Canada

Canada [Канада]. Federal state, occupying about two-thirds of the North American continent, with an area of 9,976,139 sq km and a population (2020) of 37,754,249. Because of immigration, Canada is a multiethnic society, a fact acknowledged officially in 1971 by the federal government in Ottawa through its policy of multiculturalism within a bilingual (English-French) framework. Canadians of Ukrainian origin numbered 1,359,655 in 2016 (3.87 percent of the total). They formed the ninth-largest group in the country, preceded by the Canadians, English, French, Scots, Irish, Germans, Italians, and Chinese.

Immigration of Ukrainians. Isolated individuals of Ukrainian background may have come to Canada during the War of 1812 as mercenaries in the de Meuron and de Watteville regiments. It is possible that others participated in Russian exploration and colonization on the west coast, came with Mennonite and other German immigrants in the 1870s, or entered Canada from the United States. The mass movement of Ukrainians to Canada, however, occurred later, in a series of distinct waves. The first period, from 1891 to the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, brought approximately 170,000; 68,000 came during the second or interwar period; and 34,000 came in the immediate post-Second World War period between 1947 and 1954. In the 1980s a sizeable number of Ukrainians from Poland and a smaller group from the former Yugoslavia began immigrating to Canada, their numbers being estimated to be at least 10,000 by the end of the decade. They were joined in the 1990s by immigrants from Ukraine. The latter numbered 23,435 in the period from 1991 to 2001, although not all of them were ethnic Ukrainians. Since then immigration from Ukraine has continued at a rate of approximately 2,500 people per annum.

Between 1891 and 1914 most of Canada’s Ukrainian immigrants came from the crown lands (provinces) of Galicia and Bukovyna in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Galicia being the main source. Males predominated (although it was very common for entire families to immigrate), illiteracy was high, and peasant farmers greatly outnumbered other classes. Almost two-thirds gave as their destination the Prairie provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta, where the Canadian government offered homesteads of 160 acres (64.7 ha, or 113 morgs in the land measure the newcomers commonly used) for 10 dollars to induce settlement.

Interest in Ukrainian immigration to Canada was expressed first in Galicia. In 1891 Ivan Pylypow and Wasyl Eleniak, two peasants from Nebyliv, in Kalush county, came to investigate, and Pylypow’s subsequent accounts of free land gave rise in 1892 to the first Ukrainian colony, at Edna-Star, east of Edmonton, Alberta. In 1895 Osyp Oleskiv, an educator and agricultural expert in Lviv, concerned with the economic plight of the Ukrainian peasantry, visited Canada and was impressed with its suitability for the excess rural population of Galicia. His public lectures and two booklets, Pro vil'ni zemli (About Free Lands) and O emigratsiï (About Emigration), did much to stimulate Ukrainian immigration to Canada (see Emigration). The following year Clifford Sifton became minister of the interior in Sir Wilfrid Laurier’s new Liberal administration and, amid much criticism for bringing large numbers of culturally alien people into Canada, began to solicit agricultural immigrants from southern, central, and eastern Europe.

In the years preceding the First World War the number of immigrants coming to Canada from central Ukraine, particularly Right-Bank Ukraine, increased substantially. These were predominantly migrant male laborers who sought work in the industrial regions of Ontario and Quebec. In general, they did not associate with the existing Ukrainian community in Canada, and they commonly did not figure in subsequent census statistics as ‘Ukrainians.’

Ukrainian immigration ceased during the First World War but resumed in the 1920s as stability returned to eastern Europe and the need for labor in Canada grew. The Canadian Immigration Act was amended (1923) to permit former nationals from recent enemy countries to immigrate and in 1925 the Railways Agreement granted the Canadian Pacific Railway and Canadian National Railways the right to seek immigrants from ‘non-preferred’ countries in central and eastern Europe. Galicia and Bukovyna, now part of Poland and Romania respectively, continued to supply the majority of immigrants from Ukraine. Most were generally better educated, more secure financially, and more diverse occupationally than members of the first wave had been. The majority were young, single males, although a substantial number of young, unmarried women (recruited as dometics) also arrived; far, far fewer immigrant families set off to Canada at this time. They came to an established Ukrainian-Canadian community and benefitted from its moral and financial assistance. Canada still favored agriculturalists, and the Prairie provinces again attracted the bulk of the Ukrainian immigrants. After 1929, with widespread unemployment in Canada, few Ukrainians were admitted.

The third wave of Ukrainian immigrants to Canada consisted of persons displaced by the Second World War (see Displaced persons), living mainly in displaced persons camps in Austria and Germany. The newly formed Ukrainian Canadian Committee (later, Ukrainian Canadian Congress) urged the Canadian government to accept Ukrainian immigrants. Western Ukrainians again predominated, but all ethnic Ukrainian territories were represented. Socioeconomically, the new immigrants were more diverse than previous immigrants had been, and greater numbers were well educated. Still, the majority were laborers. A great many settled in urban areas in the industrialized East, particularly in Ontario.

The changing political situation in Poland during the 1980s made emigration a distinct possibility, and approximately 10,000 Ukrainians from that country left for Canada. A very small number of immigrants from Ukraine itself came to Canada during the 1970s and 1980s, mainly Jews and random cases of family reunification. This situation changed considerably in the post-independence period. By the end of the 1990s approximately 2,500 people per annum were immigrating to Canada from Ukraine. The immigrants tended to be well educated professionals. About half of them came from the cities of Kyiv and Lviv (and 26 and 24 percent respectively in one study).

Today over 90 percent of the Ukrainian-Canadian population is native-born.

Population. As subjects of a foreign power and possessing a blurred national identity, the first Ukrainians in Canada appeared under a variety of names, producing permanent confusion in early statistics. It was not until 1921 that a ‘Ukrainian’ designation appeared in the country’s census forms. In 1931 the Canadian census showed 225,133 Ukrainians, or 2.2 percent of the population. In the 1971 census there were 580,660 Ukrainians, or 2.7 percent of the total Canadian population. Ethnic identity in this case was established by paternal lineage. The 1981 census allowed Canadians to declare their origins in either single or multiple terms, the former indicating an exclusive ‘Ukrainian’ origin response and the latter a designation of ‘Ukrainian’ and some other origin. Furthermore, respondents were allowed the option of self-definition rather than to be restricted to a paternal lineage definition. As a result, 529,615 persons indicated their origin as being Ukrainian and 225,360 indicated that it was at least one component in their background. In 1991 the number of Ukrainians in Canada reached 1,054,300 (410,410 single response and 643,890 multiple) and in 2001 it stood at 1,071,060 (326,200 single and 744,860 multiple). In 2016 Canadians of Ukrainian origin numbered 1,359,655 (3.87 percent of the total).

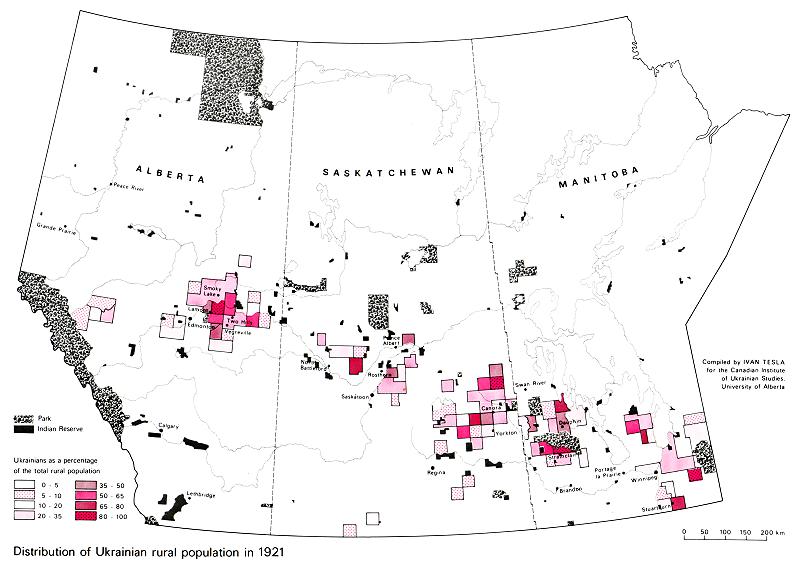

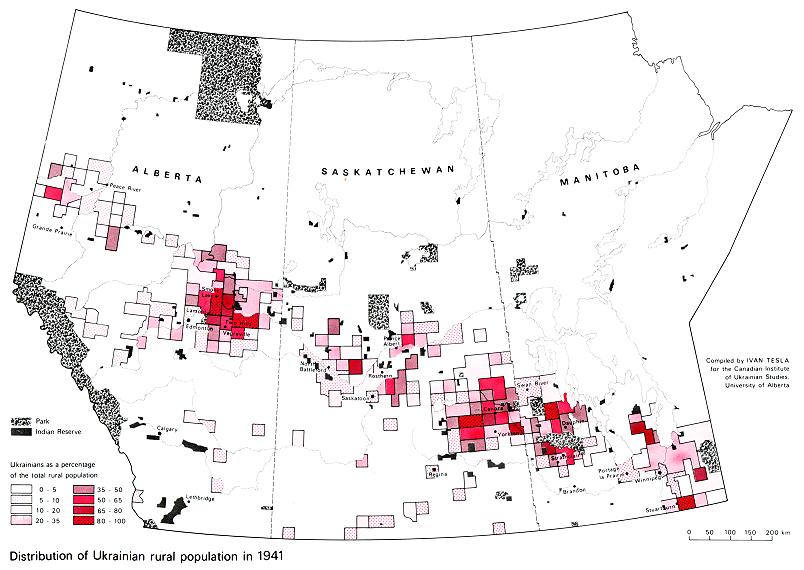

Settlement and distribution. After 1896 the Ukrainian colony at Edna-Star expanded rapidly, becoming the largest Ukrainian settlement in Canada. By 1914 the wooded-prairie parkland of western Canada was marked by a series of well-defined blocs of Ukrainian settlement (commonly refered to as ‘colonies’ at that time) that extended from Alberta through the Rosthern and Yorkton-Canora districts of Saskatchewan to the Dauphin, Interlake, and Stuartburn regions of Manitoba. Most Ukrainian immigrants preferred to settle in the parkland region, which was not considered prime agricultural land, because it offered a mix of meadow and, notably, wood. They also tried to settle close to their fellow countrymen. Canadian immigration officials started to become concerned about the size of some of the bloc Ukrainian settlements and made conscious efforts to try and establish new nodes of settlement so as to limit the expansion of existing Ukrainian ‘colonies.’

In the interwar period secondary blocs, like that in the Peace River region in Alberta, emerged.

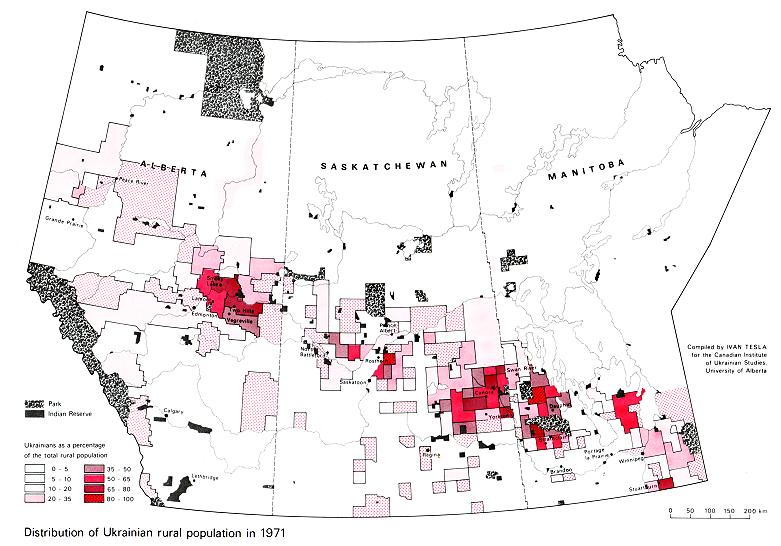

Within the blocs a distinctive way of life evolved around rural crossroads communities that had Ukrainian names and consisted of a post office, general store, church, and community center. The cohesiveness of these crossroad settlements were later undermined by the development of towns along the railroad lines that were built near or through Ukrainian areas. Migration from rural areas to urban centers began in the interwar period and accelerated greatly after the Second World War. Today the physical and cultural identity of the bloc settlements has been transformed by the automobile, the mass media, higher education, farm consolidation, rising standards of living, upward social mobility, and extensive rural depopulation.

Some of the early Ukrainian immigrants in cities were prospective farmers accumulating capital; others became permanent members of the urban labor force. Many of the living areas adjacent to the city core continue to house Ukrainian churches, organizations, and businesses, although the crowded tenements in which Ukrainians once tended to live were generally been replaced by single-family dwellings in working-class districts and later in the suburbs. Immigrants from the second and subsequent immigrations, as well as migrants from the rural blocs, have greatly increased the Ukrainian urban population. In 2001 the most significant urban centers of Ukrainian life in Canada included Edmonton (125,720), Toronto (104,490), and Winnipeg (102,635). (See Table 1.)

In 1931 over 85 percent of all Ukrainians lived in the three Prairie provinces, where 77.9 percent were rural. Rural depopulation and a large outmigration beginning in the latter 1930s changed that situation considerably. By 1971 only 57.8 percent resided on the Prairies, and 75 percent of all Ukrainian Canadians were urban. Prairie Ukrainians, most urban in Alberta (70.2 percent) and least urban in Saskatchewan (53.1 percent), were less urban than those in Ontario (91.1 percent). By 2001 only 52.8 percent of Ukrainian Canadians lived in the Prairie provinces. The most significant gains in terms of the proportional share of the Ukrainian-Canadian population were seen in Ontario, which went from 10.9 percent in 1931 to 27.2 percent in 2001, and British Columbia, which went from 1.1 percent in 1931 to 16.7 percent in 2001 (See Table 2 and Table 3).

Socioeconomic development. Ukrainians initially homesteaded on unbroken land with limited capital, outdated agricultural technology, and no experience with large-scale North American farming. High wheat prices during the First World War brought prosperity, marked by the transition to ox- and horse-power and then to machines as farming became a business. Expansion based on wheat continued to the 1930s, when many farmers who had operated on credit or through mortgages were ruined by low grain prices. Many turned to more stable mixed farming, growing a variety of grains and keeping stock and dairy cattle. Since 1945 the Ukrainian blocs have undergone large-scale mechanization, farm consolidation, and rural depopulation. In 1971, 16,675 of the 23,459 farms with Ukrainian operators on the Prairies were between 240 and 1,119 acres (97.1–452.6 ha) in size.

Early Ukrainian wage earners were either unskilled laborers in Canada’s cities, members of railway gangs and lumbering crews, or miners in the Rocky Mountains, Northern Ontario, Quebec, or on Cape Breton Island. Women worked as domestics or in restaurants and hotels. Unsafe work conditions, low wages, exploitation, and discrimination made radicals of many Ukrainian workers, involving them in labor unrest and unionization, particularly during the 1930s when the unemployed faced public relief or (if unnaturalized) deportation.

Some urban Ukrainians before 1914 became small businessmen, general merchants, and shopkeepers, and catered to the immigrants’ special needs through such establishments as Ukrainian bookstores and boardinghouses. While large-scale movement into the towns and villages of the rural bloc settlements was an interwar and postwar phenomenon, the earlier flour mills, general stores, and implement dealerships run by Ukrainians had laid the foundations. Hotels, bakeries, garages, and construction and transportation companies followed. Teaching was the first profession to attract Ukrainians in large numbers. Agricultural colleges also drew young men anxious to improve farming techniques.

Ukrainian co-operatives first appeared before the First World War. At its height the Ruthenian Farmers’ Elevator Company (1917–30) operated eleven elevators in Manitoba and four in Saskatchewan. Ukrainian consumer co-operatives, which emerged in rural areas in the interwar years, profited from the experiences of interwar immigrants with similar enterprises in Western Ukraine. Alberta and Manitoba had nine consumer co-operatives each, and Saskatchewan had six.

Unlike the co-operatives, Ukrainian credit unions expanded after 1945 because of their popularity among the third wave of immigrants. By the 1970s there were nearly 40, with a membership of approximately 49,000. The largest were the Ukrainian Credit Union in Toronto, the Carpathia Co-operative Credit Union in Winnipeg, and Buduchnist in Toronto. In the 1950s two regional co-ordinating committees were established for Ukrainian credit unions in western and eastern Canada. They merged in the mid-1970s to create the Council of Ukrainian Credit Unions in Canada. In the latter part of the 20th century the number of Ukrainian credit unions in Canada dropped significantly as a large number of them consolidated their operations through mergers with other credit unions (commonly, although not always, Ukrainian). At the same time, however, the larger credit unions expanded the number of their branches through the process of consolidation or by the opening of new branches. As a result, at the start of 2000 there were 14 Ukrainian credit unions in Canada with over 30 branches. Their total membership had grown to over 65,000 and their net assets amounted to approximately CAD 834 million.

Between 1931 and 1971 the percentage of Ukrainians in agriculture dropped from 57.3 to 11.2; in the entire Canadian labor force the percentage decrease was from 28.7 to 5.6. In the same period the number of laborers or unskilled workers in the Ukrainian male labor force dropped from 23.9 to 3.5 percent. Participation in manufacturing, construction, and related occupations increased from 7.8 percent in 1931 to 27.7 percent in 1971, Ukrainians being overrepresented compared to Canadians as a whole. Participation in trade, sales, finance, administrative, and professional occupations increased. By 1971 the number of Ukrainians in medicine, law, and engineering had risen from 0.025 percent in 1931 to 0.23 percent (physicians and surgeons), 0.74 percent (professional engineers), and 0.13 percent (lawyers), but the proportion was still below that of the total Canadian work force in each category. Table 4 shows the distribution of Ukrainian Canadians in various occupations in 1971.

In 1970 the average income of Canadians over 15 years of age was $5,033, compared to $4,636 for Ukrainian Canadians; Ukrainian males earned less than Canadian males, but Ukrainian females earned more than the national average. The socioeconomic position of Ukrainians was lowest in the Prairie provinces and progressively better in Ontario, British Columbia, and Quebec. In 1981, 15.3 percent of single-origin Ukrainian Canadians had attended university, which was slightly below the national level (15.9 percent).

Although the upward mobility of Ukrainian Canadians from peasant origins, rural status, and illiteracy has been impressive, as a group Ukrainians remain entrenched in the Canadian lower middle class.

General history. The First World War greatly intensified anti-Ukrainian feelings in Canada. As subjects of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, unnaturalized immigrants became enemy aliens. Approximately 6,000 Ukrainians were interned, either as Austrian reservists or potential security threats, or for being unemployed. Many were harrassed and fired from their jobs. Those naturalized for less than 15 years were disenfranchised in 1917; in September 1918 newspapers in Ukrainian and other enemy-alien languages were temporarily suspended. In spite of such treatment Ukrainians participated in the Canadian Patriotic Fund, the Red Cross, and the Victory Loan campaigns, and approximately 10,000 men enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

Participation in Canadian political life. In 1908 Ivan Storosczuk was named reeve by the all-Ukrainian council in the municipality of Stuartburn, Manitoba, becoming the first Ukrainian to lead a local government. Where they were numerous, Ukrainians eventually dominated the elected and administrative sections of rural municipalities, school divisions, counties, towns, and villages. Theodore Stefanyk, elected alderman in Winnipeg in 1912, was the first Ukrainian to be successful in urban politics. Since the Second World War such successes have been numerous. William Hawrelak was elected mayor of Edmonton four times between 1951 and 1977, Stephen Juba was mayor of Winnipeg from 1956 to 1977, and Laurence Decore served as mayor of Edmonton from 1983 to 1988.

The first Ukrainian elected to a provincial legislature was Andrew Shandro, Liberal candidate for the predominantly Ukrainian riding of Whitford in the 1913 Alberta election. He was followed by Taras Ferley, who became the Liberal member for Gimli, Manitoba, in 1915. By 1975, 77 Ukrainian candidates had been successful in Manitoba, 68 in Alberta, and 37 in Saskatchewan; Ontario and British Columbia, where Ukrainian candidates did not appear until the 1940s, had elected 15 and 1 respectively. Since that time not only have more Ukrainians have been elected to provincial legislatures, but in some cases they have served as provincial premiers (Roy Romanow in Saskatchewan in 1991–2001 and Ed Stelmach in Alberta in 2006–11).

The first Ukrainian in the House of Commons in Ottawa was Michael Luchkovich, who represented the Vegreville constituency for the United Farmers of Alberta (1926–35). By 1975, 62 Ukrainians had won federal seats—25 in Alberta, 15 in Manitoba, 13 in Ontario, and 9 in Saskatchewan—the majority representing the Progressive Conservative party. Only after 1945 did Ukrainian candidates make noticeable progress in the Liberal and Conservative parties or outside the Ukrainian bloc settlements. Many early candidates represented Canadian protest parties. Generally, Ukrainian-Canadian candidates have been overwhelmingly from the first and second immigrations.

Cabinet posts have come to Ukrainian Canadians since the Second World War. Federally, Michael Starr (Starchevsky) served as Conservative minister of labor (1958–63) under John Diefenbaker; Norman Cafik held the multiculturalism portfolio (1977–9) in Pierre Trudeau’s Liberal administration; and (Ray) Ramon Hnatyshyn and Steve Paproski were ministers in the short-lived Conservative cabinet of Joe Clark in 1979–80. In Brian Mulroney’s administration Hnatyshyn served as government house leader and minister of justice, while Paproski was the deputy speaker of the House of Commons. Hnatyshyn later (1990–5) served as Governor General of Canada.

Ukrainians have been better represented provincially. In Alberta Ambrose Holowach and Albert Ludwig served as Social Credit ministers, and in the 1970s and 1980s Wasyl Diachuk, Albert Hohol, Julian Koziak, George Topolnisky, Peter Trynchy, and William Yurko sat in Conservative cabinets. In 1993 Gene Zwozdesky obtained his first Cabinet appointment, while in 2006 Ray Danyluk joined the Cabinet as Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing. Laurence Decore led the Liberal Party of Alberta from 1988 to 1993. Ed Stelmach was head of the Alberta Progressive Conservative Party and, by that fact, premier of the province in 2006–11. In Manitoba, Liberal premier Douglas Campbell appointed the first Ukrainian cabinet ministers, Nicholas Bachynsky and Michael Hryhorczuk, in the 1950s; Samuel Uskiw, Ben Hanuschak, Peter Burtniak, and Bill Uruski served in Ed Schreyer’s New Democratic government (1969–77). The cabinets of Premier Gary Filmon (1988–99), himself of mixed Polish-Ukrainian background, included four people of Ukrainian origin. Likewise, Ukrainians have been included in the NDP cabinets of Gary Doer (1999–2009). Three Ukrainian cabinet ministers in Saskatchewan—Alex Gordon Kuziak, John Kowalchuk, and Roy Romanow—represented the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation under Tommy Douglas (1952–64) and its successor, the New Democratic party (NDP), under Allan Blakeney in the 1970s and 1980s. Romanow later went on to head the NDP and served as premier of Saskatchewan in 1991–2001. Myron Kowalsky served as Government Whip in the province before being elected as Speaker of the Legislative Asssembly in 2001 (and re-elected in 2004). Progressive Conservative John Yaremko has been the sole Ukrainian cabinet minister in Ontario.

Canadians of Ukrainian origin summoned to the Senate of Canada include William Wall (Volokhatiuk) (Manitoba, 1955–62), John Hnatyshyn (Saskatchewan, 1959–67), Paul Yuzyk (Manitoba, 1963–86), John Ewasew (Quebec, 1976–8), Martha Palamarek Bielish (Alberta, 1979–90), Raynell Andreychuk (Saskatchewan, 1993–2019) and Dave Tkachuk (Saskatchewan, 1993–2020). Stephen Worobetz served as Saskatchewan’s Lieutenant Governor in 1969–75, as did Sylvia Fedoruk in 1988–94. Peter Liba was Manitoba’s Lieutenant Governor in 1999–2004.

For many years Ukrainians supported the Liberal party, which was in power when they first arrived. Together with other Canadians from the lower socioeconomic strata, Ukrainians have shown considerable support for Canadian protest parties, which emerged in the 1930s—the Social Credit party and the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (subsequently the New Democratic party). From the 1920s to the 1940s Ukrainians, Jews, and Finns were the most prominent ethnic groups in the Communist Party of Canada. In the late 1950s many Ukrainians turned to the Progressive Conservative party, approving John Diefenbaker’s anticommunism and his appointment of the first Ukrainian Canadian to the federal cabinet. Increasingly, the voting habits of Ukrainians reflect their economic class or region rather than any common ethnic pattern.

Religion. No Ukrainian Catholic or Orthodox priests accompanied the earliest Ukrainian immigrants to Canada. Among the denominations that moved to fill the spiritual vacuum were the Methodists and Presbyterians, the Russian Orthodox church and the Roman Catholic church.

A unique religious experiment originated with a Russian Orthodox priest, Stefan Ustvolsky. A self-proclaimed bishop and metropolitan of the Orthodox Russian church for America who went by the monastic name Seraphim, he arrived in Canada in 1903 at the behest of several early community leaders and began to ordain priests. In 1904, alarmed by Seraphim’s growing eccentricities, several priests, led by Ivan Bodrug, broke with him and formed the Independent Greek church. The new church retained the Eastern rite and liturgy but was supervised and financially supported by the Presbyterian church, with which Bodrug had contacts. At its height, the Independent Greek church claimed 60,000 adherents. It declined after 1907 when Presbyterian pressure forced genuine Protestant reform; it became part of the Presbyterian church and then of the United Church of Canada. Bodrug remained within the Ukrainian evangelical movement, working closely with the Ukrainian Evangelical Alliance in North America (est 1922). In 1931, 1.6 percent of Ukrainian Canadians were United church adherents. By 1971 intermarriage and assimilation had increased the figure to 13.9 percent (11.9 percent in 1981), the fourth-largest religious denomination among Ukrainian Canadians.

Bukovynian immigrants who appealed to the Orthodox church in Bukovyna for priests were directed to the Russian Orthodox mission in the United States. The Russian Orthodox missionaries who came were also popular among Galicians. They used a familiar form of worship, charged little, and gave the laity considerable local control. The Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic church declined sharply after 1917 when the Russian Holy Synod’s financial support for missionary work ended and the traditional Ukrainian churches were re-established in Canada. Today the Russian Orthodox faith claims a few hundred Ukrainian-Canadian adherents. Parishes that recognize the patriarch of Moscow share a bishop with their American counterparts. A few Orthodox Ukrainians belong to the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of America, with its seat in the United States, and a number are affiliated with the Orthodox Church in America.

A small number of Ukrainian Baptists (Stundists) from the Russian Empire immigrated to Canada prior to 1917 to escape religious persecution. They were first associated with the Russian Stundists, but in 1921, under Peter Kindrat, separate Ukrainian congregations were organized. In 1946 the Ukrainian Bible Institute opened in Saskatoon to train Ukrainian Baptist clergy and to publish religious literature. The Ukrainian Evangelical Baptist Union of Canada, strengthened by the third immigration, had approximately 25 congregations in 1971. Their members, together with those Ukrainians in other Baptist congregations, accounted for 1.4 percent of all Ukrainian Canadians at that time. The Lutheran church, the Pentecostal Assembly, the Seventh-Day Adventists, and the Jehovah’s Witnesses also have significant Ukrainian memberships but are marginal to the organized Ukrainian community. Publications and religious programming in Ukrainian acknowledge the Ukrainian components. Only a minority of Ukrainian Protestants form independent congregations.

The two major Ukrainian denominations in Canada have been the Ukrainian Catholic church and the Ukrainian Orthodox church, which were supported by 58.0 and 24.6 percent respectively of all Ukrainian Canadians in 1931. Despite strained relations between them, the two churches have been central in preserving the Ukrainian language, culture, and identity. Since the 1940s their strength has declined. In 1971 the Ukrainian Catholics constituted 32.1 percent and the Orthodox 20.1 percent of the Ukrainian-Canadian population, while in 2001—albeit with a different measure of the sample group—they constituted 11.8 percent (126,200) and 3.1 percent (32,720) respectively.

The first Ukrainian Catholic immigrants were visited periodically by priests from Pennsylvania, notably Nestor Dmytriv, as early as 1897. Immigrants and itinerant priests came under the jurisdiction of the French-dominated Roman Catholic hierarchy in western Canada, which tried to absorb the Ukrainians. In view of Ukrainian opposition, the Roman Catholic church gradually accepted the idea of a separate Ukrainian Catholic hierarchy and worked to obtain clerical personnel. Then for approximately a generation the Roman Catholic church strongly assisted its Ukrainian counterpart, particularly in the establishment of schools and newspapers.

Because a papal decree of 1894 imposed celibacy on Ukrainian Catholic priests in North America, the secular clergy, who vastly outnumbered the regular clergy in Galicia, could not work in Canada. Accordingly, the first regular Ukrainian religious presence in Canada consisted of a group of Ukrainian monks, members of the Basilian monastic order, and four nuns of the Sisters Servants of Mary Immaculate, who were sent to Canada by Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky. From Beaverlake (now Mundare) in Alberta they served a pastoral community scattered over hundreds of kilometers. To fill the vacuum in Saskatchewan, Belgian missionaries, some of whom adopted the Eastern rite, began to serve among the Ukrainians. Most notable in this regard was Achille Delaere of the Redemptorist Fathers, who was based at Yorkton, Saskatchewan. Because of Delaere’s work, an Eastern-rite branch of the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer was founded in Galicia in 1913 and later in Canada.

Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky toured the Ukrainian settlements in 1910, and in 1911 he successfully appealed to Rome for a Ukrainian Catholic bishop. In December 1912 Nykyta Budka became the first bishop of the Ruthenian Greek Catholic church in Canada, incorporated by Canadian charter in 1913. He was not under the Roman Catholic hierarchy but directly responsible to the apostolic delegate in Canada. In the course of trying to restore the church’s customary dominance in Ukrainian life, Budka alienated many Ukrainians, particularly the influential and growing intelligentsia. The ensuing conflict between them set in course the events leading to the formation of the Ukrainian Greek Orthodox Church of Canada in 1918. Over a decade of strong confessional strife followed.

Despite Orthodox inroads, the Ukrainian Catholic church expanded in the 1920s and by 1931 had 100 priests, 58 of them secular, serving 350 parishes (3 in British Columbia, 102 in Alberta, 108 in Saskatchewan, 110 in Manitoba, 21 in Ontario, 5 in Quebec, and 1 in Nova Scotia). Budka returned to Europe in 1927. He was succeeded in 1929 by Vasyl Ladyka, who provided the church with stronger leadership. In 1948 three exarchates were created: the eastern (Toronto) under Bishop Isidore Borecky, the western (Edmonton) under Bishop Nil Savaryn, and the central (Winnipeg) under Ladyka, who was elevated to titular archbishop. In 1951 Saskatchewan exarchate was carved out of the western exarchate, with Andrew Roborecki as bishop. In 1956 Pope Pius XII established Ukrainian Catholic metropoly in Canada, elevating the four exarchates to eparchies with the central as the archeparchy. Maksym Hermaniuk became the first metropolitan. In 1974 the eparchy of New Westminster for British Columbia, under Bishop Isidore Chimy, was created from parts of Edmonton eparchy. Presently the Ukrainian Catholic church in Canada is headed by Metropolitan Lawrence Huculak in conjunction with bishops Kenneth Nowakowski (New Westminster), David Motiuk (Edmonton), Michael Wiwchar (Saskatoon) and Stephen Chmilar (Toronto).

During the 1970s, in the 600 Ukrainian Catholic parishes and missions, the secular clergy greatly outnumbered their monastic counterparts. After the Second World War married priests in the third immigration were permitted by the Vatican to serve, although ordination of married men by Canadian Ukrainian Catholic bishops was generally forbidden. In 1970 the Basilian monastic order had 109 monks, including 51 regular priests. The order became a separate Canadian province in 1948 and has its seat in Winnipeg, its publishing house in Toronto, and its rich library, archives, and museum in Mundare. The Ukrainian Redemptorist Mission in Canada, a separate province after 1961, had over 60 regular priests in the 1970s. The provincial seat is in Winnipeg. For many years the order maintained a minor seminary for boys is in Roblin, Manitoba (Saint Vladimir’s College ) and a publishing house is in Yorkton, Saskatchewan. Until the 1970s the Eastern-rite Brothers of the Christian Schools operated Saint Joseph’s College (est 1919) in Yorkton. A small number of Ukrainian Studite monks, who came to Canada in 1951, live at Woodstock, Ontario. There are approximately 300 Ukrainian Catholic nuns in Canada. The Sisters Servants of Mary Immaculate have operated schools, orphanages, hospitals, and, more recently, senior-citizens’ homes. Their private schools, under provincial regulations, include or have included Sacred Heart Academy in Yorkton, Immaculate Heart School (est 1905 as the Ukrainian Catholic School of Saint Nicholas) in Winnipeg, and Mount Mary Immaculate Academy (1952–1970) in Ancaster, Ontario, which housed the novitiate after being moved from Mundare in 1946. Two minor orders are the Sisters of Saint Joseph in Saskatoon eparchy and the Missionary Sisters of Christian Charity in Toronto eparchy.

Ukrainian Catholic religious training and education in Canada is centered in Ottawa, the site of the Holy Spirit Seminary (est 1980) and the Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky Institute of Eastern Christian Studies (moved to Ottawa in 1990, and subsequently moved to Toronto in 2017).

Since the 1930s the Ukrainian Catholic church has sponsored national men’s, women’s, and youth lay organizations with local branches, and a host of other associations, co-ordinated by a Ukrainian Catholic council in each eparchy and a conciliar superstructure, the All-Canadian Ukrainian Catholic Council—the whole assisted by an active press.

The Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Canada coalesced around the country’s rising Ukrainian intelligentsia, many of them bilingual teachers who had been influenced by the anticlericalism of the Ukrainian Radical party in Galicia. They sharply criticized Bishop Nykyta Budka and condemned the episcopal incorporation of church property, the imposed celibacy, and the use of non-Ukrainian Latin-rite priests. In 1916 Ukrainians on the Prairies established in Saskatoon a nondenominational, nonpartisan Ukrainian students’ residence or bursa, the Mohyla Ukrainian Institute, which they refused to incorporate with the bishop. The ensuing controversy peaked in 1918 when a group associated with the Mohyla Institute broke with Budka and created a Ukrainian Greek Orthodox Brotherhood to establish the Ukrainian Greek Orthodox Church of Canada. Rising national consciousness because of events in Ukraine favored an independent Ukrainian national church in Canada.

The Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Canada has followed the dogma and rites of Orthodoxy. Priests are (usually) married, church property belongs to the congregations, bishops are elected by a council of clergy and laymen, and congregations engage and discharge priests. Theological classes, begun in Saskatoon in 1919, graduated the first priests in 1920; in 1932 the theological seminary moved to Winnipeg, and since 1946 it has been at Saint Andrew's College. The new church attracted many Greek Catholics, Orthodox Bukovynians, and adherents of the Independent Greek and Russian Orthodox churches and by 1935 had 180 parishes and missions (53 in Alberta, 76 in Saskatchewan, 43 in Manitoba, 7 in Ontario, and 1 in Quebec).

For several decades the new church warded off charges of canonical unorthodoxy in its search for autocephaly and a suitable bishop. In 1919 it was taken under the spiritual wing of Metropolitan Germanos (Segedi) of the Antiochian Orthodox church in the United States. In 1924 Archbishop Ivan Teodorovych of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox church in Ukraine and new head of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church in the USA became bishop, but his efforts to be reconsecrated forced him to resign in 1947. Archbishop Mstyslav Skrypnyk replaced him, but his role in Teodorovych’s reconsecration and his overtures towards union with the American Ukrainian church led to his resignation in 1950. In 1951 the second extraordinary sobor voted to make the Ukrainian Greek Orthodox church truly autocephalous through a metropoly with three bishops. Ivan Ohiienko was elected metropolitan, a position he held until his death in 1972, when he was succeeded by Archbishop Mykhail Khoroshy, who was followed by Archbishop Andrei Metiuk in 1975, Wasyl Fedak in 1985, John Stinka in 2006, and Yurij Kalischuk in 2010. In 1990 the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Canada gained eucharistic union with the Patriarch of Constantinople. This move seemingly resolved the lingering issue of canonical legitimacy, but at the same time provoked some resentment among church adherants (particularly after Independence afforded a revival of the Ukrainian Orthodox church in Ukraine).

Three Orthodox eparchies were created in 1951. The eastern eparchy (Toronto) was under Mykhail Khoroshy until 1977 and then under Bishop Mykola Debryn. The western eparchy (Edmonton) took in Alberta and British Columbia and received its first bishop, Andrei Metiuk, in 1959. The central eparchy (Winnipeg) covered Saskatchewan and Manitoba. In 1963 it received an auxiliary bishop, Borys Yakovkevych, with his see in Saskatoon; in 1975 he became head of the western eparchy and archbishop of Edmonton. Bishop Wasyl Fedak replaced him as auxiliary bishop of Saskatoon and the central eparchy in 1978 and in 1981 was given temporary responsibility for the eastern eparchy following Debryn’s death.

The Ukrainian Greek Orthodox Church of Canada also (indirectly) sponsors national men’s, women’s, and youth lay organizations and maintains four institutes with educational facilities (in Edmonton, Saskatoon, Winnipeg, and Toronto) as well as an active press. In 1958 it had 300 parishes and missions with 80 priests; during the 1970s, 100 priests served the same number of parishes.

The two traditional Ukrainian churches have lost considerable ground with Ukrainian Canadians (see Table 5), many estranged by intermarriage, loss of the Ukrainian language, and the adoption of middle-class values and ambitions. In fact, the traditional churches now serve only a minority of Ukrainian Canadians. The Ukrainian Catholic church has responded to decreased affiliation by allowing parishes to adopt the Gregorian calendar and to use English for parts of the liturgy and sermon. Both churches face uncertain futures.

Education and cultural life. The first secular organizations were local reading halls (chytalni), Prosvita societies, and people's homes (narodni domy—community centers or national halls) based on models developed in Galicia and Bukovyna. By 1925 there were approximately 250 of these organizations across Canada. Although most had a specific religious or political orientation and were later often absorbed by national organizations, they offered similar programs: concerts, theater performances, readings for the illiterate, and popular and scholarly lectures, all combining a lively interest in the homeland with instruction about life in Canada. The people's homes and related institutions peaked in the 1930s and declined after the Second World War.

At the end of the 19th century Anglo-Canadians judged immigrants by their distance from British cultural standards and placed great emphasis on assimilating Ukrainian peasants through the public schools and the Protestant churches. Departments of education found it difficult to establish schools in the poor, scattered, and ethnically diverse pioneer prairie communities, however. The education of Ukrainians was further complicated by Manitoba’s 1897 law that permitted instruction in English and any other language when requested by 10 or more students in a school district. The Ruthenian Training School opened in Winnipeg in 1905 (it moved to Brandon two years later) to provide bilingual teachers. Bilingual schools operated unofficially in Saskatchewan and to a lesser extent in Alberta. Led by a nationally conscious leadership, composed largely of bilingual teachers, Ukrainians strongly supported the bilingual schools that the Anglo-Canadians opposed. In 1916 Manitoba repealed its bilingual clause, and Ukrainians turned to private educational institutions to preserve their language and culture.

Ridni shkoly, or part-time Ukrainian schools, existed from the early days of settlement and grew rapidly after the abolition of bilingual public schools. Interwar and post-Second World War immigrants provided new teachers and pupils. In 1958 there were 600 ridni shkoly (almost two-thirds in Ukrainian Catholic parishes), with 650 teachers and 18,000 pupils. By the early 1980s they reached about 9,000 of an estimated 95,000 school-age children. In 1981, 510 teachers taught in 110 ridni shkoly, mainly in urban areas where the post-1945 immigration settled. Some catered to children who speak only English. Most operated at the elementary level, teaching Ukrainian language, culture, and the history of Ukraine; the major cities also offered more advanced courses (kursy ukrainoznavstva). Too few professional teachers and resistance to a common curriculum and central co-ordination created duplication and inconsistent quality. There have been various efforts to co-ordinate ridni shkoly, both within the different organizations and across partisan lines. In 1971 the Ukrainian Canadian Committee formed the Ukrainian National Educational Council of Canada to establish standards, but results have been meager. The existing ridni shkoly also faced a new challenge with students from the fourth wave of immigration, whose Ukrainian-language skills were generally considerably more advanced than those those of Canadian-born students.

Pioneer student residences or bursas emerged in cities and larger towns in the Prairie provinces to provide a Ukrainian environment for rural students completing elementary school. They included the Ukrainska Bursa, which the Independent Greek church opened in Edmonton in 1912; the Adam Kotsko Bursa (1915–17) in Winnipeg; the Metropolitan Sheptytsky Bursa (1917–24) in neighboring Saint Boniface; the Catholic-supported Shevchenko Institute (1918–22) of the Narodnyi Dim Association in Edmonton; and the Shevchenko Institute (1917–19) in Vegreville, which merged with the Hrushevsky Institute (est 1918) in Edmonton. The latter, now Saint John's Institute, and the Mohyla Ukrainian Institute (est 1916) in Saskatoon still exist; along with Saint Andrew's College (est 1946) in Winnipeg and the Saint Vladimir Institute (inc 1961) in Toronto, they are affiliated with the Ukrainian Orthodox church.

Early bursa students, determined to raise the people’s educational level and national consciousness, were the community’s first political and cultural leaders. Today the four Orthodox institutes still work closely with the community, but they are primarily student residences, often with many non-Ukrainian and non-Orthodox members. Saint Andrew's College is an affiliate of the University of Manitoba and offers theology and other courses leading to the bachelor of arts degree. In 1981 its Centre for Ukrainian Canadian Studies became an integral part of the university. The Sheptytsky Institute in Saskatoon (est 1934 as the Markiian Shashkevych Bursa) serves primarily as a Ukrainian Catholic student residence at the University of Saskatchewan.

Ukrainian Canadians have sought public support for their language and culture through a policy of multiculturalism. In the 1950s and 1960s governments on the Prairies accredited Ukrainian as an option, first in high school, then in the elementary grades. In 1971 Edmonton’s Ukrainian Professional and Business Club convinced the Alberta government to amend the School Act to permit bilingual instruction. Pressed by Ukrainians, Saskatchewan legislated similar instruction in 1974 and Manitoba in 1978. Today English-Ukrainian bilingual education from the elementary to the senior high level is available in all three provinces.

Ukrainian language and literature became university subjects after 1945 as Slavic studies departments were established on several Canadian campuses; courses in Ukrainian history, political science, and Ukrainians in Canada followed (see ‘Scholarship’ below).

Civic and political organizations. By the outbreak of the First World War a number of discernable groups (or ‘camps,’ in the contemporary nomenclature) had established themselves among Ukrainians in Canada. They took on a more concrete organizational form in the interwar era, when they were joined by associations created by the more recent arrivals. New groups were also established by immigrants who came after the Second World War. By the 1960s, however, the ranks of the older groups were starting to thin out, and by the 1980s they were fading noticeably. In that same period a smaller number of activity-based Ukrainian societies had established themselves.The newer Ukrainian immigrants who started arriving in the 1980s from Poland and the from Ukraine itself in the 1990s have tended to establish informal groups and partake of community events in a limited way. In some cases they have established local societies for themselves, in other instances, they have joined existing societies virtually as a bloc. They have not, however, set up any national structures.

The socialists were the first Ukrainian group with a national profile. In 1907 Ukrainian branches of the Socialist Party of Canada were formed, and by 1909 approximately 10 existed in centers where workers had reading clubs. The Federation of Ukrainian Social Democrats in Canada (FUSD) was launched in Winnipeg in 1909 and the following year affiliated with the Social Democratic Party of Canada. Ukrainian socialists in Edmonton unsuccessfully challenged the FUSD and Winnipeg leadership in 1910–12, organizing the Federation of Ukrainian Socialists in Canada as an autonomous body within the Socialist Party of Canada. In 1914 the FUSD was renamed the Ukrainian Social Democratic Party of Canada. By 1917 it had become Marxist, and in September 1918, when it was banned by the Canadian government. It was pro-Bolshevik, with 2,000 members.

Other groups also emerged in this period. The most notable was a national populist bloc that coalesced around the newspaper Ukraïns’kyi holos. It included much of the Ukrainian-Canadian intelligentsia and would go on to establish the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Canada in 1918. The largest group in terms of numbers were the Ukrainian Catholics, although they severely lacked capable leaders. There was as well a small group of Ukrainian-Canadian Protestants, who wielded an influence far beyond their numbers.

The First World War and Ukraine’s struggle for independence (1917–20) spurred Ukrainians in Canada to organize on behalf of their countrymen. In 1919 the Ukrainian Canadian Citizens' League, led by supporters of the new Ukrainian Greek Orthodox church, and a Catholic counterbody, the Ukrainian National Council (Winnipeg), sought to help the new Ukrainian republic at the Paris Peace Conference. The Ukrainian Red Cross in Canada was organized to aid war victims in Ukraine, and in 1920 a Ukrainian Central Committee was established to co-ordinate collections for overseas relief. Saint Raphael’s Ukrainian Immigrants’ Welfare Association of Canada, which functioned for approximately a decade after its establishment in 1925, assisted interwar immigrants to Canada.

National organizations emerged in the interwar years. The left resurfaced in 1920, incorporating in 1924 as the Ukrainian Labour-Farmer Temple Association (ULFTA); sections for women (est 1922) and youth (est 1926) followed. As well, the ULFTA created a society to assist the ‘liberation movement’ in Western Ukraine. The ULFTA was the largest ethnic organization sympathetic to the Communist Party of Canada, and its educational and cultural attractions and economic program enjoyed wide support during the Depression. The Ukrainian Self-Reliance League, organized in 1927 by the Ukrainian Orthodox laity, encompassed the following organizations: the Ukrainian Self-Reliance Association, the Ukrainian Women's Association of Canada (est 1926), the Canadian Ukrainian Youth Association (est 1931), and the Union of Ukrainian Community Centres of Canada, which united local Orthodox people's homes and Prosvita societies. The Ukrainian Catholic Brotherhood of Canada was established in 1932 for Ukrainian Catholic laymen, followed in 1944 by the Ukrainian Catholic Women's League of Canada and in 1939 by the Ukrainian Catholic Youth.

Interwar immigrants introduced a number of new organizations. The paramilitary sporting Sitch (renamed the Canadian Sitch Organization in 1928) was founded in 1924 with support from the Ukrainian Catholic church. The church later withdrew its support, and the Sitch declined. In 1934 it was reorganized as the United Hetman Organization, a conservative monarchist movement that favored Pavlo Skoropadsky as hetman of Ukraine. After the death of his son, Danylo Skoropadsky, in 1957 the movement, never too popular but nonetheless influential, rapidly declined. In 1928 the republican-minded veterans of the Ukrainian independence struggle formed the Ukrainian War Veterans’ Association of Canada (UWVA). In 1932 it provided the base for the Ukrainian National Federation, which espoused the militant nationalism of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists. The Ukrainian Women's Organization of Canada, initially associated with the UWVA, affiliated with the Ukrainian National Federation in 1934, the same year that the Ukrainian National Youth Federation of Canada was formed. In the late 1920s the émigré Ukrainian Party of Socialist Revolutionaries, in alliance with the Ukrainian National Home Association in Winnipeg, brought Mykyta Mandryka to Canada as an organizer. He had limited success, and the onset of the Depression brought an end to his efforts.

The institutions of the second immigration generally fared better in urban centers, where the new arrivals were more closely congregated, than in previously settled rural areas.

During the 1930s there was considerable friction between the Canadian-oriented Ukrainian Catholic Brotherhood of Canada and Ukrainian Self-Reliance League and such Ukraine-oriented organizations as the Ukrainian National Federation. In spite of rivalries, Ukrainian-Canadian organizations gave moral and financial assistance to Ukrainian émigré centers in Western Europe and to Ukrainian veterans, war orphans, and numerous causes in Poland and neighboring countries. In the 1930s Polish pacification in Western Ukraine and Stalinist terror in the Soviet Union were widely publicized. The ULFTA, which extolled the Ukrainian SSR and especially its cultural flowering in the 1920s, failed to question Joseph Stalin’s purges, forced collectivization, and the Famine-Genocide of 1932–3. In 1935 an anti-Soviet faction under Danylo Lobai broke away over these issues as well as dissatisfaction with the domination of the Communist Party of Canada over its Ukrainian comrades and formed the Federation of Ukrainian Worker-Farmer Organizations (later the Alliance of Ukrainian Organizations [1936–40] and then the Ukrainian Workers’ League). The ULFTA, banned in 1940, re-emerged as the Association of Canadian Ukrainians after the USSR became Canada’s wartime ally. Its successor, the Association of United Ukrainian Canadians (AUUC), was incorporated in 1946; but with the cold war, the anticommunism of the third immigration, and the decreasing social isolation and poverty of Ukrainian Canadians, it has never had the strength of its predecessor.

In 1940, to unite Ukrainian Canadians behind the war effort, the major non-Communist organizations formed an ad hoc body, the Ukrainian Canadian Congress (at that time, ‘Committee,’ UCC), by merging two smaller committees: the Representative Committee of Ukrainian Canadians (comprising the Ukrainian Catholic Brotherhood of Canada and the Ukrainian National Federation) and the Ukrainian Central Committee of Canada (comprising the Ukrainian Self-Reliance League, the United Hetman Organization, and the Ukrainian Workers’ League). The UCC encouraged military enlistment and participation in victory-loan campaigns, established the Ukrainian Canadian Relief Fund to co-operate with the Red Cross in providing aid to Ukrainian refugees, and from 1945 to 1951 financially supported the Central Ukrainian Relief Bureau in London, England.

The UCC was retained after the Second World War as a permanent co-ordinating superstructure for all non-Communist organizations, which in 1982 numbered between 25 and 30. Six—the Ukrainian Self-Reliance League, Ukrainian National Federation, Ukrainian Canadian Professional and Business Federation, Ukrainian Catholic Brotherhood of Canada, Ukrainian Canadian Veterans’ Association, and Canadian League for Ukraine's Liberation—dominated the body for many years. In 1944 the Ukrainian Canadian Women's Committee was formed to co-ordinate the major national women’s organizations and local unaffiliated groups, traditionally concerned with education, arts and crafts, museums, child-rearing, and language preservation.

The Ukrainian Canadian Servicemen's Association became the Ukrainian Canadian Veterans’ Association in 1945 and was accepted as a founding member of the UCC; its members belong to Ukrainian branches of the Royal Canadian Legion. The Ukrainian Canadian Relief Fund formed the nucleus of the postwar Ukrainian Canadian Social Services. In 1953 the Ukrainian Canadian Students’ Union (SUSK) superseded several smaller predecessors, although not all Ukrainian student clubs on university campuses joined. In the 1970s and early 1980s the Ukrainian Canadian Professional and Business Federation, formed in 1965 by several independent clubs, had a high political profile as a successful lobby.

Organizations introduced by the third wave of immigration attracted few Ukrainian Canadians from the first two immigrations. The Canadian League for Ukraine's Liberation (est 1949), associated with the OUN (Bandera faction), is the largest; tied to it is the Ukrainian Youth Association of Canada, the largest youth group in Canada today. The Plast Ukrainian Youth Association (est 1948) is a Ukrainian boy scout-girl guide group; the Ukrainian Democratic Youth Association (est 1950) enrolled children of postwar immigrants primarily from central and eastern Ukraine. Youth groups generally transmit the principles of the elders as well as entertain. The Ukrainian National Democratic League was formed in 1952 by participants in the struggle for independence (1917–20) and post-1945 immigrants from central Ukraine. A number of veterans’ organizations appeared among the third wave of immigrants, and since 1964 their members have been able to join the Ukrainian Canadian Veterans’ Association. Two scholarly associations, the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences (Winnipeg) and the Shevchenko Scientific Society (Toronto), were established in 1948 and 1949 respectively. There were also professional organizations for doctors, lawyers, engineers, writers, and journalists, supported mainly by the third immigration.

Three Ukrainian mutual-benefit associations, incorporated under the Canada Insurance Companies Act, provide life insurance, funeral benefits, and other services. The oldest, the Ukrainian Mutual Benefit Association of Saint Nicholas (est 1905), is Ukrainian Catholic. The independent Ukrainian Fraternal Society of Canada was formed in 1921. The Workers' Benevolent Association, organized by the Ukrainian Labour-Farmer Temple Association in 1922, served supporters of the Association of United Ukrainian Canadians until it ceased operations at the end of 2006. The Ukrainian National Association and the Ukrainian Fraternal Association in the United States also serve Ukrainians in Canada.

Since the 1970s there has been a growth in the number of dance troupes and (not uncommonly) related Ukrainian cultural societies in Canada. These generally tend to have a non-denominational character. The fourth wave, by and large, has not set out to establish its own distinctive structures or to take over existing Ukrainian groups (as is common in the United States, where their numbers are generally higher and proportionally greater than in Canada).

The press. The oldest Ukrainian newspaper in Canada was the independent weekly Kanadiis’kyi farmer, launched in 1903 with Liberal party support. Ukraïns’kyi holos, begun in 1910 by the bilingual teachers, was influential in the birth of the Ukrainian Greek Orthodox Church of Canada and became the unofficial organ of the Ukrainian Self-Reliance League. In October 1981 the two pioneer newspapers amalgamated.

By the 1920s Ukrainians had published 54 newspapers and periodicals, some lasting a few issues and others for several years. Another 150 appeared between 1921 and 1940, and approximately 350 under the stimulus of the third wave of immigration. Most have been local, non-professional publications; only a few have been large-scale enterprises with a national readership. Winnipeg has traditionally dominated publishing, Toronto and to a lesser extent Edmonton being the main challengers. Saskatoon, Mundare, and Yorkton have been the most significant smaller publishing centers.

The left-wing press began with Chervonyi prapor (Winnipeg) (1907–8), which was succeeded by Robochyi narod (1909–18), as the organ of the Federation of Ukrainian Social Democrats in Canada and the Ukrainian Social Democratic Party of Canada. The Federation of Ukrainian Socialists in Canada published Nova hromada (Edmonton) (1911–12). Ukraïns’ki robitnychi visti (1919–37) was the official organ of the Ukrainian Labour-Farmer Temple Association until replaced by Narodna hazeta (1937–40). The ULFTA also published the newspaper Farmers’ke zhyttia (1925–40) and the magazines Holos robitnytsi (1923–4), Robitnytsia (1924–37), Svit molodi (1927–30), and Boiova molod’ (1930–2). Danylo Lobai’s splinter group sponsored the newspaper Pravda (Winnipeg) (1936–8) and Vpered (1938–40), and Ukrainian Trotskyists published the newspaper Robitnychi visty (1933–8). Two newspapers founded during the Second World War, Ukraïns’ke zhyttia (Winnipeg) (1941–65) and Ukraïns’ke slovo (Winnipeg) (1943–65), served pro-Soviet Ukrainian-Canadian Communists and merged in 1965 to form Zhyttia i slovo (Toronto), published in Toronto until 1991. From 1947 to 1991 the English-language Ukrainian Canadian was published by the Association of United Ukrainian Canadians. In 1991 the two publications were succeeded by the Ukrainian Canadian Herald/Ukraïns’ko-kanadas’kyi vinsyk .

The Roman Catholic hierarchy funded the first Ukrainian Catholic newspaper, Kanadiis’kyi rusyn (1911–19); as Kanadiis’kyi ukraïnets’ (1919–31), it served as the principal organ of the Ukrainian Catholic church until 1927. In Edmonton Zakhidni visty (1928–31) was purchased by the Ukrainian Catholic church in 1929. In 1932 it became Ukraïns’ki visti/Ukrainian News. In the 1990s it became an independent publication. Other major Ukrainian Catholic weeklies are the Toronto-based Nasha meta, which served eastern Canada for about a half century after it was established in 1949, and Postup (Winnipeg), begun in 1959 to serve the archeparchy of Winnipeg. The monthly Svitlo (since 1938) and Beacon (begun in 1966 as Life Beacon to promote the Ukrainian rite) are publications of the Basilian monastic order. The Redemptorist Fathers have published the monthly Holos Spasytelia (formerly Holos Izbavytelia, 1923–8) from 1933 to 1984 and the theological quarterly Lohos since 1950. The Ukrainian Catholic Brotherhood of Canada has had two major publications: Biuleten’ Bratstva ukraïntsiv-katolykiv Kanady (1933–7) and Buduchnist’ natsiï (1938–50). In 1946 Youth/Iunatstvo became the national organ of Ukrainian Catholic Youth, and in 1970 the Ukrainian Catholic Women's League began to publish the quarterly Nasha doroha.

The second Ukrainian newspaper in Canada was the Presbyterian-Independent Greek Ranok (Winnipeg) (1905–20). It merged with the Methodist Kanadyiets’ (1912–16) to become Kanadiis’kyi ranok (1920–61), subsidized for most of its existence by the United Chuch of Canada; in 1961 it became Ievanhel’s’kyi ranok, the organ of the Ukrainian Evangelical Alliance of North America, which had its headquarters in the United States. In 1940 Ukrainians still within the Presbyterian church began the newspaper Ievanhel’s’ka pravda, now a magazine published in Toronto by the Ukrainian Evangelical Alliance of North America. One of several Ukrainian Baptist publications, Khrystiians’kyi vistnyk, has appeared since 1942 as the organ of the Ukrainian Evangelical-Baptist Union of Canada. The Seventh-Day Adventists, Pentecostals, and Jehovah’s Witnesses have also published various Ukrainian-language periodicals.

The principal organ of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Canada is the semimonthly newspaper Visnyk (Winnipeg) (formerly Pravoslavnyi vistnyk, 1924–7), published by the consistory since 1928. Other Orthodox publications have included Ridna tserkva (1935–40), published by Wasyl Swystun during the religious controversy of the 1930s; Tserkva i narid (Winnipeg) (1949–51); and two theological monthlies edited by Metropolitan Ilarion (Ivan Ohiienko), Nasha kul’tura (Winnipeg) (1951–3) and Vira i kul’tura (1953– 67 and 1974–5). In addition to Ukraïns’kyi holos, the Orthodox laity has the magazine Promin’, published monthly since 1960 by the Ukrainian Women's Association of Canada. Sumkivets’, the national quarterly of the Canadian Ukrainian Youth Association since 1967, expired in the late 1970s.

The first publication of the nascent hetmanite movement was Probii (1924) followed by Kanadiis’ka Sich (1928–30), the official organ of Ukrainian monarchists in Canada. For most of its existence Ukraïns’kyi robitnyk (1934–56) supported the United Hetman Organization, but its successor, Vil’ne slovo, became a nonpartisan weekly. Since the Second World War the monarchist viewpoint has been presented by Nasha derzhava (1952–5) and Bat’kivshchyna (Toronto) (1955–).

The newspaper Novyi shliakh became the organ of the Ukrainian National Federation in 1932. Holos molodi (1947–54), MUN Beams (1955–66), and New Perspectives (est 1971) were publications of the Ukrainian National Youth Federation of Canada; Zhinochyi svit has been the monthly magazine of the Ukrainian Women's Organization of Canada since 1950.

By the Second World War the Ukrainian community had also published miscellaneous Russophile, children’s, agricultural, home, special-interest, and other newspapers and periodicals. Satire and humor were at their richest in the interwar period, in Pavlo Krat’s socialist Kadylo (1913–18), Yakiv Maidanyk’s Vuiko (1917–27) and Vuiko Shtif (1927–9), and Stepan Doroshchuk’s Tochylo (1930–47).

The largest newspaper launched by the third wave of immigration is Homin Ukraïny (1948–), which soon became the unofficial organ of the Canadian League for Ukraine's Liberation (now the League of Ukrainian Canadians). Na varti (1949–52) and Krylati (after 1963) have been the major publications of the Ukrainian Youth Association. Moloda Ukraïna (Toronto) represented the Ukrainian Democratic Youth Association from 1951. There have been three major Plast organs: Iunak and Plastovyi shliakh in the 1960s, and Hotuis’, transferred to Toronto from New York in the early 1970s.

Other émigré organizations, as well as educational, professional, and special-interest groups emerging after the Second World War, have produced many periodicals of national or local interest. They include Student, the often provocative newspaper of the Ukrainian Canadian Student's Union; Ukrainian Canadian Review, published occasionally since 1966 by the Ukrainian Canadian Professional and Business Federation; My i svit, an émigré magazine that moved to Toronto from Paris in 1955; and Novi dni, a literary magazine published from 1950. The number of English-language periodicals is increasing.

Ukrainian publishing houses have brought out a great many Ukrainian-language books, pamphlets, and annual calendar-almanacs, as well as a growing number of titles in English. Book publishers since 1945 have included Homin Ukrainy, Dobra Knyzhka, Yevshan-Zillia, Novi Dni, the Basilian Press, and Novyi Shliakh in Toronto; the Redemptorist Press in Yorkton; Ukrainian News Publishers in Edmonton; and Trident Press, the Ukrainian Greek Orthodox Church of Canada, the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences, and Ivan Tyktor Publishers in Winnipeg. The majority of these were dead or moribund by the year 2000. The sort of Ukranian-language titles they might have once published are now more commonly printed in Ukraine, albeit in much smaller numbers. The Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Shevchenko Scientific Society, and the Ukrainian Canadian Research Foundation have published scholarly monographs. Since 1978 the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press has been the most active academic publisher.

Theater. Amateur drama clubs flourished among the early Ukrainian immigrants, often in conjunction with the local Prosvita societies, reading rooms, or people's homes. Most performed traditional favorites, but they also staged plays that portrayed the immigrant Canadian experience. The more significant Ukrainian-Canadian playwrights who produced Ukrainian-language works included Myroslav Irachan and Pylyp Ostapchuk (Pylypenko). Between 1928 and 1934 there were two semiprofessional theater companies in Winnipeg, the Prosvita Rusalka Theater and the UNF Travelling Stock Theater. Local Ukrainian communities across Canada supported drama groups as well, but by the Second World War the popularity of these groups was declining.

Professional actors and experienced theater personnel among the third wave of immigrants, including Mykhailo Tahaiv, Anna Tahaiv, Lavrentii Kempe, Ivan Kurochka-Armashevsky, and S. Telizhyn, revitalized Ukrainian theater, and Toronto replaced Winnipeg as the major center. The Toronto Zahrava Theater was one of the best known Ukrainian theater companies. A new departure in the 1970s saw the small-scale introduction of Ukrainian-Canadian subject matter into English-language plays written for the general stage as well as a small number of English-language plays with Ukrainian themes (eg, Nika Rylski’s Just-a-Kommedia and Tsymbaly by Theodore Galay).

Dance. Folk dancing, maintained as a form of spontaneous expression among descendants of the early settlers, was transformed into a staged art form by Vasyl Avramenko, whose 1927 Canadian tour gave rise to folk-dance schools in larger centers and to staged, choreographed performances. Instructors of the dance groups formed during the 1930s and 1940s (the majority associated with youth organizations) were largely Avramenko’s disciples. Ukrainian professional dancers arriving in the 1950s established dance schools and ensembles in addition to performing themselves. Numerous groups emerged in the 1960s and 1970s, often with organizational ties but increasingly as independent societies. Among them were some large companies with junior and intermediate sections: the Rusalka Dance Ensemble (Winnipeg), Chaika (Hamilton, Ontario), the Ukrainian Festival Dance Company (Toronto), Kalyna (Toronto), the Shumka Dancers (Edmonton), the Ukrainian Cheremosh Society (Edmonton), the Poltava Dance Ensemble (Regina), and the Yevshan Ukrainian Folk Ballet Ensemble and Pavlychenko Folklorique Ensemble (Saskatoon). Individuals active in instruction and direction since the Second World War include Peter Marunczak, Jaroslav Klun, Peter Hladun, Chester Kuc, Tom Luchenko, and Nadia and Lucia Pavlychenko.

The spontaneous improvisations of the early immigrants were succeeded by dance repertoires shaped by Vasyl Avramenko around a few set pieces. In the 1960s some dance groups began to adopt the colorful, large-scale, and conformist style of touring troupes from Soviet Ukraine. At the same time, more attention started to be paid to formal dance training in addition to more varied repertoires and innovative choreography. In 1975 Soviet influence on Ukrainian dance in Canada became more direct with the introduction of dance seminars taught by Soviet Ukrainian choreographers. Ukrainian dance grew during the 1960s and 1970s with national media exposure and government grants to subsidize tours by the larger companies, dance workshops, and seminars. In the 1970s approximately 100 amateur troupes represented various age groups and skill levels. By the 1980s the number of Ukrainian dance troupes in Canada had increased to over 200. In the post-independence period, senior Ukrainian dance ensembles in Canada commonly began to employ dancers from Ukraine as instructors. In addition to major, almost professional productions by large metropolitan companies, there are a number of annual regional festivals where Ukrainian dancers perform regularly: Canada’s National Ukrainian Festival in Dauphin, Manitoba; the Pysanka Festival in Vegreville, Alberta; the Vesna Festival in Saskatoon; and Toronto’s Bloor West Village Ukrainian Festival.

Music. The folk tradition is a rich source for Ukrainian music in Canada. Choral singing, introduced by the first immigrants, became a national art form with the creation of large, trained choirs after the 1922 Canadian tour of the Ukrainian National Choir from Europe under Oleksander Koshyts. Among the leading interwar choirs were the Boian Chorus of the Ukrainian National Home Association, the Banduryst Chorus of the Saints Volodymyr and Olga Cathedral, and the Prosvita Choir in Winnipeg; the choir of the Ukrainian National Home in Toronto; and the Ukrainian National Federation and Saint Sophia choirs in Montreal. In the 1930s Koshyts taught music history and theory and choral directing in Winnipeg. Conductors of the period included Bohdan Kovalsky, Yakiv Kozaruk, Yevhen Turula, Volodymyr Bohonos, and Pavlo Matsenko. With the third immigration came such professionals as Ivan Kovaliv, conductor of the Saint Nicholas Church choir and founder of the Lysenko Musical Institute in Toronto, Nestor Horodovenko of the Ukraina choir in Montreal, and Lev Turkevych of the Prometei choir in Toronto. Since the Second World War noted amateur conductors have included Walter Klymkiw and Vasyl Kardash. The third immigration stimulated instrumental, solo, and chamber music, particularly in the larger cities where Ukrainian symphony concerts were held. A number of more ambitious undertakings were attempted by the Canadian Ukrainian Opera Chorus under the direction of Volodymyr Kolesnyk, a former Soviet Ukrainian conductor who defected to Canada in 1972. With the major exception of classical Ukrainian musicologist Pavlo Matsenko, the musical community has lacked qualified critics.

The 1930s and 1940s witnessed the appearance of professional musicians of Ukrainian descent raised in Canada, including Winnipeg’s Donna Grescoe (violinist). Of these Ukrainian musicians who immigrated to Canada, the opera singer Mykhailo Holynsky is probably best known. The more accomplished professional instrumentalists, singers, and composers include George Fiala (composer), Luba Zuk and Ireneus Zuk (pianists), Zenoby Lawryshyn and Roman Hurko (composers), Steven Staryk (violinist), and Anna Chornodolska and Roxalana Roslak (classical vocalists). In 1974 Ukrainians sponsored performances by the Edmonton and Winnipeg symphony orchestras that featured Ukrainian composers and artists. Ukrainians in Toronto (1979) and Edmonton (1981) also staged the opera Kupalo under Volodymyr Kolesnyk, former director of the Kyiv Theater of Opera and Ballet.

Beginning in the 1940s and 1950s a distinct Ukrainian-Canadian popular music began to evolve. Drawing on folk tradition and Canadian elements, it has acquired mass appeal through the long-playing record (notably on the V-Records label), radio, and television. In western Canada Ukrainian country music has been represented by such artists as Mickey and Bunny (Sklepowich); other popular singers have included Anthony Stecheson (Tony the Troubador), Walter Koster, Joan Karasevich, and Ed Evanko. In the 1960s and 1970s popular bands like the D-Drifters Five of Winnipeg and Rushnychok of Montreal provided another dimension to the new Ukrainian-Canadian music scene with a more pop-based urban sound. Some groups, notably Dumka of Edmonton incorporated elements from the style of contemporary Ukrainian vocal-instrumental ensembles (aka VIA). Since the late 1980s there has been considerably more direct contact with popular musicians and groups in Ukraine, many of whom have come to North America with concert tours or to appear at Ukrainian festivals. Some innovative popular Ukrainian music has been produced in recent times by people like Taras Shipowick and Alexia Kochan.

The tsymbaly, bandura, and mandolin have been played in Canada since the early 1900s, although the popularity of mandolin and bandura choruses has fluctuated and tsymbaly have been most common on the Prairie provinces.

Architecture, painting, graphic arts, and sculpture. Church architecture has evolved greatly since the erection of modest prairie pioneer structures by anonymous folk builders. The first architect to have widespread impact was the Oblate priest Philip Ruh. Examples of his monumental elaborate style are Saint Josaphat’s Catholic Cathedral in Edmonton and the Ukrainian Catholic church in Cook’s Creek, Manitoba. Since the 1960s architect Radoslav Zuk has skillfully integrated traditional Ukrainian and contemporary elements to design modern churches, such as the Holy Eucharist Church in Toronto, the Holy Family Church in Winnipeg, and Saint Stephen’s in Calgary, all of them Ukrainian Catholic. Other architects of Ukrainian churches include Yurii Kodak and Victor Deneka.

Such Ukrainian folk arts as easter egg ornamentation and embroidery remain productive forms of individual artistic expression. In danger of being lost in the early 1940s, they have been revived by Ukrainian Canadians of all generations. Wood carving has been largely confined to iconostasis, ciborium, and altar construction.

Several Canadian artists of Ukrainian descent have drawn on their ethnicity in the Canadian context; others (particularly immigrants) have relied more heavily on the Ukrainian artistic tradition in subject matter, style, or form. In the 1920s cartoonist Yakiv Maidanyk satirized the Ukrainian immigrant community and interpreted Canadian society to his readers. William Kurelek, whose pioneer prairie experience inspired many of his paintings, was widely recognized by the Canadian artistic community. Leo Mol (Leonid Molodozhanyn), the international-award-winning sculptor, has done several Ukrainian and Canadian pieces, but his work is wide-ranging. Emigré artists of the 1950s who continued to produce in Canada include Myron Levytsky (painting, graphic art), Ivan Keivan (graphic art, art criticism), and Roman Koval (sculpture, portraits, landscapes); other members of the group include Lida Palii (graphic art) and Mykola Bidniak, Halyna Novakivska, Andrii Babytsch, Ivan Bielsky, Myroslav Styranka, Omelian Telizhyn, and Petro Magdenko (painting). Notable church painters have been Yuliian Butsmaniuk and Wadym Dobrolige. In 1955 émigré artists established the Ukrainian Association of Creative Artists in Canada in Toronto. Artists of Ukrainian background active in the Canadian artistic community have included Michael Kuczer, Lillian Klimec, Robert Kost, Peter Shostak, Ronald Kostyniuk, Peter Kolisnyk, Karen Kulyk, I. Hrytzak, Laryssa Luhovy, Kenneth Mamchure, Ihor Kordiuk, Irma Osadtsa, Vira Yurchuk, Christine Kudryk, Ksenia Aronetz, Primrose Diakiw, F. Tymoshenko, and Lillian Sarafinchan (painting); Natalka Husar and Don Proch (mixed media); Ruslan Logush (silkscreen prints); Adriane Lysak (engraving, woodcuts); and Ed Drahanchuk (ceramics).

The first Ukrainian art gallery, My i Svit, was established in Toronto in 1958 by Mykola Koliankivsky, who later moved his collection to Niagara Falls, Ontario. Also exhibiting the work of Ukrainian-Canadian artists have been the Ukrainian Cultural and Educational Centre in Winnipeg and the Ukrainian Canadian Art Foundation in Toronto.

Electronic arts (film, radio, television). Ukrainian filmmaking was poorly developed until Bohdan Soluk, Lev Orlyhora (pseud. of Lev Sylenko), and Walter Wasik in the Toronto area became involved after the Second World War. Their productions, which have largely romanticized the Ukrainian past or have been anti-Soviet statements, have included Chornomortsi (Black Sea People, 1952), Hutsulka Ksenia (Ksenia, the Hutsul Girl, 1956), Lvivs’ki katakomby (Lviv Catacombs, 1954), Pisnia Mazepy (Song of Mazepa, 1960), and the Wasik Films productions, Zhorstoki svitanky (Cruel Dawn, 1965), Nikoly ne zabudu (I Shall Never Forget, 1969), Marichka (1974), and Zashumila verkhovyna (Whispering Highlands, 1975). The National Film Board of Canada (NFB) has produced a number of films and shorts about Ukrainian Canadians, ranging from the early documentary-like Ukrainian Winter Holidays (1943) and Ukrainian Dance (1944) to Kurelek: The Ukrainian Pioneers (1974), Roman Kroitor’s Strangers at the Door (1977), H. Spak’s Wood Mountain Poems (1979, featuring poet Andrew Suknaski) and Halya Kuchmij’s Strongest Man in the World (1980) and Laughter in My Soul (1983), and John Paskievich’s Ted Baryluk’s Grocery (1982) and My Mother’s Village (2001). Reflections of the Past (1974), an impressionistic view of the pioneer experience in Manitoba by Slavko Nowytski, was commissioned by the Ukrainian Cultural and Educational Centre in Winnipeg. While films about Ukrainians in Canada have tended to be ‘success’ oriented or to focus on folkloric and ethnographic elements, some have taken a more critical approach: the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation's (CBC) Another Smith for Paradise (1973); the NFB’s Teach Me to Dance (1978, with script by Myrna Kostash); and ‘1927’ (1978), a CBC television drama written by George Ryga.