamzin and Aleksandr Shishkov. Also, Narezhny’s talent was recognized by members of the Free Society of Lovers of Russian Literature who, taking into account ‘his impoverished circumstances,’ granted him an allowance of 300 rubles, while at the same time refusing to publish his novel Chernyi god.

In 1809, returning to historical themes, Narezhny published his first historical novel Slovenskie vechera (Slavic Evenings), the sequel to which appeared posthumously in 1826. In the late 1810s, short stories ‘Liuboslav,’ ‘Aleksandr,’ and ‘Igor’ were published as a response to the society’s demand for literature on heroic and patriotic themes following the Napoleonic War of 1812. According to N. Belozerskaia, these works represent a mixture of themes from Rus’ chronicles and epics, motifs from Western European novels, and the author’s original creative inspiration. The poetics and style of these stories are related to pre-Romanticism with its attention to folk oral literature and historical reflection and an emphasis on the heroization of the past. The genres of Russian romantic short story and novella, which became popular in the 1820s, was influenced by Narezhny’s works. However, in spite of the popularity of his historical stories, Narezhny felt dissatisfied with the limited range of their themes and returned to the genre of a novel.

Under the influence of French novelistic literature, including Alain René Lesage’s Adventures of Gil Blas of Santillane, Narezhny turned to the genre of picaresque novel, which had been popular since the baroque era. The first three parts of his novel Rossiiskii Zhil' Blaz, ili pokhozhdeniia kniazia Gavrily Simonovicha Chistiakova (The Russian Gil Blas, or the Adventures of Prince Gavrila Simonovich Chistiakov) were published in 1814; the following three parts were banned by the censors due to the author’s sharp satirical portrayal of landowners and serfdom, and the novel was published in its entirety only in 1938. Some scholars (including Halina Mazurek-Wita) believe that Narezhny’s satirical works deserve to be considered among the best works of this type the European literature of that period. Built around a series of adventures experienced by a reckless nobleman, the structure of Rossiiskii Zhil' Blaz presents an extensive, multifaceted, and multidimensional portrayal of morals and social customs of Narezhny’s time. The novel’s plot is partly based on themes from the Ukrainian literary tradition, including moral tales, folk songs, intermedes, nativity plays, and homilies; in general, a burlesque-travesty style of the Ukrainian baroque and traditional folk culture had a powerful impact on the poetics of Narezhny’s works. This influence of the Ukrainian baroque tradition—intimately familiar to Narezhny, but unknown to his Russian readers—has resulted in certain misinterpretations of Narezhny’s novel by Russian literary critics, including Petr Viazemsky who explained Narezhny’s specific (and unusual for Russian literature) approach to literary style and subject matter by the fact that the author was ‘not exactly a Russian writer, but a Little Russian one.’ Mikhail Bakhtin saw the essence of Narezhny’s literary sensibility to be the result of his close affinity to the Ukrainian baroque ‘culture of popular laughter’ that included folk anecdotes as well as satirical works by itinerant tutors and wandering seminarists (bursaks).

Narezhny’s novels and short stories of the 1820s are even more closely connected to the Ukrainian baroque literature. In 1824 his Novyie povesti (New Novellas) were published, including Zaporozhets (The Zaporozhian Cossack) and Zamorskii prints (A Prince from Overseas). The first novella contains, among other things, a portrayal of life of the Cossacks in Zaporozhian Sich, which foreshadows, in many ways, the treatment of this topic by Nikolai Gogol (Mykola Hohol) in his Taras Bulba. The plot of Zamorskii prints (originally presented in the part of Rossiiskii Zhil' Blaz that was banned by censorship) features a protagonist who is a proud descendant of Cossack hetmans and the story exhibits Narezhny’s intimate knowledge of the Ukrainian folk demonology (in his treatment of the werewolf motif).

Narezhny’s novel Bursak (The Seminarist, 1824; Ukrainian translation by Volodymyr Doroshenko published in 1928) has been praised by critics as a new step in the development of historical novel in the Russian literature. For example, in her monograph dedicated to Narezhny’s work, N. Belozerskaia praised this novel as the first ‘real, rather than fantastic description of Little Russia’s everyday life’ during the times of the Cossack Hetman state. In particular, the author skillfully reproduced the daily existence of Ukrainian seminarists. The story centers on a seminarist Neon Khlopotynsky, who, like a hero of an adventurous novel, undergoes many challenging quests while traveling through 17th-century Ukraine. At the same time, detailed descriptions of life at the theological seminary or at hetman’s court provide a realistic historical background for the adventure story. The novel was popular with readers. According to the testimony of his brother, Andrii, Fyodor Dostoevsky loved and was influenced by Narezhny’s works and, in particular, he reread Bursak many times.

Narezhny left an unfinished novel Garkusha, malorossiiskii razboinik (Harkusha, the Little Russian Outlaw), based on the life of a real historical figure. The Cossack Harkusha’s real name was Semen Mykolaienko (1739–after 1784). He took part in the Koliivshchyna rebellion and in the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–74. In the early 1770s, he was a leader of a Cossack uprising, was arrested several times, and escaped, the last time in 1784 from Romny, where he was sentenced to life imprisonment; he has not been heard from since. Harkusha was a type of Ukrainian Robin Hood who used to give his loot to churches. In his unfinished novel Narezhny focused his attention on the reasons why Harkusha became a robber, and thus, rather than trying to recreate historically accurate story of his protagonist, the author addressed broader social issues, such as the question of an individual’s relationship with his or her social milieu. The main tenor of his treatment of Harkusha’s story is suffused with the idea that the world is ruled by social injustice.

In the 1820s Narezhny reportedly showed an increased interest in Ukraine and Ukrainian national movement. In a letter to Ivan Franko Mykhailo Drahomanov stated that Narezhny ‘was the center of a rather large Ukrainian circle preparing the field in Saint Petersburg’ for the appearance of Mykola Hohol, Istoriia Rusov, and Taras Shevchenko.

In 1825, two weeks after Narezhny’s death, his novel Dva Ivana (Two Ivans) was published. It was a narrative about a lawsuit between two Ivans (Zubar and Khmara) and Kharyton Zanoza, a situation that began from a trivial misunderstanding and escalated into a veritable battle. The story is remarkable for the realistic depictions of everyday life of Ukrainian gentry and for its folk humor, although the conflict itself is resolved in the literary traditions of the Enlightenment. Artamon, a personification of an enlightened virtuous individual who lives separately from other people, plays the role of a peacemaker, puts a stop to the confrontation, and metes out punishment to the guilty.

Russian literary critics, such as Vissarion Belinsky and Ivan Goncharov, recognized Narezhny as ‘the foremost Russian novelist of his time’ and the forerunner of Nikolai Gogol. Narezhny was indeed a precursor of Gogol in his depictions in the Russian literature of historical and contempraneous life of Ukrainians. He accomplished this task by utilizing, among others, the various forms and genres of the Ukrainian baroque literature. Similar stylistic elements were later further masterfully developed by Gogol in his prose works.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Belozerskaia, N. Vasilii Trofimovich Narezhnyi: istoriko-literaturnyi ocherk. Izd. 2-ie ispravlennoie i dopolnennoie (Saint Petersburg 1896)

Mazurek-Wita, H. Powieści Wasyla Narożnego na tle prozy satyryczno-obyczajowej XVIII i pochątku XIX wieku (Wrocław 1978)

Mykhed, P. ‘Izobrazheniie lichnosti G. S. Skovorody v romane V. T. Narezhnogo Rossiiskii Zhil' Blaz,’ Voprosy russkoi literatury no. 1 (Chernivtsi 1978)

———. ‘Na putiakh k istoricheskomu romanu’ in Zhanrovyie formy v literature i literaturnoi kritike (Kyiv 1979)

———. ‘Narizhnyi i baroko (do problem styliu pys'mennyka,’ Radians'ke literaturoznavstvo no. 11 (Kyiv 1979)

Pavlo Mykhed

[This article was updated in 2025.]