Right-Bank Ukraine

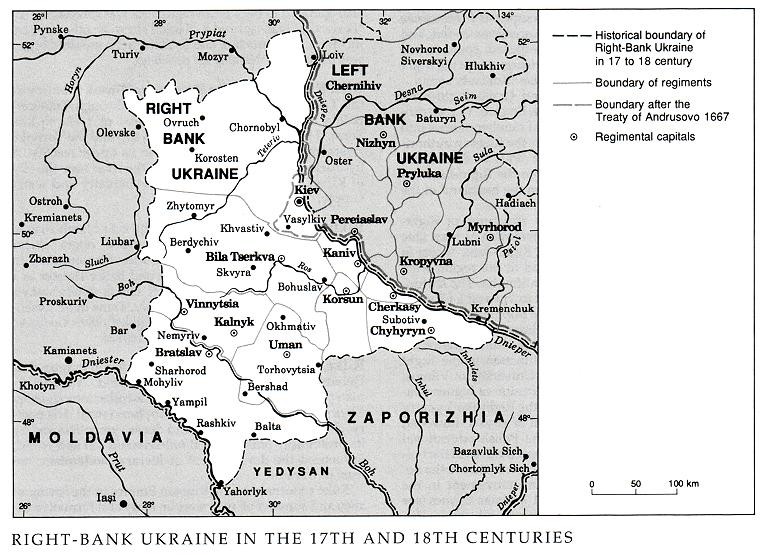

Right-Bank Ukraine (Правобережна Україна, Правобережжя; Pravoberezhna Ukraina, Pravoberezhzhia). (Map: Right-Bank Ukraine in the 17th and 18th centuries.) A historical, geographic, and administrative region consisting of the Ukrainian lands west of the Dnipro River, south of the Prypiat River marshes, north of the steppes, and east of the upper Boh River and the Sluch River. The Right-Bank Cossack administration included five core regiments (Chyhyryn regiment, Cherkasy regiment, Korsun regiment, Kaniv regiment, and Bila Tserkva regiment) and four frontier regiments (Uman regiment, Bratslav regiment, Vinnytsia regiment, and Pavoloch regiment). Under Polish control the region formed the Kyiv voivodeship (without the city and its environs) and Bratslav voivodeship as well as portions of Volhynia voivodeship and Podilia voivodeship. Under imperial Russian rule in the early 19th century, the Right Bank was renamed the Southwestern land. Right-Bank Ukraine today encompasses Vinnytsia oblast, Zhytomyr oblast, northern Kirovohrad oblast, and (west of the Dnipro River) Kyiv oblast and Cherkasy oblast.

Right-Bank Ukraine developed under the Cossacks as an important political, cultural, and economic region. Following the death of Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky in 1657, it was devastated and depopulated during the Ruin as a result of prolonged fighting among the Cossacks, Poland, Muscovy, and Turkey. The destruction was aggravated by the instability of the Cossack structure itself, which was split in 1660 when Left-Bank Ukraine's regiments rejected the leadership of Yurii Khmelnytsky and elected their own hetman (Yakym Somko). Their action initiated the political division of Ukraine into Left and Right Banks, which acquired significance in international affairs with the Polish-Muscovite Treaty of Andrusovo, by which Muscovy and Poland ratified their respective spheres of influence along the Dnipro River: Muscovy received Left-Bank Ukraine plus Kyiv with its environs, and Poland received Right-Bank Ukraine.

The treaty ended the pro-Polish orientation of successive Right-Bank Cossack leaders and initiated nearly a half-century of chaos in the Right Bank. Hetman Petro Doroshenko rejected both Muscovite and Polish interference and unified both banks (1668) under his leadership. His achievement, however, was short-lived, and he was forced to return to the Right Bank, at which time Muscovy restored its influence in Left-Bank Ukraine. Doroshenko then turned to Turkey for assistance (the result being the Buchach Peace Treaty of 1672) and embroiled the region in a succession of maneuvers for control. In 1676 the Left-Bank hetman Ivan Samoilovych defeated Doroshenko and briefly united both banks under his hetmanship. Pressed by Turkish forces, Samoilovych attempted in 1678 to remove the Right-Bank population to Left-Bank Ukraine and Slobidska Ukraine. The Treaty of Bakhchysarai (1681) delineated the Dnipro River as the boundary between the Ottoman and Muscovite empires, with the southern Right Bank a vacant neutral zone. The Eternal Peace of 1686 between Muscovy and Poland confirmed the previous Treaty of Andrusovo, whereby Poland retained the Right Bank. Ukraine was now completely partitioned among its three neighbors.

In 1685, as protection against Tatar raids, the Polish king Jan III Sobieski established Cossack regiments in Bratslav, Bohuslav, Korsun, and Fastiv, but under a royally appointed hetman and officers. Some Cossacks also served as mercenaries in the magnates' armies.

By the terms of the Treaty of Karlowitz (1699) Poland regained control of the Right Bank from Turkey. That year the Cossack administration was formally abolished in the Right Bank, but a Cossack uprising in 1700–3, led by Col Semen Palii, briefly overthrew Polish rule in the Right Bank; Left-Bank hetman Ivan Mazepa took advantage of the confusion to unite both banks under his rule. By the Prut Treaty of 1711, however, Right-Bank Ukraine was returned to Poland. The Cossacks were then completely suppressed.

Because continual warfare had destroyed the towns and villages and depopulated the Right Bank, the Polish and Polonized Ukrainian magnates upon their return offered incentives to the peasantry of northwestern Ukraine, especially Volhynia, to resettle the Right Bank. Peasants were promised 15 to 20 years of exemptions from corvée and other obligations. When the concessions ended, and the obligations of serfdom were imposed, spontaneous anti-Polish peasant haidamaka uprisings swept the Right Bank, in 1734, 1750, and 1768 (see also Koliivshchyna rebellion).

By the Third Partition of Poland (1795) Right-Bank Ukraine was annexed by the Russian Empire. That territorial acquisition brought a substantial number of Jews into the imperial realm for the first time; the Russian authorities responded by establishing the Pale of Settlement, which restricted Jewish settlement to the Right-Bank regions and other areas removed from the heartland of the empire.

Several distinctive features and structures of Right-Bank Ukraine persisted until the Revolution of 1917. One was the extensive influence of the Right-Bank Poles. As well, vast tracts of land in the region were worked as large estates known as latifundia. The latifundia system hampered the growth of towns and a Ukrainian urban middle class. Towns were populated predominantly by Jewish merchants and artisans.

In the early 19th century the tsarist administration allowed a Polish school system to function in the Right Bank, under the supervision of the University of Vilnius. The school system included an institution of higher education, Kremenets Lyceum. After the Right-Bank gentry took part in the Polish Insurrection of 1830–1, however, the tsarist authorities abolished the Polish educational system in the Right Bank. Some representatives of the Polish gentry in the early 19th century contributed to the development of the nascent Ukrainian movement in the Right Bank by writing literature on Ukrainian themes (see Ukrainian school in Polish literature) and conducting ethnographic research on the Ukrainian peasantry.

On the eve of the Polish Insurrection of 1863–4, some students from the Polonized Ukrainian gentry, including Volodymyr Antonovych, broke with Polish society and returned to their Ukrainian roots. Known as the khlopomany (lovers of the peasantry), they contributed much to the development of the Ukrainian national awakening in the Right Bank.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Krykun, Mykola. Administratyvno-terytorial’nyi ustrii Pravoberezhnoï Ukraïny v XV–XVIII st.: kordony voievodstv u svitli dzherel (Kyiv 1993)

Krykun, Mykola. Mizh viinoiu i radoiu: kozatstvo Pravoberezhnoï Ukraïny v druhii polovyni XVII – na pochatku XVIII st.: Statti i materiialy (Kyiv 2006)

Andrew Beniuk

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 4 (1993).]