Graphic art

Graphic art [графіка; hrafika]. A form of pictorial art that is predominantly linear in effect and includes original drawings and illuminations as well as reproductions, such as book illustrations, bookplates, posters, and prints, that are made by various printing techniques (woodcut, engraving, etching, aquatint, lithography, and the like).

In Ukraine, from the 11th to the 16th century manuscript books were ornamented with headpieces, initials, tailpieces, and illuminations. Many of these features appeared as well in the first printed books. Lviv became the first center of printing and graphic art after Ivan Fedorovych (Fedorov) established his printing house there in 1573, which later became the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood Press. One of the first influential engravers was Lavrentii Fylypovych-Pukhalsky. Graphic-art centers also arose at printing presses established in Ostroh, Volhynia (where the Ostroh Bible was published in 1581), in Striatyn (see Striatyn Press) and Krylos in Galicia, and finally in Kyiv at the highly advanced engraving shop of the Kyivan Cave Monastery Press. In the first half of the 17th century Tymofii Petrovych of Kyiv, who illustrated the Discourses of Saint John the Evangelist (1623), and Anastasii Klyryk of Lviv were renowned engravers; other craftsmen are only known by their first name—eg, Master Luka, Master Illia, or Master Prokopii—or by the initials they left on their engravings.

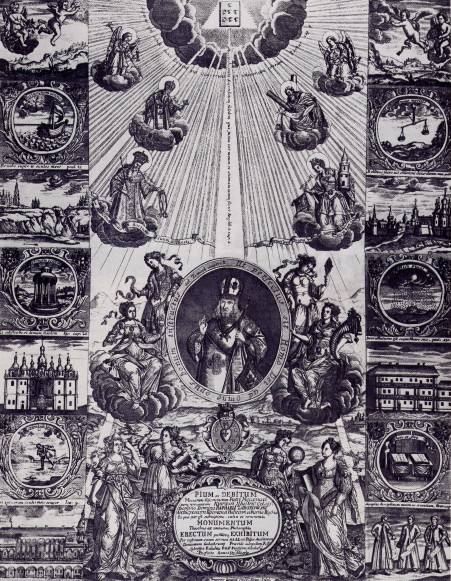

Beginning in the second half of the 17th century, in addition to religious themes, secular and everyday subjects, portraits, town plans, etc were depicted in graphic form. Realism, which came to Ukraine with the Renaissance and baroque art, fundamentally changed graphic art. During the Ukrainian baroque period, which coincided with the Hetman state, engraving became highly developed, utilizing not only new forms, but also allegory, symbolism, heraldry, and very ornate decoration. These characteristics suited the belligerency and dynamism of the Cossack period, whose apogee during the hetmancy of Ivan Mazepa defined the artistic fashion for the late 17th and early 18th centuries. At this time, graphic art began to be used for purposes other than book publishing. An interesting new form, the so-called tezy (theses)—large graphics on paper or silk, dedicated to famous political or church figures with their portraits and elaborate poetical dedications—became popular.

The turn of the 18th century saw the emergence of the first engraved landscapes—eg, Dionisii Sinkevych's view of the Krekhiv Monastery (View of Krekhiv Monastery, 1699)—as well as the first engravings with historical themes—eg, Nykodym Zubrytsky's depiction of the siege of Pochaiv (Turkish Siege of Pochaiv_(1704).jpg">Turkish Siege of Pochaiv, 1704). Zubrytsky produced 67 engravings for Ifika iieropolitika (1712). He, Sinkevych, and other baroque engravers (eg, Yevstakhii Zavadovsky) came from Western Ukraine. But the main center remained Kyiv: engraving was taught at the Kyivan Mohyla Academy and the Kyivan Cave Monastery Press, whose students were often sent to study abroad, especially in Germany. The most famous Kyivan craftsman of the time was the portraitist and illustrator Oleksander Tarasevych (active from 1667 to 1720). His pupil Danylo Haliakhovsky produced the great teza with the portrait of Ivan Mazepa. Other notable craftsmen were Ivan Shchyrsky, Zakhariia Samoilovych, Leontii Tarasevych, Ivan Strelbytsky, and Ivan Myhura, who was known for his very personal style incorporating folk art motifs. All these craftsmen were in great demand in Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Moldavia, and Muscovy.

After the defeat of Ivan Mazepa at the Battle of Poltava in 1709, cultural life in Ukraine declined because of Russian political restrictions and the migration of Ukrainian intellectuals and artists to Saint Petersburg. Nevertheless, Kyiv still had such craftsmen as Averkii Kozachkivsky and especially Hryhorii K. Levytsky, the most prominent Ukrainian engraver of the 18th century who created the large teza of Archbishop Rafail Zaborovsky (Teza of Archbishop Rafail Zaborovsky, 1739). In Western Ukraine, particularly in Pochaiv, Volhynia, renowned engravers included Adam Hochemsky, Yosyf Hochemsky, Ivan Fylypovych, and Teodor Strelbytsky.

The technique of lithography, which was developed in Europe in the 1790s, was taken up by Ukrainian artists in Lviv in 1822, in Kyiv from 1828, and later in Odesa and other centers. Etching as a technique was made popular by Taras Shevchenko, who in 1844 published an album of six etchings, Zhivopisnaia Ukraina (Picturesque Ukraine), and later executed numerous portraits, landscapes, and illustrations. Shevchenko was also a pioneer in modern aquatint.

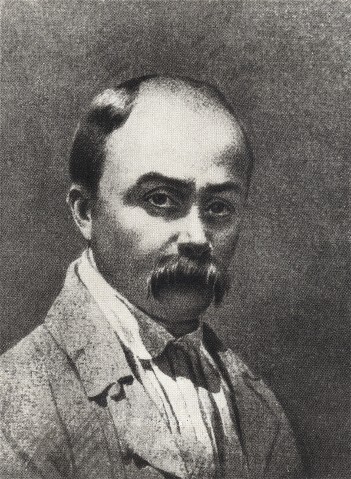

The 1863 and 1876 Russian prohibitions against Ukrainian-language publications (see Valuev circular and Ems Ukase) delayed the further development of graphic arts in Ukraine. Conditions improved somewhat at the beginning of the 20th century, and new graphic artists and illustrators appeared, such as Ivan Izhakevych, Serhii Vasylkivsky, Mykola Samokysh, Opanas Slastion, Amvrosii Zhdakha, and in Lviv, Olena Kulchytska. All of them were largely influenced by realism. Vasyl H. Krychevsky first explored the possibilities of a new style, combining elements of traditional Ukrainian printing with popular folk motives and using the latest graphic technology, particularly in book publishing.

The major craftsman of modern Ukrainian graphic art was Heorhii Narbut, who became renowned in Saint Petersburg in the Russian circle Mir Iskusstva and its journal Apollon. After the Revolution of 1917, he returned to Kyiv, where he made his most significant contributions to the development of Ukrainian graphic art. His designs of official Ukrainian National Republic bank notes, postage stamps, seals, and book and journal covers and decorations are among the finest achievements of Ukrainian graphic art. In these and other works, Narbut aimed at a synthesis of Ukrainian baroque graphic traditions with a modern approach and flowing, rhythmic linearity. At the newly established Ukrainian State Academy of Arts in Kyiv, he taught his craft to such artists as Oleksander Lozovsky, Marko Kyrnarsky, Kostiantyn Piskorsky, and Robert Lisovsky.

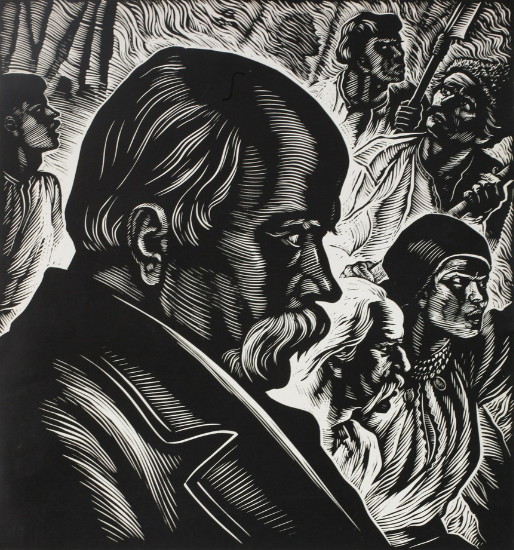

Graphic art was also nurtured by Mykhailo Boichuk, who advocated the continuation of Ukrainian artistic traditions, particularly Byzantine ones, through modern art forms; his followers include his wife Sofiia Nalepinska, Ivan Padalka, Olena Sakhnovska, M. Kotliarevska, Vasyl Sedliar, and Oleksander Dovhal. The realist style was espoused by the talented and prolific Vasyl Kasiian, who produced many engravings and illustrations on political and labor themes; as a professor at the Kharkiv Art Institute and the Kyiv Art School, he had a major influence on the development of socialist realism in graphic art. Other artists such as Antin Sereda, Adolf Strakhov, Leonid Khyzhynsky, Havrylo Pustoviit, and Borys Kriukov also contributed to the development of Soviet Ukrainian graphic art in the 1920s and 1930s.

In interwar Polish-ruled Galicia, there arose in Lviv an important group of graphic artists who were closely connected with artists in other European cities. The more prominent of these were Pavlo Kovzhun, who was well known for his cubist and constructivist book designs, Mykola Butovych, Robert Lisovsky, Petro P. Kholodny, Nil Khasevych, Viktor Tsymbal, Vasyl Masiutyn, Halyna Mazepa, and Edvard Kozak. The Lviv exhibit of Ukrainian graphic art in 1932 was one of the biggest events of its kind, with 1,392 works from all branches of the graphic arts, including works by artists from Soviet Ukraine. Ukrainian graphic artists also exhibited in various Western European cities; eg, in Berlin at the State Art Library in 1933 and in Rome in 1938.

After the Second World War all graphic art in Ukraine had to conform to the official style of socialist realism and was used as an instrument in political and economic propaganda. It was only during the brief thaw after Joseph Stalin's death that Western influences were allowed. In the 1980s a number of new talented artists attempted to expand the boundaries of socialist realism while remaining faithful to the tradition of the Vasyl Kasiian school. The more prominent postwar artists of the prerevolutionary generation are Mykhailo Derehus, Oleksandr S. Pashchenko, and Valentyn Lytvynenko. Artists born after the Revolution of 1917 included Serhii Adamovych, Anatolii Bazylevych, O. Danchenko, H. Havrylenko, Oleksander Hubariev, Sofiia Karaffa-Korbut, Volodymyr Kutkin, Ivan Ostafiichuk, V. Panfilov, Vasyl Perevalsky, I. Pryntsevsky, Bohdan Soroka, and Heorhii Yakutovych.

After the Second World War many Ukrainian artists emigrated to the West, especially to North and South America, where they continued to make important contributions: eg, Jacques Hnizdovsky, who settled in the United States and achieved international prominence with his woodcuts, Petro Andrusiv, Volodymyr Balias, Mykola Butovych, Mykhailo Dmytrenko, Ivan Keivan, Edvard Kozak, Petro P. Kholodny, Myron Levytsky, Halyna Mazepa, and Viktor Tsymbal. A postwar generation of Western graphic artists of Ukrainian origin, including Bohdan Bozhemsky, Liuboslav Hutsaliuk, Adriane Lysak, Ruslan Logush, Andrij Maday, Arcadia Olenska-Petryshyn, Zenowij Onyshkewych, and Borys Pachovsky, also arose; it was joined by such Soviet émigrés as Rem Bahautdyn, Vitalii Lytvyn, Volodymyr Makarenko, and Volodymyr Strelnikov.

(See also Art, Illumination, Illustration, and Printing.)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Makarenko, M. Ornamentatsiia ukraïns’koï knyzhky XVI–XVII vv. (Kyiv 1926)

Popov, P. Materiialy do slovnyka ukraïns’kykh graveriv (Kyiv 1926; addendum 1927)

Ksylohrafichni doshky Lavrs’koho muzeiu (Kyiv 1927)

Kataloh hrafichnoï vystavky ANUM (Lviv 1932)

Antonowytsch, D. Katalog der Ausstellung ukrainischer Graphik (Berlin 1933)

Sichyns’kyi, V. Istoriia ukraïns’koho graverstva XVI–XVII st. (Lviv 1937)

Hrafika v bunkrakh UPA (Philadelphia 1952)

Kataloh vystavky mysttsiv suchasnoï ukraïns’koï knyzhnoï hrafiky (Toronto 1956)

Vrona, I. Ukraïns’ka radians’ka hrafika (Kyiv 1958)

Zapasko, Ia. Ornamental’ne oformlennia ukraïns’koï rukopysnoï knyhy (Kyiv 1960)

Kasiian, V.; Turchenko, Iu. Ukraïns’ka dozhovtneva realistychna hrafika (Kyiv 1961)

Turchenko, Iu. Ukraïns’kyi estamp (Kyiv 1964)

Stepovyk, D. Vydatni pam'iatky ukraïns’koho hraverstva XVII stolittia (Kyiv 1970)

Ketsalo, Z. (comp). Hrafika L’vova (Kyiv 1971)

Ovdiienko, O. Knyzhkove mystetstvo na Ukraïni, 1917–1974 (Kyiv 1974)

Lohvyn, H. Z hlybyn: Davnia knyzhkova miniatiura XI–XVIII stolit’ (Kyiv 1974)

Stepovyk, D. Oleksandr Tarasevych: Stanovlennia ukraïns’koï shkoly hraviury na metali (Kyiv 1975)

Fomenko, V. Hryhorii Levyts’kyi i ukraïns’ka hraviura (Kyiv 1976)

Stepovyk, D. Ukraïns’ka hrafika XVI–XVIII stolit’: Evoliutsiia obraznoï systemy (Kyiv 1982)

Stepovyk, Dmytro. Ukraïns’ka hraviura baroko (Kyiv 2012)

Sviatoslav Hordynsky

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 2 (1988).]

%20title%20page.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20(1708)%20(detail).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)