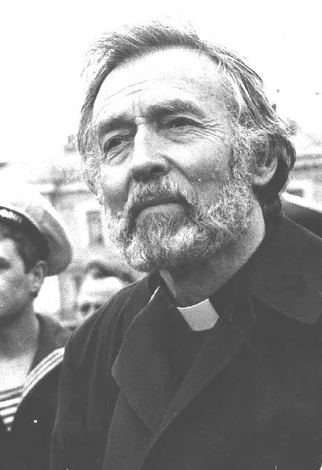

Romaniuk, Vasyl

Romaniuk, Vasyl or Patriarch Volodymyr (Romaniuk) [Романюк, Василь or Патріярх Володимир; Romanjuk, Vasyl' or Patriarch Volodymyr], b 9 December 1925 in Khimchyn, Kosiv county, Stanyslaviv voivodeship, Galicia, d 14 July 1995 in Kyiv. Human rights activist, dissident, and political prisoner, Orthodox bishop (from 1990), patriarch (from 1993). He completed his elementary education in Khimchyn before attending an agricultural school in Kosiv. From August 1943 he was involved in the underground activities of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), serving as a courier. On 12 July 1944 he was arrested by the NKVD in Stanislav oblast (now Ivano-Frankivsk oblast). On 26 September 1944 the military tribunal of the NKVD troops of the Stanislav oblast sentenced Romaniuk to 20 years in the GULAG labor camps, with the confiscation of all property, and to an additional five-year term of deprivation of civil rights. The official charges against him included membership in the OUN, performing duties of a courier, and reading and distributing nationalist literature. On 28 October 1944, following a review of his appeal, the military tribunal reduced Romaniuk’s sentence to 10 years. As a result of his arrest, a special meeting of the NKVD of the USSR on 21 April 1945 ordered the deportation of his father, Omelian, his mother, Hanna, and his two brothers to a special settlement in Siberia for a period of five years.

Romaniuk was imprisoned in Kustolivka Labor Colony no. 17, under the jurisdiction of the NKVD department in Poltava oblast. On 9 April 1946 he was again arrested by the colony administration on fabricated charges of belonging to a fictitious clandestine ‘Ukrainian Sich Riflemen’ group, engaging in anti-Soviet propaganda, and planning an escape. On 18 June 1946 he was sentenced by the Special Camp Court of Labor Camps and Colonies of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Ukrainian SSR to ten years of imprisonment, to be served in remote regions of the USSR; his sentence also included an additional five-year term of deprivation of civil rights and confiscation of all of his personal property.

He served his sentence in the GULAG camps in Magadan oblast (Kolyma) in the Far East and was released on 9 August 1953. From 28 August 1953 he lived in a special settlement in the city of Magadan. On 24 August 1954 he married Mariia Antoniuk who had been sentenced in 1944 to ten years’ imprisonment for her alleged ties to the OUN. Between 1955 and 1957 he worked at a bakery and later as a cinema projectionist, while completing his secondary education. In 1956–58 he repeatedly petitioned for a review of his 26 September 1944 verdict; eventually, on 3 February 1959, following numerous interrogations of witnesses and Romaniuk himself, the military collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR annulled his sentence. In the meantime, on 19 March 1956 he was released from the special settlement, and in 1958 he returned to Ukraine.

In 1958 Romaniuk entered the Higher Theological Courses under the Stanislaviv eparchial administration of the Russian Orthodox church. On 16 November 1959 he was ordained a deacon and served in Kosiv and surrounding villages. Due to opposition from KGB and religious-affairs officials, who acted in line with Nikita Khrushchev’s anti-religious policy of 1958–64, he was initially denied ordination to the priesthood. In 1961 he briefly served as a deacon in Omsk, Western Siberia, RSFSR, and from 1961 to 1963 he lived in the settlement of Kurhan, Balakliia raion, Kharkiv oblast, where his mother and brothers resided. During this period he worked as a cinema projectionist. In the autumn of 1963, he returned to Ivano-Frankivsk oblast.

On 26 April 1964 in Ivano-Frankivsk he was ordained a priest by Bishop Yosyf Savrash of Ivano-Frankivsk and Kolomyia. In the same year he enrolled in the correspondence courses program at Moscow Theological Seminary. From 1964 to 1968 he served in the villages of Novoselytsia, Popelnyky, and Dzhuriv, Sniatyn raion, Ivano-Frankivsk oblast. From the autumn of 1968 until 1971 he served in Kosmach, Kosiv raion. He maintained contacts with members of the dissident movement, as well as Ukrainian poets and artists, and collected works of Hutsul folk art. On 6 February 1971 he performed the baptism of Viacheslav Chornovil.

Under pressure from the Soviet authorities, Romaniuk was forbidden to conduct religious services from 25 February to 25 March 1970, after Christmas celebrations in Kosmach turned into large-scale and festive events. On 26 November 1970 he submitted a petition to the Supreme Court of the Ukrainian SSR in defense of historian Valentyn Moroz, who had published articles in the Ukrainian émigré journals Vyzvol’nyi shliakh and Suchasnist’. The text of his petition was later broadcast by Radio Liberty. Because of his active religious and civic activities, and under increasing scrutiny of the authorities, in February 1971 he was transferred from Kosmach to serve in the village of Prutivka, Sniatyn raion, Ivano-Frankivsk oblast.

From 29 September to 1 October 1971 Romaniuk was held under arrest on charges of producing and distributing anti-Soviet materials. He was arrested again on 20 January 1972 on charges of conducting ‘anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.’ On 12 June 1972 the Ivano-Frankivsk oblast court found Romaniuk to be ‘a particularly dangerous repeat offender’ and sentenced him to seven years of imprisonment followed by three years of internal exile, stipulating that the first two years were to be served in prison and the remainder in a high-security labor camp. From 1972 to 1973 he was held in a prison for political prisoners in Vladimir, RSFSR, and in early 1974 he was transferred to a high-security labor camp in the settlement of Sosnovka, Zubovo-Polianskyi raion, Mordovian ASSR.

In the summer of 1975 Romaniuk wrote an appeal to the World Council of Churches, calling on the council to defend believers and cultural figures persecuted in the USSR. In similar letters addressed to Pope Paul VI, he urged to pay attention to the plight of repressed women and proposed the establishment of an international commission to investigate human rights violations in the Soviet Union. On 1 August 1975 he declared a hunger strike in protest against the brutal suppression of basic human rights in the USSR and he demanded the right to possess and read a copy of the Bible. On 1 July 1976 he sent a letter to the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR renouncing his Soviet citizenship, and on 4 June of the same year he appealed to the United States Congress and government to grant him American citizenship.

In 1977–79 Romaniuk continued to write letters of protest to various international human rights and religious organizations, urging them to take active measures against the Soviet regime’s violations of human rights. In 1977 in a letter to the editorial office of the Vatican newspaper L’Osservatore Romano, he focused specifically on the Soviet persecution of the Ukrainian Catholic church (Romaniuk himself had been born into a Greek-Catholic family) and called for efforts toward its legalization in the USSR. In a letter that reached the West in the spring of 1978, addressed to Metropolitan Mstyslav Skrypnyk, Romaniuk stated that he regarded himself as a member of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox church (UAOC) and that he only formally belonged to the Russian Orthodox church; he also requested assistance in securing the emigration for his wife and son, and, after his release, for himself as well. In response to these appeals, representatives of the Ukrainian Orthodox churches and the Ukrainian Catholic church in the United States of America called on the international community to support the imprisoned clergyman. Similar initiatives were undertaken by international human rights and religious organizations.

In 1978 together with 18 other Ukrainian political prisoners in the Mordovian labor camps, Romaniuk signed the document entitled ‘The Position of Ukrainian Political Prisoners,’ which articulated the moral and ideological principles guiding imprisoned Ukrainian dissidents who were described in this letter as the ‘conscience of the nation’ in Ukraine’s struggle for independence. At the beginning of 1978 Romaniuk also wrote a letter to President Jimmy Carter, in which he again urged the United States of America to defend human rights in the USSR. Together with other prisoners he signed similar appeals addressed to the Parliament of Canada, the Committee for the Defense of Human Rights in the USSR, and the Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords.

On 18 January 1979 Romaniuk was released from imprisonment and sent into exile to the settlement of Sangar, Yakutia ASSR, where he worked as a night watchman and fireman. In February 1979 he became a member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group. In September 1981 he returned to Ukraine and settled in Kosiv, where he worked as a laborer for the Kosiv Agricultural Equipment Enterprise and, beginning in 1982, as a janitor at a local hospital. In 1982 he applied for permission to emigrate permanently to Canada, but the Soviet authorities denied his request.

In early 1983 Romaniuk suffered his first heart attack, and his health deteriorated significantly. He also remained under constant surveillance and pressure from the KGB. On 4 February 1983 he submitted a statement to the Commissioner for Religious Affairs of the Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast Executive Committee, expressing regret for actions that had been classified by the courts as anti-Soviet activity and assuring the Soviet authorities and the leadership of the Russian Orthodox church that he would refrain from any actions harmful to the Soviet state. This statement, published on 4 March 1983 in the newspaper Prykarpats’ka pravda, was viewed critically by some dissidents. After its publication, Romaniuk was allowed to resume church ministry and was assigned to the village of Babyn, Kosiv raion, Ivano-Frankivsk oblast. His wife passed away there in March 1985. In the spring of 1986 Romaniuk was transferred to the village of Rozhniv, and in 1987, to Pistyn, both in Kosiv raion. Throughout this period of his ministry he continued to maintain contacts with dissidents. In 1988 Romaniuk wrote a letter to the metropolitan of Kyiv and Halych, Filaret Denysenko, proposing that, as part of the celebrations of the millennium of the Baptism of Rus’ (see Christianization of Ukraine), a theological academy and a theological seminary with instruction in Ukrainian be opened, that the Bible be published in Ukrainian, and that church-state relations be revised in light of Mikhail Gorbachev’s policies of perestroika.

In July 1988 he received permission to emigrate, and on 27 July he left for Canada with his son, Taras. In December 1988 he was appointed to a parish of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Canada (UOCC) in Waterloo, Ontario. He also visited communities in Canada and the United States of America, giving lectures at UOCC and UAOC parishes. Metropolitan Mstyslav Skrypnyk elevated Romaniuk to the rank of mitred archpriest ‘for his struggle and contribution to the cause of securing the independence of the Ukrainian Orthodox church.’ In November 1989 Romaniuk traveled to Great Britain. At the end of December 1989 he returned to Ukraine and joined the newly revived UAOC there.

On 28 April 1990 in Kosiv Romaniuk was tonsured a monk and elevated to the rank of archimandrite with the monastic name Volodymyr. On 29 April 1990 at the Church of Saints Peter and Paul in the village of Kosmach, Ivano-Frankivsk oblast, he was consecrated bishop of Uzhhorod and Vynohradiv, with the right to serve in eastern Ukraine. From September 1990 he resided in Kyiv and served at the Church of Saint Nicholas Prytyska in the Podil district. On 9 November 1990 he was elected deputy chair of the Kyiv eparchial council of the UAOC. On 29 November 1990 Patriarch Mstyslav Skrypnyk appointed Romaniuk vicar bishop of the Kyiv eparchy with the title of archbishop of Bila Tserkva. From 1991 Romaniuk headed the Mission Department of the UAOC Patriarchal office. On 25–26 June 1992 he participated in the All-Ukrainian Orthodox Council, at which a portion of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Moscow Patriarchate united with a portion of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox church to form the Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Kyiv Patriarchate (UOC-KP).

On 4 November 1992 the prosecutor’s office of Ivano-Frankivsk oblast rehabilitated Romaniuk in connection with his 1972 conviction, and in 1993 he was rehabilitated in connection with his 1946 verdict.

On 17 February 1993 the synod of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Kyiv Patriarchate (UOC-KP) appointed Romaniuk archbishop of Lviv and Sokal, and on 11 June of that year, archbishop of Chernihiv and Sumy. After the death of Patriarch Mstyslav Skrypnyk on 14 June 1993, the synod of the UOC-KP elected Romaniuk patriarchal locum tenens and elevated him to the rank of metropolitan. On 21 October 1993 at the All-Ukrainian Orthodox Council of the UOC-KP in Kyiv, he was elected Patriarch of Kyiv and All Rus’-Ukraine. His enthronement took place on 24 October 1993 in Saint Sophia Cathedral.

In May 1994 Romaniuk suffered another heart attack, which seriously undermined his health. He died in Kyiv on 14 July 1995. Initially, the UOC-KP decided that Patriarch Volodymyr should be buried on the grounds of the Vydubychi Monastery; later, however, the preferred burial site was determined to be the grounds of Saint Sophia Cathedral. The initiators of this change are unknown, but the idea was supported by some politicians, including former president of Ukraine, Leonid Kravchuk. The state authorities, however, proposed burial at Baikove Cemetery, and the deputy prime minister of Ukraine for humanitarian affairs, Ivan Kuras, refused permission for burial at the Saint Sophia Cathedral on the grounds that it is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Despite the refusal, on 18 July 1995, after the funeral service, a procession of clergy, faithful, public figures, and politicians marched with Patriarch Volodymyr’s coffin from Saint Volodymyr's Cathedral toward Saint Sophia Cathedral. En route, militia attempted to block the procession, provoking clashes between law enforcement and members of the nationalist organization UNA-UNSO, who accompanied the cortege. The procession was unable to enter the cathedral grounds, which were closed and surrounded by Berkut special-forces unit. As a result, a grave was hastily dug near the cathedral walls, and the patriarch was buried there. The final stages of the funeral were marked by violent clashes between UNA-UNSO members and special-forces troops who beat a number of mourners. The events of 18 July 1995 entered contemporary Ukrainian history as the ‘Black Tuesday.’

Romaniuk was the author of numerous essays and articles on spirituality, Ukrainian religious tradition, and the history of the Ukrainian church published in both secular and religious periodicals. He was a steadfast advocate for the independence of the Ukrainian Orthodox church and also championed mutual understanding and cooperation between Ukrainian Orthodox and Greek Catholics. A collection of his letters, appeals, essays, and materials related to his case was published in English translation in 1980 in the United States under the title A Voice in the Wilderness.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Sprava № 4509 (Redchuk, Moshenets, Romaniuk, Matvieieva, Rokhmanenko, Shostia), Arkhiv Sluzhby Bezpeky Ukrainy v Ivano-Frankivskii oblasti

Reabilitovani istorieiu: Ivano-Frankivska oblast, bk 2 (Ivano-Frankivsk 2006)

Pashchenko, V. ‘Patriarkh Volodymyr (Vasyl Romaniuk): V"iazen' sovisti, borets' za nezalezhnist' Ukraïny,’ Ridnyi krai no 2 (2009)

Zinchuk, D. Reliihna ta hromads'ko-politychna diialnist' Patriarkha Kyïvs'koho i vsiiei Rusy-Ukraïny Volodymyra (Vasyla Romaniuka) (Ivano-Frankivsk 2009)

Romaniuk, T. Patriarkh Volodymyr, abo spohady pro bat'ka (Kosiv 2019)

Birchak, V. ‘GULAHivs'ka “odisseia” Patriarkha Volodymyra,’ Istorychna Pravda (2 June 2020)

Anatolii Babynskyi

[This article was written in 2025.]

.jpg)