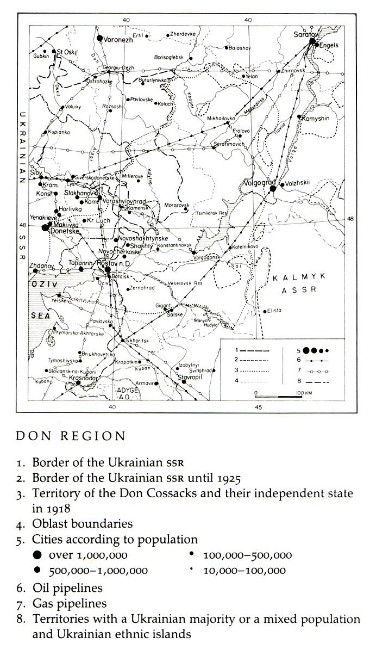

Don region

Don region (Донщина; Donshchyna). A historical-geographical region, the former territory of the Don Cossacks—the oblast (domain) of the Don Host. It is located in the basin of the lower and middle Don River. In 1914 the territory constituted the Oblast of the Don Cossack Host with an area of 164,600 sq km and a population of 3.9 million. Its southwestern part falls within Ukrainian ethnic territory. The non-Ukrainian part of the Don region borders on Ukrainian ethnic territory for 1,100 km, from Novokhopersk (Voronezh oblast) in the north to Oziv in the south. Today a small western part of the Don region belongs to Ukraine and is divided between Donetsk oblast and Luhansk oblast. The rest of the region belongs to the Russian Federation and is within Rostov oblast and Volgograd oblast.

The region consists of lowland plains with a weakly developed relief and somewhat more elevated and divided ridges. Most of the region is part of the Lower Don Lowland, which is separated from the Middle Donets Lowland in the north by the East Donets Ridge. The most elevated and divided area of the Don region is in the southwest and forms part of the Donets Ridge. The climate is continental: the temperature in July is 22 to 24 C, and in January -5 to -9 C. The annual precipitation is 250–350 mm. The whole region is covered by steppe—narrow-leaved, fescue-feather-grass steppes in the west and dry-grass steppes in the east. This is an agricultural region, producing mainly wheat, corn, and barley. It has a low population density (15-40 people per sq km), except in the southwest (the eastern Donbas). Because of coal deposits and the accessibility of the Sea of Azov, heavy industry has developed here. The largest cities of the Don region—Rostov-na-Donu, Novocherkassk (former capital of the Don Cossacks), Shakhty, Novoshakhtinsk, Kamensk-Shakhtinskii, Tahanrih, and Oziv—are located in the southwest.

Nationalities. The nationalities question here is quite complex, owing to centuries of colonization. Most of the original population consisted of Don Cossacks, who settled all of the northern and middle part of the Don River and a narrow corridor in the lower Don that today separates the main Ukrainian ethnic territory from the formerly Ukrainian-populated Kuban region and areas of eastern Subcaucasia. From this corridor extends another one, westward along the Donets River and beyond Luhansk, running through the territory of Ukraine. It should be pointed out that pure Russian is used only in the upper Don, in the basins of the Khoper and Medveditsa rivers. The Don Cossacks, who lived along the middle Don up to the Tsimla River, particularly in the northwest, speak a language that is influenced by Ukrainian. The language and ethnography of the inhabitants of the Lower Don also bear strong traces of Ukrainian. Ukrainian linguistic influence is even greater in the Donets dialect and in the mixed dialects on the borders of Subcaucasia.

The western part of the Don region was colonized independently of the Don Cossacks by the Zaporozhian Cossacks and Ukrainian peasants. Ukrainian migration into this territory was particularly vigorous after the abolition of serfdom; it then spread south into the sparsely settled regions adjacent to the Kuban and the eastern Subcaucasian steppes. Russian peasants settled here in smaller numbers. The cities, especially Rostov-na-Donu, and the Donets Basin attracted workers, mostly Russians. Besides Ukrainians and Russians, the Don region was settled also by Germans, Armenians, Jews, and Greeks, who gravitated towards the cities. The steppes in the southeast were inhabited by the Kalmyks. The non-Cossack population of the Don region was called inohorodni (Russian: inogorodnye [those from other towns]). Colonization increased the proportion of the inohorodni: they constituted 44 percent of the population in 1886, 50.5 percent in 1895, and 60 percent in 1910 (ie, a majority of the population).

On the basis of official statistics published in 1897, Ukrainians constituted a majority (61.7 percent) in Tahanrih county and a large minority in Donets county (38.9 percent), Rostov county (33.6 percent), Salsk county (29.3 percent), and Novocherkassk county (18.9 percent). The Ukrainian ethnic territory in the Don region consisted of three parts: (1) the northern part between the Donets River and the Don River in the basin of the Kalitva River, containing the towns of Millerove, Chortkove, and Morozivske and separated by a non-Ukrainian strip of settlement along the Donets; (2) the southwestern part of the Tahanrih area; and (3) the lands north of the Manych and Sal rivers and adjacent to Subcaucasia. After the Bolsheviks occupied the Don region, the Tahanrih area and parts of Donets and Cherkassk counties were annexed to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. In 1925 most of these territories were again separated from Ukraine; hence, only small border areas of the Don region remain in Ukraine today. The part of the region that was settled by Ukrainians but belongs to the Russian Federation has an area of 23,800 sq km and had a population in 1926 of 778,000, 76.8 percent of which was Ukrainian (81.9 percent of the rural population and 33.9 percent of the urban population). This population had a low level of national consciousness and easily became Russified, particularly in the towns and industrial areas, after its separation from the Ukrainian SSR.

The national composition of the Don region has changed considerably since the 1920s and early 1930s. The proportion of Ukrainians has declined rapidly because Ukrainians have lack national rights within the Russian SFSR and then in the Russian Federation and they have become linguistically and nationally Russified. The cities attract large numbers of Russians from the Russian heartland, and Cossack consciousness is waning. The present national composition of the Don region is unknown, because the Soviet and Russian censuses have dealt only with whole oblasts and have been inaccurate. The national and linguistic statistics have been manipulated to prove that the Ukrainian-Russian border coincides with the ethnic boundary.

History. At the beginning of the historical period the Don region belonged to the Khazar Khaganate. In the 10th–11th century the Slavs, who had penetrated previously to the lower Don River, began to settle the southern part of the region. In 965 Prince Sviatoslav I Ihorovych conquered the southwestern part of the Khazar state and captured the fortress and city of Sarkel on the Don. A principality administered from Tmutorokan at the mouth of the Kuban River was set up. Bila Vezha on the Don was its main manufacturing and trading center, and Rusiia at the mouth of the Don was its main port. At the same time the Rus’ princes’ struggle with the nomadic Turkic tribes that continually moved in from the east began. In the 12th century the Cumans cut off the Tmutorokan principality from the Kyivan Rus’ state, and most of the principality’s Slavic population returned to Rus’. Yet a significant portion of the population remained on the lands beyond the Don and on the Sea of Azov coast. Under conditions of constant warfare with the Turkic invaders, this population organized itself into seminomadic, armed bands, known in the 12th–13th century as the brodnyky (wanderers). Most historians consider the brodnyky to be the precursors of the Cossacks, who appeared in the 15th century in southern Ukraine, in the Don region, and on the southeastern frontiers of Muscovy. The early Cossacks were light cavalrymen who offered their services to neighboring rulers. The Don Cossacks served the Moscow princes and then the tsars and constituted Muscovy’s southern line of defense against the Turks, Crimean Tatars, Circassians, and others. The Don Cossacks came from the indigenous population of the region and from the free settlers from Muscovy and Ukraine who belonged to various estates and were seeking new homes, mostly for social reasons.

Like the Zaporozhian Cossacks, the Don Cossacks (also called dontsi) organized their own military-social order of a republican type. It was known as the Great Don Host (Vsevelyke Viisko Donske). The supreme authority rested with the Great Military Circle (Velykyi Viiskovyi Kruh), which decided the most important questions, such as war, peace, alliance, and election of the otaman and officers. At first the Muscovite tsars recognized the separate order and privileges of the Don Cossacks, and in return the Cossacks fought on the side of the tsars in a number of wars. But throughout the 17th century Muscovy tried to restrict Cossack autonomy in various ways. In 1671 the Great Don Host lost its independence and swore allegiance to the Russian tsar. In the 17th–18th century the Don Cossacks often rebelled to defend their privileges (S. Razin, Kondratii Bulavin, E. Pugachov).

The Russian tsars continued to curtail the autonomy of the Don Cossacks in the 18th century. After Kondratii Bulavin’s unsuccessful rebellion in 1707–8, which was motivated by social and national oppression, Peter I abolished the elections of the otaman. The Cossacks had lost the right to conduct their own foreign relations even before then. In 1721 the Host became subject to the Russian Military Collegium. The Military Circle slowly lost its influence and was summoned only for ceremonial functions: the issuing of the tsar’s edicts, the distribution of rewards, etc. Real power rested with the Military Chancellery, which decided on all matters. The reform of 1775 set up a military-civil administration patterned on the gubernial administration. At the end of the 18th century serfdom was introduced in the Don region. The Cossack officers became part of the Russian gentry, and the peasants became their serfs. The free Cossacks were formed into a military estate, which constituted an important part of the Russian army, mainly its cavalry. In the mid-19th century the Don Cossacks provided 80 cavalry regiments, each Cossack supplying his own arms and horse.

The Russian authorities were alert to the slightest signs of Don separatism. In 1773 the Don otaman S. Efremov, a member of the Efremov otaman ‘dynasty,’ was accused of separatist tendencies and anti-Russian ties with the gortsy (Caucasian mountain peoples), Tatars, and Zaporozhian Cossacks. He was arrested and taken to Saint Petersburg. He was later rehabilitated; but the Russian authorities continued to fear an autonomist movement in the region and punished its supporters very severely. In 1792 a Cossack rebellion led by F. Sukhorukov and I. Rubtsov broke out and was suppressed by the government. In 1800 the brothers E. and P. Gruzinov (Georgians by origin), who were decorated officers of the Russian Guard but also Don patriots, were publicly tortured to death in Cherkassk on Paul I’s orders. Their associates were put to death for ‘treason against the fatherland’ and their plans to liberate the Don region from Russia.

After the Revolution of 1917 the autonomist movement became widespread in the Don region. The traditional Cossack order was revived, and a regional (krai) government headed by General A. Kaledin was set up; it did not recognize the Soviet government and proclaimed itself the supreme power. From 1917 to 1920 a war between Soviet Russia and the anti-Bolshevik forces took place in the region. In May 1918, after the region was cleared of the Bolsheviks, the constitution of the Great Don Host was adopted. The Don Cossack army became the main anti-Bolshevik force. In opposition to the independence movement among the Cossack rank and file, the officers (the otamans P. Krasnov and A. Bogaevsky, the head of the Great Military Circle V. Kharlamov, etc) worked towards reinstating a unified Russian state. They tried to win the Kuban population over. Anton Denikin’s Volunteer Army got its main support against the Bolsheviks from the Don Cossacks and the Don regional government.

Even after the defeat of the White forces, the region continued to give rise to anti-Soviet unrest and rebellions. The Soviet government abolished Don autonomy, stripped many Cossacks of their civil rights, and restricted their numbers in the military (until 1937). Like the population of Ukraine, the region’s population strongly resisted collectivization; it, too, sustained great losses during the famine of 1932–3. Several Soviet cavalry formations that were called Cossack fought in the Second World War. The Germans organized separate units of Don Cossacks from prisoners of war and used them to fight the Soviet Army. After Germany’s surrender the Allies handed over 2,750 officers and about 15,000 captured Don Cossacks to the Soviets.

The Soviet government was destroying the sociocultural distinctiveness and autonomy of the Cossack population, in accordance with the resolution of the All-Russian Worker-Cossack Congress that was held in Moscow in 1920: ‘The Cossacks are not at all a separate people or nation, but constitute an inseparable part of the Russian people.’

There is a Cossack independence movement abroad, supported mainly by Don Cossack émigrés.

Relations between the Don region and Ukraine. The Cossack democracies of the Don region and Ukraine, because of their proximity, similar structure, and frequently common interests, maintained close relations from their inception until the 18th century. The Don Cossacks and Zaporozhian Cossacks exchanged correspondence and envoys, provided mutual military support, and fought campaigns together. Don inhabitants often resettled in the Zaporizhia, and even more Zaporozhians migrated to the Don. As separate states, the Don domain and the Zaporizhia conducted their own diplomatic relations with neighboring countries. Muscovy took a keen interest in the affairs of the two Cossack states, particularly in the relations between them. Many documents prove that these relations were good. In 1632 Muscovy received a report that the Don Cossacks and Zaporozhian Cossacks had signed a mutual defense treaty. In 1649 and 1650 Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky sent letters to the Don Host. In 1668 Hetman Ivan Briukhovetsky wrote the Don Cossacks: ‘Do not be tempted by the deceitful rewards of Muscovy. I warn you: as soon as it suppresses us, it will start planning the conquest of the Don region and the Zaporizhia.’ The Zaporozhian otaman Ivan Sirko wrote similar letters. In a letter to the tsar in 1685 the Don Cossacks declared their longstanding alliance and friendship with the Zaporozhian Cossacks. One of the letters sent from the Don Host to the Zaporizhia in 1707 states: ‘The Don Cossacks and Zaporozhian Cossacks consulted with each other and pledged their souls to stand united and to care for one another as friends.’

The close ties between the Don Cossacks and the Ukrainian Cossacks were reflected in many military campaigns. Each spring a force of 1,000–2,000 Zaporozhian Cossacks arrived at the Don River and set out with the Don Cossacks on a sea campaign against the Crimea or Turkey. The Don Host and the Zaporozhian Host both played an important role in the campaigns against Muscovy at the beginning of the 17th century and in the struggle for the tsar’s throne: the Second False Dimitrii was supported by 15,000 Don Cossacks and 30,000 Zaporozhian Cossacks. Mikhail Romanov was elected tsar in 1613 mainly through the influence of the Cossacks. In 1637 the Don Cossacks and Zaporozhian Cossacks transferred their military camps to the Oziv region.

The Hetman state was compelled to help in suppressing Kondratii Bulavin’s rebellion, which the Zaporozhian Cossacks supported. But both Ivan Mazepa and Pylyp Orlyk counted on support from the Don Cossacks in planning an East European coalition against Moscow. From the beginning of the 18th century, after its defeat of Bulavin and Mazepa, Moscow adopted more decisive policies against the Cossacks. It tried to arouse inner strife by increasing the privileges of the Cossack starshyna and by aggravating any conflicts of interest between the Don Cossacks and Zaporozhian Cossacks. The struggle for the Bakhmut salt mines ended with Peter I’s sending his army and the Cossack regiments from Slobidiska Ukraine against the Don Cossacks and destroying almost half their settlements. Thereafter, the Donets Basin with its saltworks was granted to the Slobidska Ukrainian Izium regiment and the lands up to the Aidar River were granted to the Ostrohozke regiment. In the mid-18th century the Don Cossacks and Zaporozhian Cossacks fought over the Sea of Azov coast and fishing grounds. During Ivan Gonta’s and Maksym Zalizniak’s Koliivshchyna rebellion, Catherine II sent Don regiments into Right-Bank Ukraine to crush the Haidamaka rebels, and in 1775 she used Don regiments to destroy the Zaporozhian Sich. Thus, Moscow succeeded in dividing the Don Cossacks and Ukrainian Cossacks and even turning them against each other in order to destroy them and to expand the Russian Empire. At the beginning of the 20th century the tsarist regime used Don Cossacks to suppress peasant uprisings or revolutionary outbursts in the towns of Ukraine in order to create enmity between the Ukrainian and Don peoples.

A new relationship between Ukraine and the Don region developed after the Revolution of 1917, when both countries set up their own independent states. Relations were generally friendly. In December 1917 the government of the Ukrainian Central Rada permitted Cossack units to return home from the front through Ukraine to strengthen A. Kaledin’s anti-Bolshevik forces. The Rada’s sympathetic attitude to the Don liberation movement provoked an ultimatum from the Soviet Russian government and led to the Ukrainian-Soviet War, 1917–21. Normal diplomatic relations between Ukraine and the Don were established in 1918, after both countries were cleared of Bolshevik troops. In May 1918 a special envoy from Ataman P. Krasnov asked Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky to recognize the Don’s independence and to establish treaties with it. On 8 August 1918 the Ukrainian-Don Agreement was signed, providing mutual recognition and defining the border between the two countries. The border followed the former administrative boundaries between the Katerynoslav gubernia, Kharkiv gubernia, and Voronezh gubernia on one side and the Oblast of the Don Cossack Host on the other. Hence, the western part of the Don region and part of the Donets Basin, which were inhabited mostly by Ukrainians, remained part of the Don state. The claims of the Don government to Starobilsk county and the city of Luhansk were not satisfied. The Ukrainian minority in the Don was given national-cultural rights. Other agreements between the two countries were signed as well. Trade began between the Don and the Ukrainian State. The Ukrainian government sold ammunition and arms to the Don Cossacks. Maksym Slavinsky and then Gen K. Seredyn acted as Ukraine’s diplomatic representatives in the region, while Gen A. Cheriachukin, who held the title ‘Ataman of the Winter Settlement’ (stanytsia) was the Don envoy in Kyiv. Under the Directory of the Ukrainian National Republic, relations between the Don and Ukraine became tenuous: the only common action was a request for aid in February 1919 from Ukraine, the Don, the Kuban, and Belarus to the Allied Command in Odesa. In 1919–20 the two countries and their governments went their separate ways: Ukraine tried to defend its independence alone, while the Don became the stronghold of the White Russian movement.

Ukrainian colonies in the Don region. Ukrainians began to settle in the Don region in the 16th century, before the Don Cossacks migrated from the upper to the lower Don River. The name of the Don capital—Cherkassk (now Novocherkassk), that is, the Cherkasian (Ukrainian Cossack) town—attests to this fact. According to oral tradition, the town was first a fishing settlement built by Ukrainians. A document of the Polish king Stefan Batory mentions that the Zaporozhian Cossacks had winter homesteads in the Don region by the early 16th century. Many Zaporozhians settled permanently in the region in groups or individually during the 17th century. Eventually Ukrainian peasants also began to migrate into the chernozem Don steppes, which were almost uncultivated by the Don Cossacks. In the 17th-18th century the newcomers from Ukraine were admitted as voting members to the Don Military Circle.

In-migration from Ukraine worried the Russian authorities, and they tried to stop it. In 1736 and 1740 Moscow issued orders prohibiting ‘Little Russians’ from living in Cossack stanytsias. In 1763 all cherkasy, that is, arrivals from Ukraine, were ordered enumerated. They turned up in 232 localities. Some of them belonged to landlords. According to the census of 1782, the landlords owned 26,579 peasants, of whom 96 percent were Ukrainian. There were also 7,456 Ukrainian steppe homesteads attached to stanytsias. According to the 1811 census, the Don landlords controlled 76,856 peasants. Most of the Ukrainians living in the stanytsias (stanichnye malorosiiany) were admitted to Cossack ranks and formed four Don stanytsias. Two Cossack regiments, consisting of former stanichnye malorosiiany, formed one stanytsia. Some stanytsias of the ‘Don Cossacks’ of Ukrainian origin were incorporated into the Don Cossack Host.

A new decree by the tsar in 1816 prohibited Don landowners from bringing in peasants from Ukraine. After the abolition of serfdom in 1861 the migration of Ukrainian peasants to the Don region increased considerably. The Selianska Kasa and other peasant associations were formed to buy the lands of large landholders. The Ukrainians were occupied almost exclusively with farming, with the exception of those who settled on the coast, who engaged in fishing. As a result of in-migration the number of outsiders, including Ukrainians, in the Don region increased greatly.

Ukrainian culture in the Don region. Ukrainian influence in the Don region was strongest in the 18th–19th century. The principal agent of Ukrainian culture was the Orthodox church, with the Kyivan Cave Monastery as its center. The Ukrainian influence is apparent in church architecture. Many churches of the time were built in the Ukrainian baroque style—among them, the Cathedral of the Assumption in the Cherkassk stanytsia, the wooden church in Pokrovska sloboda, Saint Demetrius’s Church in Rostov-na-Donu, and Saint Nicholas’s Church and the Church of the Trinity in Tahanrih—as were the residences of the Don Cossack officers. In the 19th century there were over 30 baroque stone buildings in Starocherkasskaia. Liturgical books, iconostases, vestments, and church utensils were either imported from Ukraine or else manufactured according to the Ukrainian patterns. From the mid-19th century the effort to Russify the church in the Don region increased, and church books and articles made in Kyiv were replaced by imports from Moscow.

In the 17th-18th century the Don otamans and officers came to Kyiv on pilgrimages and made large donations to the Kyivan Cave Monastery. Otaman S. Efremov, for example, presented the monastery with a large church luster and was rewarded with a portrait in the cathedral and a panegyric in his honor composed by the monks.

Ukrainians who settled in the Don region brought with them their material culture, which was reflected in their houses and home furnishings, farm tools, farm buildings, fencing, well pulleys, dammed ponds, etc. Until the beginning of the 20th century century Ukrainians in the region dressed in Ukrainian folk costumes. Ceramics, woven coverlets, and decorative weavings and towels (rushnyky) were imported almost exclusively from Ukraine. The Ukrainian language, folk songs, folk customs and rites survived for a long time in the Don region.

The culture of the Ukrainian settlers was reflected to a large extent in the culture of the Don Cossacks. A dwelling in a Cossack settlement was called a kurin, originally a term for a Zaporozhian Cossack unit. Men’s clothes, particularly the uniforms of officers, were entirely Ukrainian until the end of the 18th century, as were the insignia and symbols of authority (the bunchuk [standard with a horsetail top] and bulava [mace]) and the military ranks (otaman, colonel, captain, deputy captain, flag bearer). There was a considerable Ukrainian influence on the Don Cossack language. The most distinctive of the Don dialects—the Lower Don dialect—is based on Ukrainian with an admixture of the Nogay Tatar language. Many Ukrainianisms are used throughout the Don region.

The Ukrainian national movement in the Don region. Tahanrih and Donets counties, which contained the largest Ukrainian populations, were the centers of the Ukrainian national movement. In 1905 peasant unrest spread throughout the region. An organization, remarkable for the time, was formed—the All-Russian Peasant Union—in which the three Mazurenko brothers (Semen Mazurenko; Vasyl Mazurenko; and Yurii Mazurenko), who were Ukrainian, played a prominent role. About 200,000 Ukrainian peasants joined the union. Public meetings called by the Mazurenkos in the larger villages and districts demanded among other things the right ‘to speak, write, and read in one’s native tongue: for us, the Little Russian tongue.’ Organizers of the All-Ukrainian Peasant Congress in 1905 counted the region as one of the six territories with a Ukrainian minority and made provisions for its representation. The rural districts that wanted to ‘join Ukraine’ were to send delegates to the congress. The congress did not take place, because the key organizers were arrested.

In 1905 a Ukrainian Hromada was set up in Tahanrih. A drama group survived for ten years and staged many Ukrainian plays.

During the Revolution of 1917 Ukrainian patriots, mostly teachers, toured the villages to propagate the idea of Ukrainian statehood. In 1918 the Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs subsidized Ukrainian organizations and publications in the Don region. When the Soviet regime became established in the Don region in the 1920s, Ukrainization was partly introduced, primarily in public education. In Tahanrih Ukrainian instructors worked in the department of people’s education and in the union of school workers. In the mid-1930s the Ukrainization campaign was stopped. The almost complete absence of an urban intelligentsia accounted for the low level of national consciousness among the Ukrainians of the Don region. Today the Ukrainian population of the Don region and the Russian Federation as a whole is deprived of even minimal cultural rights, and Russification has advanced rapidly, particularly in the cities.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Sukhorukov, V. Istoricheskoe opisanie zemli Voiska Donskogo, 1–2 (Novocherkassk 1867–72)

Donskie dela, 1–5 (Saint Petersburg 1898–1912)

Svatikov, S. Rossiia i Don (Prague 1924)

Hermaize, O. ‘Ukraïna ta Din v 17 v.,’ Zapysky Kyïvs'koho instytutu narodnoï osvity, 3 (Kyiv 1928)

Doroshenko, D. Istoriia Ukraïny 1917–1923, 2 (Uzhhorod 1930; repr, New York 1955)

Simoleit, S. Die Donkosaken und ihr Land (Königsberg 1930)

Tragediia kazachestva, 1–3 (Prague–Paris 1933–6)

Bolotenko, O. Kozatstvo i Ukraïna (Toronto 1950)

Miller, M. ‘Tretii tsentr Rusy. Taniia v svitli arkheolohichnykh materiialiv,’ Zbirnyk UVAN, 1 (New York 1952)

Stetsiuk, K. Narodni rukhy na Livoberezhzhi i Slobids'kii Ukraïni v 50-70-ykh rokakh XVII st. (Kyiv 1960)

Bronshtein, A. Zemlia Donskaia v XVIII veke (Rostov-na-Donu 1961)

Popov, M. Azovskoe padenie (Moscow 1961)

Pod''iapol'skaia, E. Vosstanie Bulavina 1707-1709 (Moscow 1962)

Gvingidze, O. Brat'ia Gruzinovy (Tbilisi 1965)

Volodymyr Kubijovyč, Mykhailo Miller, Vasyl Markus, Oleksander Ohloblyn

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 1 (1984).]

.jpg)