Crimea

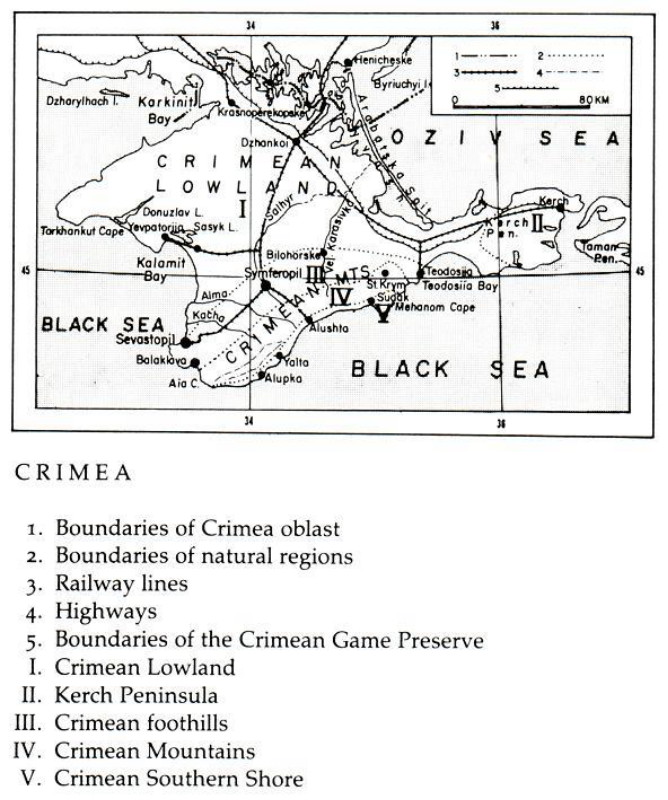

Crimea (Ukrainian: Крим; Krym; Crimean Tatar: Qırım; Greek: Taurica, Chersonese). (Map: Crimea.) The most southerly part of Ukraine, the Crimea is an irregular quadrangular peninsula situated between the Black Sea (in the west and south) and the Sea of Azov (in the east). It has a breadth of 200 km north to south, a maximum length of 320 km east to west, and an area of 27,000 sq km. It is connected to the mainland by the narrow, 7 km Perekop Isthmus, which is flanked by Karkinitska Bay in the west and Syvash Lake in the east. In the east the Crimea is separated from the Kuban (the Taman Peninsula) by the Kerch Strait.

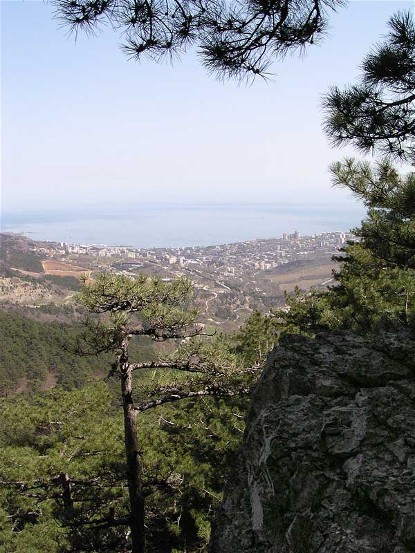

The Crimea consists of two very different parts—the semiarid, treeless steppe of the Crimean Lowland in the north and the Crimean Mountains in the south. The Crimean steppe, with its temperate-continental climate and steppe soils and vegetation, is a continuation of the Ukrainian steppe and together with the Kerch Peninsula occupies four-fifths of the Crimea’s territory. The Crimean Mountains consist of a narrow range of foothills and a low mountain chain covered with forests and high pastures. Below the mountains in the south is a narrow (2–12 km) coastal lowland, the Crimean southern shore, with a Mediterranean climate and vegetation.

The Crimea owes its importance largely to its convenient location on the borders of Ukraine, Caucasia, and the two seas that connect it with the mouths of large rivers, such as the Dnipro River, Dnister River, Don River, Danube River, and Kuban River, with other countries on the Black Sea, and with the Mediterranean Sea. As a result of these factors, the Crimea’s protrusion into the sea, and its good natural harbors, the peninsula constitutes an outpost that controls the Black Sea, particularly its northern part. For this reason, in the past the Crimea was often dominated politically and culturally by seafaring peoples of southern states and was influenced by the states that controlled the Ukrainian mainland. These forces struggled for centuries for control over the Crimea. The peninsula itself was too small to take advantage of its favorable location and organize a strong, independent state. Usually it was the object of contention between large states. The Crimea was rarely politically unified and never ethnically uniform, for its northern part was closely tied to the peoples on the mainland, while its southern part was colonized by Mediterranean peoples. Some descendants of various nomadic peoples that roamed the Ukrainian steppes over the centuries found refuge in the Crimean Mountains.

Because of its geographical location, the Crimea has the most ancient and richest history of all the regions of Ukraine. Control of the Crimea is crucially important for Ukraine as it gives ready and safe access to the Black Sea, the Sea of Azov, the Kuban, and Caucasia, as well as provides a secure southern border.

From 1954 to 1991 the Crimea has constituted Crimea oblast of the Ukrainian SSR; after 1991 it became the Autonomous Republic of Crimea within Ukraine; in 2014 the Crimea was invaded and occupied by the Russian Federation, an act not recognized internationally. Before the invasion at the start of 2014 its permanent population was 2,342,000, of which 1,584,000 was urban and 758,000 rural. The Crimea comprised two administrative entities: the Autonomous Republic of Crimea with its 14 raions and the district of Sevastopol; within them they contained, respectively, 16 and 2 cities, 56 and 1 towns (smt), and 243 and 4 rural councils.

History. The earliest known settlements in the Crimea date back to the Middle Paleolithic Period, about 100,000 years ago. They belonged to the Neanderthal man. Many Neanderthal relics have been uncovered in caves such as Kiik-Koba, Shaitan-Koba, or the Zaskelna archeological site. A burial of a Cro-Magnon child with some Neanderthal features discovered at the Starosilia archeological site near Bakhchysarai suggests that for a period of time at the end of the Mousterian period Neanderthals and Cro-Magnons lived in close proximity in the Crimea and even occasionally interbred. In the Bronze Age (2,000–800 BC) an Indo-European population appeared in the Crimea and engaged in herding and farming. The earliest historical population in the Crimea was the Cimmerians, probably of Iranian descent, who came in the first centuries of the first millennium BC. They were forced out to Asia Minor by the Scythians in the 7th century BC. Cimmerian remnants settled in the Crimean Mountains until the end of the ancient period and, likely, were called Taurians. In the 7th century BC the Greeks appeared on the Crimean coast and a century later began to found colonies: the ancient states on the northern Black Sea coast. There they were joined by maritime Jewish merchants. The most successful colonies were Chersonese Taurica, Panticapaeum, and Theodosia. From the 5th century BC until the 4th century AD the Bosporan Kingdom, with Panticapaeum as capital, controlled the eastern Crimea. In the 3rd – 2nd century BC the remnants of the Scythians, who were forced from the steppes by the Sarmatians, had their own kingdom in the Crimean steppe, with its capital at Neapolis, now the city of Simferopol. The kingdom collapsed in the 2nd century BC under the pressure of Chersonese Taurica and the Alans. Remnants of the Alans survived in the Crimea until the 10th century in the vicinity of Fula (Chufut-Kaleh). In the second half of the 1st century BC the Bosporan Kingdom became a vassal state of the Romans, who controlled all of the Crimean coast and had garrisons in the larger towns and a fleet in Chersonese Taurica. With interruptions, Roman domination of the Crimea continued to the end of the 4th century AD. Thus, in the first centuries AD the Crimea belonged to three states: the Bosporan Kingdom, the republic of Chersonese Taurica, and the Scythian state. In the 3rd century the Goths (who became known as the Ostrogoths) invaded the Crimea, and in the 5th century they were forced from the steppes by the Huns into the mountains.

The Huns destroyed the Scythian state and Bosporan Kingdom and caused the downfall of the Crimea. Panticapaeum declined. At the end of the 5th century the Crimean coast (cities of Chersonese Taurica, Simvolon [present-day Balaklava], Gorzuvita [present-day Hurzuf], Alushton [present-day Alushta], and Bospor [present-day Kerch]) came under the rule of the Byzantine Empire. The empire also offered protection to the Gothic-Alanic domain in the mountainous southwest by helping fortify their Kirk Yer, Esi Kermen and Doros, later re-named Mangup, and provided a bishop for the Crimea’s eparchy of Gothia). A century later most of the Crimea was captured by the Turkic-speaking Khazars, who made Sugdaea (now Sudak) their Crimean administrative center. Byzantium re-established its rule only at the end of the 9th century. It was then that the Karaites (anti-rabbinic Jewish sectarians) arrived from Persia via the Land of Israel and western Anatolia, settling initially in Theodosia. At that time the southwestern part of the peninsula was the most populated region. Chersonese Taurica, the largest city of the Crimea, and several small feudal principalities were situated here. Another important city was Sugdaea on the southeastern coast.

The influx of Slavs into the Crimea began probably in the 4th century, following the Goths, and intensified in the 6th century. In the 6th–10th centuries Greco-Byzantine Crimea, particularly Chersonese Taurica, played an important role in the spread of Christianity, which was established in the Crimea in the 3rd–4th century, and of higher culture to the neighboring lands of Kyiv (see Christianization of Ukraine), Khazaria, and Subcaucasia. For a time the Crimea mediated between Kyivan Rus’ and the Byzantine Empire. The Kyivan Prince Ihor and Prince Sviatoslav I Ihorovych the Conqueror, whose realm bordered on the Crimea in the south and east, tried to gain control over it by holding Kerch Peninsula. Volodymyr the Great captured Chersonese Taurica in 988. In the 10th–12th century the eastern part of the Crimea belonged to Tmutorokan principality, which was part of the Kyivan Rus’ state. Kyiv’s hold over the Crimea was loosened by the invasions of the Pechenegs and Cumans, who even controlled a part of the Crimea for a period. Vigorous trade between the Crimea and Kyiv, which included the export of Crimean salt, followed two routes: the ancient route along the Dnipro River and the Black Sea, and a newer route from the lower Dnipro via the steppe and the Perekop Isthmus.

When the Crusaders took Constantinople (1203, 1204), the Byzantine Empire lost its influence in the Crimea. In the mid-13th century Venetian and, more importantly, Genoese trade colonies were established in the Crimea as the western terminus of the Silk Road. The leading colony was Kaffa (in Italian, Caffa, now Teodosiia); other important colonies were Cembalo (Balaklava), Soldaia (Sudak), and Cerchio (former Bospor, now Kerch). Chersonese Taurica declined completely in this period. In its place emerged the kingdom of Theodoro, a remnant of the Empire of Trebizond (1204), a successor rump state of the Byzantine Empire. It was relegated to its port of Avlita and above it the fortress Kalamita (present-day Inkerman) and its fortified capital to the east, Mangup. Its inhabitants, including Greeks and Hellenized descendants of the Taurians, Scythians, Sarmatians, Goths, Alans, Jews (later known as Krymchaks), Karaites, Slavs, and Armenians, were ruled by an Armenian dynasty from Trebizond and worshipped in the eparchy of Gothia. In the 14th century, with the fall of the Armenian state, many Armenians appeared.

1223 –1783. From the mid-13th century the Crimea, except for the Italian colonies, which remained self-governing for a long time, was seized by the Tatars of the Golden Horde. The geographical position of the Crimea favored the resistance of the Crimean Tatars—led by Nogai (1290–1301), Mamai (1362–82), and Edigei (beginning of the 15th century)—to the central authority in Sarai. This contributed to the disintegration of the Golden Horde and the formation in the Crimea in 1449 of a separate state known as the Crimean Khanate, under the leadership of the Girei dynasty, which held power until 1783. Besides the Crimea the khanate controlled the lower Dnipro River, the steppes along the coast of the Sea of Azov, and the western part of the Kuban region.

The first capital of the Crimean Khanate was Solkhat / Kirim (now Staryi Krym) in the foothills of the east. By the mid-fifteenth century the capital was relocated westward to the mountain-top fortress of Kirk Yer, with the khan’s residential palace in the Churuk-Su River valley below at Salachik (today Starosillia). In the second half of the 15th century, 2 to 3 km downstream from Salachik, the more spatious Bakhchysarai became the new capital of the Crimean Khanate and the seat of the mufti, the head of the Moslem clergy. Turkic as spoken by the urban Crimean Tatars became the language of commerce and adopted by the Jews (Krymchaks), the Karaites, and some Greeks. The expansion of the Ottoman Empire changed the geopolitical configuration of the Crimea. In 1474 Turkey captured the Italian colonies in the southern Crimea, destroyed the Crimean Tatar vassal state of Theodoro in 1475, and established direct rule over the south coastal cities. Their Italian names were changed to Turkish: Kalamita became Inkerman, Cembalo — Baliklava (later, Balaklava), Soldaia — Sudak, Cherchio — Kerç (today’s Kerch) with a fort at Eni-Kale, and Caffa became Kefe. In 1478 the Crimean Khanate recognized the supremacy of the Ottoman Empire. The Crimean Tatars, having come under the cultural influence of the Turks, adopted their alphabet and literature. The Nogay Tatars, including the Bilhorod, Edissan, Edichkul, and Dzhambuiluk hordes, which lived in the steppes north of the peninsula and along the Black Sea, were the vassals of the Crimean khan. (See Bilhorod Horde, Budzhak Horde, Budzhak Tatars.) They were pastoralists but also conducted raids.

The Crimean Tatars practiced animal husbandry, agriculture, orcharding, and artisanry. They also invaded neighboring lands, particularly Ukraine, plundering and inflicting heavy losses on them. Having signed a treaty with Muscovy’s Ivan III and having secured the support of Turkey, the Crimean Tatars sacked Kyiv in 1482. Tatar forces invaded Podilia, the Kyiv region, Volhynia, Galicia, and the Chernihiv region almost annually, destroying the towns and villages and seizing inhabitants, whom they later sold at slave markets. In the 16th century the Ukrainian Cossacks came to the defense of the population, and by the beginning of the 17th century they took the offensive against the Tatars. Under Hetman Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny the Cossacks sacked Perekop and Kaffa (1616). Eventually peace was established, and on 24 December 1624 the Tatar khan concluded an alliance against Turkey with Hetman Mykhailo Doroshenko. The Cossacks helped Khan Shagin-Girei to destroy the Turkish fleet. In the end, however, the Turkish faction won the upper hand, and after Doroshenko’s death near Bakhchysarai in 1628 his Cossacks were forced to retreat from the Crimea.

In 1648 Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky concluded an alliance with the Crimean khan Islam-Girei III (1644–54), and the Tatar army helped Khmelnytsky defeat the Poles at the Battle of Korsun (1648) and the Battle of Zboriv (1649) during the Cossack-Polish War. To prevent Khmelnytsky’s complete victory and the rise of a strong Ukrainian Cossack state, the Crimean khan forced Khmelnytsky to accept peace with Poland after the Battle of Zboriv (see Treaty of Zboriv) and the siege of Zhvanets (1653; see Treaty of Bila Tserkva) and betrayed him at the Battle of Berestechko (1651). The Crimean Tatars also plundered Ukraine and took many people into captivity (yasyr) on their return home. This forced Khmelnytsky to change allies and to sign the Pereiaslav Treaty of 1654 with Muscovy. Hetman Ivan Vyhovsky renewed the alliance with the Crimean khan, and the Tatars took part in the Battle of Konotop (1659). Hetman Petro Doroshenko had good relations with the Crimea, while the Zaporozhian Cossacks, under the leadership of Ivan Sirko, pursued for the most part a policy of hostility towards the Tatars. Tatar aggression in Right-Bank Ukraine during the period 1660–80 ruled out any possibility of Ukrainian-Tatar co-operation. In the Treaty of Bakhchysarai (1681) the Crimean Tatars were forced to make concessions to Muscovy.

After the Eternal Peace of 1686 between Poland and Muscovy, Ukrainian and Crimean interests again began to converge. An influential pro-Crimean orientation, supported by hetmans Ivan Samoilovych and, at first, Ivan Mazepa arose, in spite of the fact that the hetman forces had to take part in Muscovy’s Crimean campaigns of 1687 and 1689. The Cossack leaders Vasyl Kochubei and Petro Petryk pursued a friendly policy towards the Crimea and Turkey. In 1692 Petryk concluded an alliance against Muscovy and Poland with the Crimean khan, who recognized him as the hetman of Ukraine. But the khan’s plans did not succeed, and Petryk had to settle for the role of ‘hetman’ in khanate-controlled Ukraine. In putting together a coalition against Muscovy, Hetman Pylyp Orlyk concluded an alliance with the Crimean khan in 1711 but did not receive the help he expected; instead, the Tatars plundered Right-Bank Ukraine and Slobidska Ukraine in 1711–14. This was the last attempt at Ukrainian-Tatar co-operation.

In the 18th century the Cossacks helped Russia wrest control of the Black Sea coast from Turkey and the Crimea. The ‘alliance of eternal friendship,’ signed by Russia and the Crimean Khanate in Qarasubazar (now Bilohirsk) in 1772, and Turkey’s recognition of Crimean independence in the Peace Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca in 1774 were diplomatic victories in Russia’s strategy leading to the annexation of the Crimea in 1783.

During the 18th century the Hetman state and the Zaporozhian Sich had economic links with the Crimea. Ukraine imported Crimean products such as fish, salt, vegetables, textiles, and manufactured articles and exported to the Crimea grain, manufactured articles, and other goods. Trade with Turkey also flowed through the Crimea.

1783–1917. In the Russian Empire the Crimea became a part of the territory of New Russia gubernia and then, in 1802, of Tavriia gubernia. Russia immediately took advantage of the Crimea’s strategic importance and built the port and fortress of Sevastopol (1783), which became the home base of the Black Sea Fleet. The administration of this territory was centrally located at Simferopol (1784, re-named from the Tatar Ak-Mechet, near the ancient Neapolis). The old Tatar capital Solkhat (now Staryi Krym) was re-named Levkopol (1784), and Kezlev (formerly the ancient Greek colony of Kerkinitis) was changed to Yevpatoriia (1784). This Hellenization of place names demonstrated the Imperial Russian claim to the heritage of the Byzantine Empire, the geopolitical ‘protection of Orthodox Christians’ in the Ottoman Empire, the validation of its territorial claim to the Crimea and of civilizational respectability.

Initially, the compliant leadership of the Crimean Tatars, the Islamic clergy, and the Tatar nobility were socially accommodated in the Russian hereditary estates and kept their properties. Aristocratic Russian families from the north, attracted by Crimea’s mild climate and exotic cultural and physical landscape, had handsome residences and palaces built there: the Prince Naryshkin residence (1826–27) in Simferopol, the Potocki manor (1834) at Livadia near Yalta, the Vorontsov palace (1833–48) at Alupka, and the Golitsyn palace (1836) at Gaspra. Beginning in 1850, however, the Russian Orthodox ideologists undertook restoration of ‘ancient holy places in Crimean Mountains,’ the ‘return’ of Crimean Tatars (who were presumably assimilated Greeks and others) to their alleged ancient Orthodox faith, the conversion of some mosques to churches, and the construction of monumental cathedrals: the Aleksandr Nevsky Cathedral in Simferopol (1829–81), the Saint Vladimir Equal to the Apostles in Sevastopol (1858–88), the Aleksandr Nevsky Cathedral in Yalta (1891–1902), the Church of Christ’s Resurrection in Foros (1892), the Church of Saint Catherine in Teodosiia (1892), the Church of the Holy Mother of God the Protectress in Sevastopol (1892-1905), and Church of Saint Nicholas the Wonder Worker in Yevpatoriia (1893–99). Religious and economic repression of the majority of Crimean Tatars, during which they were forced to forfeit most of their lands to Russian landlords, caused a mass migration to Turkey, particularly in the first years of Russian rule and after the Crimean War (1853–6). At the same time Ukrainian and Russian peasants, as well as Germans, Bulgarians, and other colonists, flowed into the Crimea, particularly into the steppe region. From the 1870s Russians moved increasingly into the towns and resorts on the Crimean southern shore. By the beginning of the 20th century the Crimea was an ethnically mixed land inhabited by Russians, Ukrainians, and Crimean Tatars.

The salubrious climate and picturesque settings of the Crimean southern shore attracted the Russian Empire’s leading creative talent, including national poets: the Polish Adam Mickiewicz (‘the Crimean Sonnets’), the Russian Aleksandr Pushkin (‘Fountain of Bakhchysarai’) and the Ukrainian Lesia Ukrainka (her two cycles, ‘Crimean Memories’ and ‘Crimean Echoes’). In the 1880s the Crimea also became the birthplace of the national revival of the Crimean Tatars, ushered in through the ‘new method’ schools introduced in Bakhchysarai by Ismail bey Gaspirali (Gasprinsky). By the turn of the century, it spawned a new generation of intellectuals, known as the Young Tatars, who moved beyond Gaspirali’s cultural interests to social and political concerns. By then, the Crimea was steeped in a Russian mythology that saw it as a birthplace of Russian Orthodoxy, a symbol of military glory, the muse of cherished Russian writers and artists, and a playground of the elite.

1917–19. With the outbreak of the February Revolution of 1917, four political tendencies competed in the Crimea. 1) The Crimean Tatar movement aspired to Crimean autonomy and eventual sovereignty by a) establishing the Milli Firka (a party both nationalist and socialist in orientation) in July 1917, followed by b) convening of the Kurultai (the Crimean Tatar Parliament, 8 December 1917, at the former palace of the khans in Bakhchysarai where it adopted ‘basic laws’) and c) declaring the formation of an independent Crimean Democratic Republic (25 December 1917, headed by its National Directorate, in Simferopol). 2) The Russian orientation favored the Crimea’s continued allegiance to Russia; opposing the Bolshevik coup in Petrograd, on the initiative of the Socialist Revolutionary Party of Russia, it established the Crimean Provincial Assembly (November 1917, in Simferopol), with multi-party delegates from all ethnicities, including some Muslim clergy. 3) The Ukrainian advocacy for the Crimea’s incorporation into Ukraine was, at first, ambivalent. 4) The Bolsheviks became a dominant force in Sevastopol and a contender for the Crimea after November 1917.

Initially, the Ukrainian Central Rada, while negotiating with the Provisional Government of Russia for its autonomous territory based on ethnic majority, did not treat the Crimea as part of Ukraine in its Third Universal of the Central Rada (19 November 1917). However, the Third All-Ukrainian Military Congress in Kyiv (2–12 November 1917) decided to Ukrainianize the Black Sea Fleet (where 70 to 80 percent of the sailors were ethnic Ukrainians); upon the declaration of the Third Universal of the Central Rada nearly one-half of the ships of the Black Sea Fleet raised the Ukrainian flag. By the beginning of 1918 the Ukrainians of Sevastopol established the first self-funded 6-grade Ukrainian elementary school.

After the Bolsheviks overthrew the Provisional Government in Petrograd, the Central Rada in Kyiv (having survived a similar coup) proclaimed Ukraine’s independence (22 January 1918) and saw the need to control the Crimea and the Black Sea Fleet. The Bolsheviks, having seized control of Sevastopol (on 14 January 1918) and slaughtered some 250 Black Sea Fleet officers (22–23 February 1918), set out to conquer the rest of the Crimea. Thus threatened, the Crimean Tatar Republic’s National Directorate in Simferopol reached an accord with the Ukrainian National Republic to become part of Ukraine. Even so, by April 1918, the Bolsheviks occupied the Crimea to establish the Soviet Republic of Tavrida. Ukrainian forces commanded by Col Petro Bolbochan responded by taking Simferopol and Bakhchysarai on 25 April 1918, but the German command, now in control, forced him to abandon the Crimea. This led to the loss of the Black Sea Fleet, which had already raised the Ukrainian flag on its ships (29 April 1918) and the removal of Ukrainians from Sevastopol.

With German support, General Matvei (Suleyman bey) Sulkevich (a former tsarist general descended from a Lithuanian Tatar) formed a government in which there was strong anti-Ukrainian sentiment (among other things, this government closed all pro-Ukrainian newspapers). The Ukrainian communities in the Crimea, headquartered in Simferopol, resisted Sulkevich’s government and these developments provoked the Ukrainian government to blockade the Crimea. The Crimean government was forced to negotiate in Kyiv in October 1918 and to adopt a preliminary treaty by which the Crimea was to become an autonomous part of Ukraine, with its own diet, territorial army, and administration as well as a permanent state secretary in the Council of National Ministers of the Ukrainian National Republic. The treaty was never put into effect, because as soon as the Germans retreated the Crimea fell into the hands of right-wing Russian forces, which were supported by the expeditionary forces of the Allied Powers. In April 1919 the Crimea was briefly occupied by the Bolsheviks (headed by Vladimir Lenin’s brother, Dmitrii Ulianov), who were forced out by General Anton Denikin in June. In 1920 the Crimea served as General Petr Wrangel’s main base.

1920-91. In November 1920 the Bolshevik armies occupied the Crimea for the third time. As part of War Communism, the Crimean Revolutionary Committee, led by Béla Kun, forced the inhabitants into submission with a bloody terror campaign. Powerful opposition led Moscow to soften its policy. On 18 October 1921 the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was proclaimed. It was made part of the RSFSR, rather than the Ukrainian SSR, although the Crimea shared no land border with Russia. The Ukrainian school in Sevastopol was closed, and in the beginning of 1922 re-opened as a Russian school. Although the Crimea was granted territorial autonomy as a multiethnic (not specifically Tatar) entity and its pursuit of foreign affairs (requested by the Crimean Tatars) was denied, 4 of the 13 commissars in the Crimea’s government were Crimean Tatar Bolsheviks. Beginning in 1924, Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazi Jews were resettled from the Ukrainian SSR to help develop steppe Crimea by establishing 16 collective farms (kibbutzim); the (Jewish) American Joint Distribution Committee assisted with the provision of farm equipment. That year, 10 administrative (rural) raions of the Crimea were increased to 16, of which 5 were designated as Tatar, 1 as German and 1 as Jewish; the remaining were not designated, but within them the largest number (144) of their self-governing village councils were designated Crimean Tatar, 106 Russian and, finally in 1927, only 3 Ukrainian. Also in 1927 a Ukrainian school, a club, and a library were established in Simferopol to cater to the Ukrainian community. Upon the urging of the Ukrainian section of the Crimean National Minority Cultures Council, Ukrainian schools were set up in areas with Ukrainian majorities, where only Ukrainian was spoken, to facilitate their education; by 1930 there were 17 Ukrainian schools, reaching 40 by 1931.

In the 1920s the Crimean Tatars were allowed to foster their culture in the Crimean ASSR. By 1930, a common Crimean Tatar grammar (based on the peninsula’s central mountain dialect which evolved during the era of the Crimean Khanate), was adopted and taught at 387 elementary schools.

In 1933 a policy of Russification was introduced, and the Crimean Tatars were persecuted. The Ukrainian language lost its standing in the Crimea, and all but one Ukrainian school were converted to Russian. Religion was attacked and churches and mosques were closed.

During the Second World War the Crimea was occupied by the Germans for two and one-half years. The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalist covert task force groups helped revive Ukrainian communities in the Crimea by establishing the Ukrainian National Committee, the Ukrainian theater, and Ukrainian schools. Since Turkey was an ally of Germany, the Crimean Tatars were handled with care and drawn into German military service. However, Adolph Hitler planned to include the Crimea in the Third Reich as the former land of the Germanic Goths, and turned to exploit, enslave, and depopulate the peninsula and kill its Jews (the Ashkenazi and the Krymchaks). This evoked resistance from the population, including many Crimean Tatars.

After the war the Soviets accused the Crimean Tatar population of ‘treason and collaboration with the Germans’ and deported them to forced labor colonies of Central Asia (mainly in the Uzbek SSR) or Asiatic parts of the RSFSR. Along the way some 20–25 percent of the Crimean Tatars perished; more died at forced labor camps. This ethnic cleansing, a form of genocide the Crimean Tatars called ‘Sürgünlik’ (exile), became their collective memory and political pillar of identity. Other of the Crimea’s national minorities (Armenians, Bulgarians, Greeks, and Germans) were also removed. On 30 June 1945 the Crimean ASSR was abolished, and the region was turned into an ordinary oblast of the RSFSR. Tatar and German place names were changed to unrelated Russian or Soviet names. The deported Crimean Tatars were replaced partly by Ukrainians, some from the regions of Western Ukraine that, before 1939, were in Poland and some from other rural parts of Ukraine, and partly by Russians, mostly from central RSFSR.

By decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR the Crimea was transferred from the RSFSR to the Ukrainian SSR on 19 February 1954. This was done to facilitate economic development of the Crimea: the supply of materials and labor by the mainland portion of the Ukrainian SSR and the provision of water from the Dnipro River via the proposed North Crimean Canal. This administrative change also triggered a brief attempt to ‘Ukrainianize’ the Crimea by: 1) introducing the instruction of Ukrainian language and literature in the schools of the Crimea and establishing a department to train teachers of Ukrainian language and literature at the Crimean State Pedagogical Institute; 2) translating several programs on local radio and television into Ukrainian; 3) providing a Ukrainian-language version of the flagship newspaper, Krymskaia Pravda (1918–), as Kryms’ka Pravda (1955–59), the Ukrainian language Radians’kyi Krym (1955–59), as well as other publications; and 4) introducing public signage in Ukrainian. The number of students attending Ukrainian language classes increased from 619 in 1955–6 to 19,766 in 1958–9 (or 12.2 percent of the total enrolment, about one-half of the share of ethnic Ukrainians in the Crimea’s population. Local Russian opposition to these measures, however, as well as the introduction (1959) of obligatory instruction in Russian and voluntary choice of language for schooling resulted in a decline in the attendance in Ukrainian schools; by 1970–1 there was only one Ukrainian language school left in Simferopol, attended by 412 students. In 1959 the Crimean Oblast Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine also decided to cease the publication of its Ukrainian language newspaper Radians’kyi Krym and the Ukrainian language versions: Bloknot ahitatora and Vynohradarstvo i sadivnytstvo Krymu. By 1988 there were no Ukrainian schools, clubs, radio or television programs, and no publications in Ukrainian in the Crimea; the exceptions were some villages, where some spoken Ukrainian could still be heard.

Meanwhile, the decree of 28 April 1956 forbade the Crimean Tatars to return to the Crimea. This prohibition was in effect until 1988, shortly before Ukraine proclaimed independence in 1991, despite the decree of 5 September 1960 which exonerated the Crimean Tatars from collaboration with the Germans. Ukrainian dissidents (like Petro Grigorenko [Hryhorenko], Sviatoslav Karavansky, and Viacheslav Chornovil) spoke out in support of the Crimean Tatar community’s campaign for the right to return to the Crimea.

During Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika, the principle of the freedom of expression allowed for the reopening of churches and the proliferation of religious sects, with similar trends in the Crimea. As centrifugal forces spawned declarations of sovereignty in various parts of the USSR, regionalism also gained strength in the Crimea. In January 1991 the Supreme Soviet of the Crimea held a referendum and in February 1991, the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR ratified the change of status of the Crimea from an oblast to that of an Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. Following the proclamation of Ukraine’s independence (24 August 1991) and the referendum that confirmed it (1 December 1991), the name was simplified to the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, or simply Republic of Crimea.

1991–2014. Immediately after Ukraine’s independence, the Crimea became a bone of contention between the Russian Federation and Ukraine. Despite the vote in favor of Ukraine’s independence in the Crimea (54.19 percent), there was a strong Russian undercurrent in the Crimea for separation from Ukraine and closer relations, if not reunion, with the Russian Federation. Supported by the officers of the Russia-controlled Black Sea Fleet and some Russian politicians in Moscow, Crimean legislators passed various resolutions, including the demand for a dual (Ukrainian-Russian) citizenship, but backed away from holding a referendum on their proposed new constitution of virtual independence (May 1992), when it was resolutely opposed in Kyiv. Continuing Russian pressure (declarations that Sevastopol, the base of the Black Sea Fleet, is Russian), required the appeal of Ukraine to the Security Council of the United Nations (June 1993) to prevent Russian aggression. To ease the tensions, the two governments signed an interim treaty, establishing a joint Russo-Ukrainian Black Sea Fleet (under Soviet Navy flag, with a Russian admiral, and with the majority of personnel adopting Russian citizenship). A full-scale partition agreement was not reached until 1997, when Ukraine agreed to lease major parts of its facilities to the Russian Black Sea Fleet until 2017.

In January 1994 Yurii Meshkov was elected the first president of the Crimea. Pursuing a pro-Russian agenda, he held a referendum (March 1994) and then ushered through the adoption in the Crimean parliament of the proposed 1992 constitution; vigorous opposition from Kyiv led to its suspension. Nevertheless, with the support of Crimean politicians, Russian consular offices in the Crimea began to issue applications for Russian citizenship (March 1995). The Ukrainian government protested, abolished the post of the president of the Crimea, annulled the Crimean constitution of 1992, and requested that Crimean legislators revise the constitution so that it would harmonize with the Ukrainian constitution. Deposed from his post, Yurii Meshkov left the Crimea for Moscow. In an attempt to curb the autonomist and separatist aspirations of some part of the Crimea’s population, the Ukrainian government replaced him (in 1994) with its appointee Anatolii Franchuk. Crimea’s autonomous status was re-affirmed in 1996 with the ratification of Ukraine’s current constitution, which designated Crimea as the ‘Autonomous Republic of Crimea,’ but also an ‘inseparable constituent part of Ukraine.’ In it, the Crimea was granted ‘extensive home rule.’

Meanwhile, the Crimean Tatars worked to develop their civic organizations: their national assembly, the Kurultai (renewed 26–30 June 1991), and their supreme plenipotentiary representative and executive body of the Crimean Tatar people, the Mejlis (not officially recognized until 1999; led from 1991 by Mustafa Jemilev). In this the Crimean Tatars were supported by the Ukrainian political organization the Popular Movement of Ukraine (Rukh) and in turn were loyal supporters of Ukraine. Locally, the Crimean Tatars who returned from exile to the Crimea were harassed by Russian chauvinists, denied claims to their former homes and neglected by local authorities for housing and services. Many resorted to building shanties on vacant public land. They succeeded in establishing a national theater, a symphony orchestra, a university, a television channel and radio station, and published a four-volume history of the Crimean Tatar nation.

Ukrainian government provided weak support for Ukrainian culture and education in the Crimea. In 1997 there were only one Ukrainian-language newspaper, Kryms’ka svitlytsia (established in Simferopol in 1992, sponsored by the All-Ukrainian ‘Prosvita’ Society and the Crimean Center ‘Ukrainskyi Dim’). Kryms'ka svitlytsia featured both Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar poets and writers espousing love of the country and common cause; by contrast, the Russian establishment Krymskaia Pravda was hostile to the Crimean Tatars and the Ukrainian government in Kyiv. There was one Ukrainian state music-drama theater, one Ukrainian school and 23 Ukrainian classes in Russian schools. Russian was nearly the exclusive mode of instruction of pupils in day secondary education (99.5 percent in 1995/96, giving way to 93 percent by 2005/06 [with Ukrainian increasing from 0.1 to 5 percent and Tatar to 2 percent]. That year, of the 583 schools in the Crimea, only 4 had Ukrainian language of instruction; of the 23.4 percent of pupils who declared themselves ethnic Ukrainian, only 0.7 percent had lessons taught in Ukrainian.

Russification was also promoted by the dominant Russian Orthodox church, re-named the Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Moscow Patriarchate (1989). Following Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika and Ukraine’s independence, the church revived its activities and other religious institutions appeared in the Crimea. By 2013 the Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Moscow Partiarchate (in fact, the Russian Orthodox church), which promoted the concept of the ‘Russian World,’ had 595 registered entities (39 percent of all entities and even higher percentage of all adherents), with 3 eparchies, a seminary, and a monastery. The second largest was the Moslem group, catering mainly to the Crimean Tatars, with 403 registered entities (26 percent of the total). The third, a much smaller faith, was the Ukrainian Baptists (77 entities, 5 percent) and the fourth, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Kyiv Patriarchate (an eparchy with 46 entities, including a monastery, 3 percent). The Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox church had only 11 entities (including a theological seminary), the Ukrainian Catholic church, 12, the Roman Catholic church, 14, while the Jewish organizations, 15; Protestant churches included the Fifth Reformed Church, with 12 entities, and the Seventh-Day Adventists, 29; the Jehovah’s Witnesses, 37, and all the others, 281 small entities.

Tensions in the Crimea increased after the election of President Viktor Yushchenko (2005–10), with his overt pro-Ukrainian policies. During his tenure the percentage of pupils in day secondary education with Ukrainian language of instruction increased in the Crimea by 2009/10 to 8 percent (still far below the 24 percent share of Ukrainians in the population); instruction in Russian dipped to 89 percent (still well above the 60.4 percent share of the Russian population). With the Russian Black Sea Fleet based in Sevastopol exerting claims to Ukrainian lighthouses along the Crimean coast, there were fears of armed confrontation; Yushchenko (11 November 2009) called for the Russian Black Sea Fleet to leave Sevastopol by 2017.

In 2010 Viktor Yanukovych won the presidential elections and the Party of Regions won an 80 percent majority in the local elections (31 October) to the parliament of the Crimea. Its pro-Russian policies, implemented by President Yanukovych—the 2010 Ukrainian–Russian treaty that extended the Russian Federation’s lease on the naval facilities in the Crimea until 2042 (with optional five-year renewals) and the official status of Russian as a regional language in the Crimea—quelled separatism.

By contrast, the Euromaidan Revolution in Kyiv (21 November 2013–21 February 2014), followed by an attempt by the Supreme Council of Ukraine to repeal the regional languages law (23 February 2014), and the escape of Yanukovych to the Russian Federation (24 February 2014)—stoked by propaganda from Moscow about a ‘rabid anti-Russian coup’ in Ukraine—re-ignited pro-Russian separatism in the Crimea.

From 2014. The start of Russian movement of troops without insignia to annex the Crimea began on 20 February 2014, as indicated on the Russian medal ‘For the return of the Crimea,’ while Viktor Yanukovych was still president. On 22 February 2014 pro-Russia protesters demonstrated in front of the parliament building in Simferopol; on 23 February, in Sevastopol, the pro-Russia forces ‘elected’ a new mayor and decided to stop paying taxes to the new government in Kyiv; on 25 February, in the Crimean parliament a round-table was held with the participation of deputies from the Russian Federation, urging separation from Ukraine; outside parliament, on 26 February, thousands of pro-Russia and pro-Ukraine protesters clashed in counter-demonstrations. Meanwhile, by 28 February, Russian forces occupied airports and other strategic locations in the Crimea. Gunmen (either armed militants or Russian special forces) occupied the Crimean parliament and, with doors locked, members of parliament elected the pro-Russian Sergei Aksionov as the new Crimean Prime Minister. Aksionov asserted control over the Crimea’s security forces and appealed to the Russian Federation ‘for assistance in guaranteeing peace’ on the peninsula. The Ukrainian National Security and Defence Council, aware of the surrounding Russian forces poised to invade, the lack of Ukrainian military preparedness and no foreign military support, ordered the Ukrainian military in the Crimea to remain in their bases and not fight the Russian forces. On 4 March Russian forces blocked Ukrainian military bases and blockaded Ukrainian warships in the Crimea.

On 6 March, the Crimean Parliament asked the Russian government for the Crimea to become a subject of the Russian Federation with a referendum set for 16 March. The Ukrainian government, the European Union, and the United States of America all challenged the legitimacy of this referendum.

The Crimean authorities claimed the turnout for the referendum (83 percent), and the overwhelming majority of those who voted (95.5 percent) supported the option of joining the Russian Federation. However, BBC reported that most Crimean Tatars and many Ukrainians abstained from the vote; indeed, the Ukrainian World Congress (media release of 8 May 2014) reported the real results on Russia’s Presidential Council for Civil Society and Human Rights posting (which was quickly taken down): 50–60 percent voted for joining the Russian Federation in a 30–50 percent turnout, meaning that only 15–30 percent of the Crimeans were in favor.

Following the referendum, the members of the Supreme Council voted to rename themselves the State Council of the Republic of Crimea and applied to join the Russian Federation. On 18 March 2014 the self-proclaimed Republic of Crimea signed a treaty of accession to the Russian Federation for each of the former regions that composed it: the Republic of Crimea, and Sevastopol as a federal city. Meanwhile, Russian military persuaded some local Ukrainian military to switch sides for their safety and better pay. On 24 March 2014 the Ukrainian government negotiated unimpeded withdrawal of its armed forces from the Crimea; two days later the last Ukrainian military bases and Ukrainian navy ships were seized by Russian troops.

Ukraine continued to claim the Crimea as part of its sovereign territory. Most countries recognized Ukraine’s claim, while the USA, Canada and the European Union sanctioned the Russian Federation for its act of annexation.

Meanwhile, the Russian Federation set out to integrate the Crimea. All residents of the Crimea were urged (18 March) to become citizens of the Russian Federation. Those refusing to do so would lose access to state services and the right to own property. Individuals sympathetic to the Euromaidan Revolution or Ukraine and hostile to Russian annexation (many Crimean Tatars and some Ukrainian and Russian journalists) were persecuted on trumped up charges; others took refuge (as internally displaced persons) in mainland Ukraine. Institutions featuring Ukrainian identity, such as Ukrainian churches, were suppressed. The rouble became parallel tender (24 March) and then the only official tender (1 June 2014). Clocks in the Crimea were switched to Moscow time (29 March). On 3 April 2014, Moscow terminated its agreement concerning the deployment of the Russian Federation’s Black Sea Fleet on (what it no longer considered) the territory of Ukraine and thus the discount it provided on Russian natural gas. A new constitution for the Republic of Crimea was approved (11 April 2014) with regulations analogous to the articles of the Constitution of the Russian Federation. Formally, it listed Russian, Ukrainian, and Crimean Tatar as official languages of the Republic of Crimea; in practice, Russian became mandatory for street signs and for the language of instruction, with other language studies optional. This and the political atmosphere impacted schooling in Crimean Tatar and Ukrainian languages and programs. Whereas in 2013–14 there were 15 Crimean Tatar language schools, 7 Ukrainian-track schools, 175 bilingual (Russian–Ukrainian) or trilingual (Russian–Ukrainian–Crimean Tatar) schools on the peninsula, by 2015–16 teaching in Crimean Tatar and Ukrainian languages was drastically reduced. Only 17 Ukrainian-track classes would be formed throughout the Crimea, none of them at first grade. The prestigious ‘Simferopolska Ukrainska Himnaziia no. 9’ was transformed, under new management, into the Russian-language ‘Simferopolskaia Akademicheskaia Gimnaziia’ while other schools bearing names of prominent Ukrainians were re-named. The Crimean Tatar classes were reduced to 32, with only 3 new first-grade classes, thus encompassing about 11 percent of the total Crimean Tatar school population. Moreover, the Crimean Tatar alphabet, which began its transition to the Latin script in 1997, faces the requirement to return to Cyrillic script. The Crimean Tatar television station ‘ATR’ and sister radio station ‘Meydan’ were forced to shut down, as was its popular newspaper, Avdet (Return) and website ‘Crimean News Agency’; in 2015 they relocated to Kyiv.

Since 2016, the Russian government has funded a concerted effort to educate ‘patriots of the Crimea’ with Russian identity. The Russian Defense Ministry’s Youth Army was being indoctrinated to fight, according to Valentina Potapova, head of the Ukrainian Almenda Center for Civic Education, the enemy: Ukraine, Ukrainians, and the Crimean Tatars.

On 14–25 October 2014 a special population census was conducted in the Crimean Federal District. On 7 May 2015, the phone codes were switched from the Ukrainian to the Russian number system. In July 2016, the Crimea ceased to be a separate federal district and became part of the Southern Federal District of the Russian Federation. The Crimean peninsula, an exclave of the Russian Federation, was physically connected by a multibillion-dollar road–rail link across the Kerch Strait (the Crimean Bridge), becoming operational for road traffic in 2018, and for rail traffic in 2019 (passenger) and 2020 (freight). Between 2014 and the beginning of 2021, according to Federal State Statistics Service in the Crimea and Sevastopol, over 205,000 Russians moved into the Crimea, of whom over 88,000 settled in Sevastopol. Enhanced with a new Kerch to Sevastopol highway, the Crimea became a Russian bulwark to dominate the Black Sea basin and a platform from which to attack Ukraine on 24 February 2022.

Population. (Map: Population Distribution in the Crimea.) At the end of Tatar rule in 1775, the population of the Crimea was 250,000; of this most was composed of Crimean Tatars and one-eighth of Greeks. A few years before their annexation of the Crimea in 1783, the Russians resettled almost all of the Greeks (close to 30,000) from the Crimea to the Mariupol region; the Armenians were also resettled, in the Nakhichevan area of the lower Don region near Rostov-na-Donu. A mass emigration of the Crimean Tatars to Turkey ensued. The population of the Crimea thus fell to 158,000 in 1800, despite the immigration of Ukrainian and Russian settlers. At the beginning of the 19th century the Russian government encouraged Germans, Bulgarians, and other colonists to settle and cultivate the uninhabited lands of Southern Ukraine and the Crimea, particularly the north. A part of the Greeks in the Mariupol region also returned to the Crimea. Consequently, the population increased to 319,000 by 1855. But by 1865 it had fallen to 194,000 because of the Crimean War and a second mass emigration of the Crimean Tatars. A railway constructed in 1875 and the development of resorts on the Crimean southern shore attracted Ukrainian farmers into the steppes and Russians into the cities. By 1897 the population had grown to 565,000 and by 1913 to 729,000. Population changes in the interwar period were influenced by two great famines, in 1921 (see Famine of 1921–3) and 1932–3 (see Famine-Genocide of 1932–3), and the industrialization of the 1930s. In 1940 the population was 1,127,000. The population growth in the Crimea was much greater than in most other parts of Ukraine: from 1897 to 1940 the population of Ukraine increased by 30 percent, while that of the Crimea increased by 107 percent. Among the regions of Ukraine, until the 1930s, the Crimea had the highest percentage of urban population. The Second World War and subsequent deportations (particularly of the Crimean Tatars) reduced the population so that the 1940 level was not regained until early 1957. Table 1 gives the population of the Crimea in various years (in thousands).

The population of the Crimea has grown by less than 50,000 per year, from 2,458,600 in 1989 to 2,500,500 in 1990, 2,549,800 in 1991, 2,596,000 in 1992, 2,638,800 in 1993, and 2,651,700 in 1994. Since the natural increase of the population of the Crimea was small and declining, until it became negative in 1992, most of the annual increases resulted from net migration into the Crimea, which increased from 32,600 in 1989 to 42,800 in 1990, 43,300 in 1991 and 44,300 in 1992, declining to 20,100 in 1993. Both rural and urban population increased in the Crimea each year. The former grew from 744,700 in 1989 to 840,500 in 1994; the latter from 1,713,900 in 1989 to 1,811,200 in 1994. After 1994, as their negative natural increase intensified, exceeding the positive net migration into the Crimea, both rural and urban population began to decline. By the beginning of 2014 rural population declined to 757,600 and urban population to 1,595,600. Urbanization peaked in 1989, at 69.8 percent. The Russian invasion in 2014 disrupted the economy, shifting some people from urban to rural settings. It also induced an exodus of some Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars, but subsequent Russian military influx brought more Russians into the Crimea and especially to the city of Sevastopol.

The population is not evenly distributed: the foothills and the Crimean southern shore are populated most densely, while the Crimean Mountains and steppes are sparsely populated. There are four cities with populations exceeding 100,000: Sevastopol, Simferopol, Kerch (by 1939) and Yevpatoriia (since 1983). Of the remaining twelve cities, two (Teodosiia and Yalta) have 50,000 to 100,000 inhabitants. Almost three-quarters of the urban population lives in towns and cities situated on two important physiographic lines: the southern coast and the steppe-mountain borderline. Kerch is a distinct region of urban concentration.

Cities of the Crimea grew until 1993, and then began to decline. Sevastopol reached 375,000 in 1993, then receded to 374,000 in 1994, to 345,000 in 2014, but grew to 479,400 by 2021; Simferopol—358,000 and then 356,000, 338,000, and 336,200 in 2021; Kerch—183,000 and then 182,000 and 145,000, but grew to 152,000 in 2021; Yevpatoriia—115,000 and then 115,000 and 107,000, but increased to 108,000 in 2021; Yalta—90,000 and then 89,000, 78,000, and remained at 78,000; and Teodosiia—87,000 and then 87,000, 69,000, and 68,000. The reversal in the growth of cities was indicative of economic decline; their renewed recent growth, of Russian military build-up.

The ethnic composition of the Crimea was quite varied until 1940. The population, according to the 1897, 1926, and 1939 censuses, is shown in table 2.

The number of Crimean Tatars declined over time, often in absolute but always in relative terms: in 1770 there were estimated to be 400,000 Crimean Tatars, constituting about 90 percent of the population; by 1795 their number dropped to 137,000, or 87.6 percent; in 1897 there were 194,300 or 35.6 percent; in 1926 there were 179,000 or 25.1 percent; in 1939 there were 218,500 or 19.4 percent. In 1926 the Crimean Tatars lived mostly in the villages and constituted a majority only in the south (42.4 percent). The Germans lived mostly in the villages of the Crimean steppe (90 percent). The Bulgarians inhabited the southeast and Bilohirsk raion. The Greeks and Armenians lived in the towns of the south. The Jews (Ashkenazim, Yiddish-speaking), the Krymchaks (Tatar-speaking Jews of the former Byzantine Crimea, about 6,500 in 1939), and Karaites (a sect of Tatar-speaking Jews who rejected the Jewish law of the Talmud, about 4,500 in 1926 and 3,400 in 1937) resided in towns, the first mostly in Simferopol, the second in Bilohirsk, and the third in Yevpatoriia. Later the number of Jews increased greatly, because in 1927 the Soviet authorities began to settle them in the steppe areas. In 1936 the number of new Jewish settlers there reached 24,000, and a Jewish national raion—Larindorf—was established. Ukrainians and Russians constituted together 379,000 or 53 percent of the population. But official statistics do not provide reliable figures for the number of each nationality, inasmuch as in 1897 the Ukrainians and Russians were identified by the language they spoke. Based on the 1897 data for the Crimea, which indicated twice as many people born in the Ukrainian provinces than those speaking Ukrainian, there were most likely 180,000–200,000 Ukrainians (mostly in northern Crimea) and 180,000–200,000 Russians (mostly in the towns).

The Second World War completely altered the ethnic composition of the population. There was also a general decline in the population. Many Germans and a part of the Greeks had emigrated before the war. The Nazis eradicated most of the Jews, and the Soviet authorities deported the Crimean Tatars in 1944. After the war a large influx of Ukrainians and Russians ensued. In 1956 the Crimea’s population reached its prewar level. By 1959 almost two-thirds of the population (65.3 percent) was urban.

The ethnic composition of the Crimea according to the 1959 and 1970 census is shown in table 3.

From 1959 to 1970 the number of Ukrainians and Belarusians in the population of the Crimea increased by 80 and 83 percent, others by 100 percent, but the Russians only by 41 percent, while the number of Jews declined. The share of Russians in the population of Crimea thus began to decline. This trend continued into 1979 and 1989 (table 4).

In 1970, 49 percent of the Ukrainians in the Crimea were urban and 51 percent, rural; 68.5 percent of the Russians were urban and 31.5 percent, rural. The urban Ukrainians constituted 21.1 percent of the population, while the rural Ukrainians constituted 36.7 percent (Russians constituted 72.9 and 57.7 percent respectively).

Linguistic Russification of Ukrainians accelerated. In 1970, of 401,724 people who indicated they were fluent in Ukrainian (22.2 percent of Crimean population), 284,977 (70.9 percent of those fluent in Ukrainian) considered the Ukrainian language their mother tongue; 198,662 (41.3 percent) of all Ukrainians in the Crimea indicated Russian as their mother tongue. By 1979, of 436,797 people who indicated they were fluent in Ukrainian (20.5 percent of Crimean population), only 290,743 (66.6 percent) considered Ukrainian their mother tongue; 258,873 (47.3 percent) of all Ukrainians in the Crimea indicated Russian as their mother tongue.

The ethnic composition of the Crimea began to change in the late 1980s and accelerated during Ukraine’s independence after 1991 (table 5).

A special USSR commission (February 1988) sanctioned the Crimean Tatars (who had been deported to Central Asia in 1944) to return to the Crimea. Already the January 1989 census registered 38,365 Crimean Tatars in the Crimea, or 1.6 percent of its population. Following Ukraine’s independence, the Ukrainian government supported their return; although few resources could be provided, a movement of up to 50,000 returnees per year resulted. By January 1994 their estimated number had increased to about 250,000, or 10 percent of the population of the Crimea.

The 2001 census revealed some changes in the nationality numbers in the Crimea: the influx of Crimean Tatars (245,291, an increase of 6.3 times since 1989) and those simply identified as Tatars (13,602, or 116 percent of 1989). Returning to their former places, the Crimean Tatars settled mostly in or around Bakhchysarai and Bilohirsk (formerly in Tatar Qarasubazar). Also returning from deportation were some Armenians, Bulgarians, Greeks, and Germans. Arriving from conflict areas were the Uzbeks (2,947, or 4.6 times their number in 1989), the Armenians (10,088 or 3.6 times their number in 1989) and Azeris (4,377, or 170 percent of their number in 1989). By contrast, there was a significant decrease by 2001 in the number of Belarusians (35,157, or 69 percent), Jews (5,531 or 30 percent in 1989), and Moldavians (6,265, or 69 percent), mainly resulting from emigration. Although the numbers of Russians and Ukrainians decreased in the Crimea due to negative natural increase (deaths exceeding births), the number of Ukrainians actually increased in the Sevastopol district (from 81,756 to 84,420, or from 20.7 to 22.4 percent of the district’s population) where, after independence, the Ukrainian navy (based alongside the Russian Black Sea Fleet) drew more ethnic Ukrainians from other parts of Ukraine. Of the three major nationalities in the Crimea, the returning Crimean Tatars, constrained by lack of access to housing in cities, were least urbanized: in 1989, 23.4 percent were urban while 76.6 percent rural; by 2001 33.3 percent were urban and 66.7 percent rural. Ukrainians were more urbanized: 59.7 percent in 1989 and 62.7 in 2001. Russians were most urbanized: 74.4 percent in 1989 and 75.0 percent in 2001. Of the urban population in the Crimea in 2001, Russians comprised 67.4 percent, Ukrainians 22.4 percent, and Crimean Tatars 5.1 percent; by contrast, of the rural population, Russians made up 46.1 percent, Ukrainians 27.4 percent and Crimean Tatars 20.8 percent.

Of all the regions of Ukraine, only the Crimea had an ethnic Russian majority (60.4 percent in 2001). Since Ukraine’s independence, however, the number of Ukrainian speakers increased. Thus by 2001, 652,629 people (27.2 percent of Crimean population, up from 20.5 percent in 1979) indicated they were fluent in Ukrainian. Of that number, 284,977 (70.9 percent, up from 66.6 percent in 1979) considered the Ukrainian language their mother tongue. Meanwhile, 198,662 (41.3 percent, down from 47.3 percent in 1979) of all Ukrainian speakers in the Crimea indicated Russian as their mother tongue.

The lingua franca of the Crimea remained Russian and the Russian or Ukrainian identity often blurred into Soviet or regional Crimean identity. Of all the residents of the Crimea in 2001, 78.8 percent indicated Russian as their mother tongue. Among the self-identified Ukrainians (many born in the Crimea) only 38.8 percent indicated Ukrainian but 61.1 percent chose Russian as their mother tongue. By contrast, of the Crimean Tatars, most of whom returned from exile in Uzbekistan and were mostly Russian-speaking, 93.3 percent identified Crimean Tatar and only 6.0 percent chose Russian as their mother tongue.

After Russian annexation of the Crimea, a special population census was taken in October 2014. It recorded 2,293,693 persons present in the Crimea (the Crimean Federal District), of whom 2,284,769 (99.6 percent of those counted as present) were deemed permanent residents, a decrease from 2,342,411 permanent residents as of January 1, 2014. Since the projected natural decrease over the 10 months in 2014 was about 3,200 people, the net out-migration of permanent residents from the Crimea would be about 54,000. The number of displaced persons from the Crimea is not known, according to Charron, for they did not have to register in Ukraine, but estimates place them up to 100,000.

Russian citizenship was prioritized for quick attainment. Thus by October, of the permanent residents in the Crimea who responded to the citizenship question (2,220,113, or 97.17 percent of the permanent population), an overwhelming majority identified their citizenship as Russian—2,164,890 (97.5 percent of the respondents)—which included 5,783 (0.26 percent) retaining dual citizenship. Only 51,823 (2.33 percent) remained non-Russian citizens, of whom 46,405 (2.09 percent) were citizens of Ukraine and 1,035 (0.05 percent) of Uzbekistan; 3,400 (0.15 percent) remained without citizenship.

Regarding place of birth, in 2014 more respondents (1,247,200 or 56.3 percent) were native Crimeans than in 2001 (1,183,800 or 50.6 percent). Of those born elsewhere, 340,100 (15.4 percent) were born in the Russian Federation, a decline from 481,300 (20.6 percent) in 2001; 356,000 (16.1 percent) were born in Ukraine beyond the Crimea (in 2001 it was 383,900 [16.4 percent]); 162,600 (7.3 percent) were born in Uzbekistan (in 2001 it was 168,200 [7.2 percent]); 88,100 (4.0 percent) were born in the remaining countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) (in 2001 it was 111,000 [4.7 percent]); and 13,700 (0.9 percent) were born beyond the CIS (in 2001 it was only 12,700 [0.5 percent]). Thus between 2001 and 2014, those born in Ukraine beyond the Crimea remained almost unchanged, while those born in the Russian Federation, (and to a lesser extent in other CIS countries) were replaced by their children born in the Crimea.

Ethnic identification is more contentious. Given the political change, during the 2014 census, 5 percent of the respondents refused to identify their ethnicity. Others may have chosen a different identity. The significant changes observed in the ethnic composition from 2001 to 2014 (table 6), need careful scrutiny.

Census results suggest that on the peninsula the number of Ukrainians decreased by 232.2 thousand (40 percent) and the number of Russians increased by 41.7 thousand (3 percent). Given the negative natural increase in the population between 2001 and 2014, not all of the decrease in Ukrainians was due to out-migration. While some may have chosen not to answer the ethnicity question in 2014, others (probably children of mixed marriages) may have chosen to identify themselves as Russian. Conversely, not all of the gain in ethnic Russians reflects an in-migration of Russian military personnel, for they were not yet permanent residents; some may reflect a switch in self-reporting from Ukrainian to Russian. Moreover, the increase of Tatars cannot represent only the in-migration of pro-Russian Tatars from the Russian Federation; political persecution of activist Crimean Tatars could have induced some to shift from the suspect Crimean Tatar to the neutral Tatar identity.

Economy. The Crimea is an important maritime region of Ukraine based on its natural and human resources for agriculture, fisheries, industry, recreation and transportation. With a territory occupying 4.5 percent and a population 5.0 percent of Ukraine’s total, its share of Ukraine’s gross national product in the 2004–13 period ranged between 3.6 and 3.9 percent (of which the Autonomous Republic of Crimea accounted for 2.9 to 3.1 percent and Sevastopol 0.7 to 0.8 percent). The branches of the Crimea’s economy that stood out above average as percent of Ukraine’s total in 2008, for example, were fishing (47.8 of all fishing in Ukraine), hotels and restaurants (12.3), health care (8.0), state administration (6.3), construction (5.9) and social services (5.2). All branches of economy are represented in the Crimea as they do in Ukraine as a whole, but their profiles, expressed as shares in their gross regional product, vary. Comparing the profiles of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, the district of Sevastopol, and Ukraine as a whole (for comparison, in brackets), each of their branches contributed to their gross regional products in 2008 as follows: agriculture and forestry, 9.7, 0.1, (7.6); fisheries, 0.4, 0.0, (0.0); mining, 2.1, 1.9, (6.3); manufacturing, 12.3, 11.9, (19.1); energy production and distribution, 3.2, 4.2, (3.4); construction, 5.6, 4.6, (3.4); trade and repair, 13.6, 19.7, (15.3); hotels and restaurants, 4.4, 1.2, (1.1); transport and communications, 10.1, 11.7, ( 10.1); finance, 3.4, 8.2, (8.0); real estate and infrastructure services, 9.5, 12.4, (9.9); government administration and research, 8.2, 11.5, (5.2); education, 6.1, 6.8, (5.1); health care, 8.3, 3.3, (3.4); social services, 3.1, 2.5, (2.1).

Crimea’s economy evolved over time. Before Russia annexed the Crimea in 1783, the Tatars led a seminomadic existence on the steppes, engaging in herding and extensive farming, and, in the southern Crimea, in orcharding, vegetable farming, and cottage industries. Under Russian rule the economy of the Crimea at first declined because of the emigration of Tatars and Greeks; later it improved owing to the colonization of the steppes, the development of viticulture and tobacco growing in the south, and the eventual completion of a railroad to Sevastopol. In the northern Crimea the steppes were put to the plow, and grain growing replaced animal husbandry. The proximity of good harbors facilitated grain export. In the south the intensive cultivation of crops that were in high demand in central Russia and the health resort industry rapidly gained in importance. (At the beginning of the 1910s almost 150,000 tourists per year visited the Crimea.) Various branches of the food industry and salt industry, shipbuilding at Sevastopol, and later iron-ore mining in Kerch (see Kerch Iron-ore Basin) accounted for most of the industrial production. During the Soviet period industry has expanded rapidly: while in 1913 it accounted for 45 percent of the region’s production, by 1940 it had reached 80 percent. From the 1950s, within the Ukrainian SSR, intensive farming expanded greatly, as did the number of health and tourist resorts. After 1991, in independent Ukraine, the economic crisis and privatization affected some sectors of manufacturing and agriculture but increased the importance of services and scientific research. In 2013, after the city of Kyiv (5.2 percent) and Odesa oblast (5.3 percent) the Crimea had the lowest unemployment rate (5.7 percent) in the country (Ukraine’s average was 7.2 percent). The illegal Russian occupation of the Crimea in 2014 impacted its economy, notably irrigation agriculture and tourism.

Science and education. About 100 scientific institutions conducted fundamental research in the Crimea in 2013. Of that number some 20 were branches of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. The outstanding ones included: 1) the Crimean Astrophysical Observatory (since 1950s at Naukove in the Crimean Mountains, 13 km ESE of Bakhchysarai, with the largest reflector in Europe [1960]; the old, smaller reflector at Simeiz [est. 1908 by Nikolai Maltsov at Mount Koshka]) was supplemented by the RT-70 (70 meter radio telescope) of the Crimean Laser Observatory, the largest one of two in the world (at Katsiveli near Simeiz); 2) the Marine Hydrophysical Institute of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine (at Sevastopol, established as the Black Sea Hydrophysical Station in 1929, becoming host of the Marine Hydrophysical Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR in 1963, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine since 1991); 3) the Institute of the Biology of Southern Seas of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine (established in 1963 in Sevastopol, with its branch in Odesa, based on the Odesa Biological Station [est. 1953] of the Institute of Hydrobiology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine]); 4) the Mineral Resources Institute and 5) the Crimean branch of the Institute of Archeology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. The National Academy of Agrarian Sciences of Ukraine had its affiliates, 1) the Institute of Agriculture of Crimea (at Simferopol), 2) the National Institute of Grape Growing and Wine-making ‘Maharach’ (established on the basis of a wine-making school at the Nikita Bitanical Garden in 1928, research center on wine-making for the USSR Ministry of Food Industry, 1940–91); and 3) the Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food of Ukraine, the Ukrainian State Institute for Orchards and Vineyards (in Simferopol). Since the Russian occupation (2014), most of these scientific research institutes became part of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Postsecondary education in the Soviet period emphasized technical skills; in the post-Soviet period the universities expanded. Postsecondary vocational-technical schools in the Crimea, initially well represented, declined from 29 in 1990–91 to 27 in 2005–6 and 20 in 2013–14, with their student enrolment (in thousands) declining, respectively, from 25.0 to 14.1 and 9.4. By contrast, there were 4 universities in the Crimea in 1990–91, increasing to 18 in 2005–6 and then adjusting to 16 in 2013–14; their student enrolment (in thousands) grew from 22.7 to 63.2 and then dipped to 50.4, respectively.

The universities are located in Simferopol, Sevastopol and Kerch. The oldest is the Tavriia National University (established in 1918 as Tavriia University; it drew on some faculty from Kyiv, including the Academician Volodymyr Vernadsky, who served as its rector in 1920; re-named the Frunze Crimean University in 1921; in 1925 it was re-named the Frunze Crimean State Pedagogical Institute, then in 1972 the Frunze Simferopol State University; in the Soviet period it spawned the agricultural institute [1922], the pedagogical institute [1925], and the medical institute [1931]; during Ukraine’s independence, the institutes were named universities [eg. the Crimean State Agrarian University in 1997, re-named the Crimean Agro-technological University in 2003; the Crimean State Medical University named after S. Hordiievsky, in 1998]; in 1999, the institution was granted a national university status, was named in honor of Volodymyr Vernadsky, and assumed its present name; in 2014, under Russian occupation, these and its other branch campuses were merged into one, and the institution re-branded the V.I. Vernadsky Crimean Federal University, its Faculty of Ukrainian Philology closed and the departments of ‘Ukrainian Linguistics,’ ‘Culture of the Ukrainian Language’ and ‘Theory and History of Ukrainian Literature’ amalgamated into the ‘Faculty of Slavic Philology and Journalism’; meanwhile, its pro-Ukrainian faculty and administration relocated to Kyiv, retaining its historic name, with new student intake in 2016). The other two important state universities are the Sevastopol State University (est. 1951) and 3) the Kerch State Marine Technology University (est. 1992). Other smaller universities include the Crimean Engineering Pedagogical University (est. Simferopol, 1993, as the Crimean State Industrial Pedagogical Institute by the Crimean Tatars, acquired present title and status in 2003).

Industry. Food production is the Crimea’s main industry, accounting for 44 percent of industrial production in the 1960s, 37 percent in 1990, and 30 percent in 2000. It is followed by machine building and metal-working (32 percent in 1990 and 27 percent in 2000). Iron-ore mining and ferrous metallurgy, based on now depleted deposits of the Kerch Iron-ore Basin, declined to 2.6 percent by 2000, while the chemical and petrochemical industries, fed by new and developing offshore hydrocarbon deposits, increased from 6.9 percent in 1990 to 20.1 percent in 2000. Less important were the stagnant building-materials industry (4.9 percent in 1990, 3.2 percent in 2000), and the drastically declining light industry (6.8 percent in 1990, 0.9 percent in 2000).

The oldest and the basic industry of the Crimea, the food industry, processes locally grown produce. Winemaking was particularly important in the 1960s, accounting for over 20 percent of the Crimea’s production. In 1968, 362 million liters of vinous material were produced. Dessert wines made by the firms of Masandra and Zolota Balka, which are located near Yalta, Alushta, Sevastopol, Sudak, and other cities, were sold throughout the former USSR and the world. Grape juice was produced by plants in Sevastopol and Teodosiia. The fish-processing industry (13 percent of the Crimea’s industry in the 1960s) was highly developed in Kerch, with smaller operations in Sevastopol, Yalta, and Yevpatoriia. Fruit and vegetable canneries remain located in Simferopol, with smaller plants in Bakhchysarai, Dzhankoi, and Sevastopol. Tobacco is cured in Simferopol and Yalta and processed in Teodosiia. The essential-oils industry, concentrated in Simferopol, Bakhchysarai, Alushta, Sudak, and Nyzhnohirskyi, produced in the 1960s close to 40 percent of the former USSR’s rose oil and 50 percent of its lavender oil. Local consumer-oriented products included grain-milling (Krasnoperekopsk, Simferopol), bread products (Simferopol, Sevastopol, Bakhchysarai), milk products (Dzhankoi, Simferopol, Sevastopol, and Yevpatoriia) mineral waters (Armiansk, Saki), and beer (Simferopol).

Heavy metallurgy was based on the rich deposits of the Kerch Iron-ore Basin. The Komysh-Buruny Iron-ore Complex (established in the 1930s) extracted local iron ore and shipped it to the metallurgical plants of the Donets Basin and the Dnipro Industrial Region. In return, coking coal was shipped from the Donets Basin to smelt iron and steel in Kerch; this smelter was not rebuilt after the Second World War. Metalworking industries still operating include: aluminium and ferro-alloys in Sevastopol, powder metallurgy, stamping and pressing in Simferopol and metal coating in Yevpatoriia. The machine-building industries produce equipment for the food industry (Simferopol), tractor attachments (Dzhankoi), farming-machinery parts (Simferopol), electronic equipment, and parts for making and repairing ships (Kerch and Sevastopol).

The chemical industry is based on the various large salt reserves of the Syvash Lake and other saline lakes. Chemical-bromate plants are found in Armiansk and Krasnoperekopsk on the Perekop Isthmus and at Saky. Plastics and consumer-chemicals plants are located in Simferopol and Sevastopol, with smaller plants in Alushta, Kerch and Yevpatoriia. The construction-materials industry is based on abundant local resources; it produces reinforced-steel products, cement, and bricks.

The energy to run industry is provided by the regional thermoelectric stations (DRES) near Simferopol, Sevastopol, and Kerch. Work began on the Aktash Nuclear Power Station on the Kerch Peninsula in 1977, but because its site was prone to earthquakes and post-Chornobyl nuclear disaster concerns, it was abandoned in 1990. In the 1960s natural gas began to be tapped in the western and northern Crimea (where there are resources of 14 billion cu m) and gas pipelines running from Hlibivka and Dzhankoi through Simferopol to Sevastopol have been laid. Exploration offshore in the 1970s and 1980s discovered natural gas resources estimated between 4 and 13 trillion cu m, up to one-third of Ukraine’s resources. Three offshore gas fields (Holitsynske, Arkhanhelske, and Shtormove) were brought into production (in 1975, 1992 and 1993, respectively) with the hope of making Ukraine self-sufficient in natural gas, but were seized by the Russian Federation in 2014.

Agriculture. With 4.3 percent of Ukraine’s farmland, 3.7 percent of Ukraine’s cultivated land and 3.2 percent of Ukraine’s population employed in farming (1996), the Crimea contributed, between 1990 and 2009, from 3.2 to 4.5 percent of Ukraine’s agricultural production, including 2.3 to 4.9 percent of crop production and 3.5 to 5.5 percent of animal products. As in all of Ukraine, since 1991 the animal husbandry component declined in favor of the more lucrative crops for export.

After 1991, collective farms and state farms were replaced by commercial family farms, farming associations and corporate farms, based mainly on renting farmland. Whereas in 1985 there were 119 collective farms and 155 state farms in the oblast, they were replaced by 2009 with 2,211 agricultural enterprises of different types: 1,561 commercial family farms, 305 farm corporations, 163 private farm enterprises, 89 farm co-operatives, 31 state farms and 62 other farming enterprises. Rural households, however, continued to practice subsistence gardening and subsidiary animal husbandry.

Within the Crimea, there are three agricultural regions: the steppe region with its grain growing and animal husbandry; the Crimean southern shore and foothills with their fruit growing, grape growing, and tobacco farming; and the mountains with their forests and summer pastures.

Arable land covers 56.2 percent of the Crimea’s area. Pastures, hayfields, and grazing land cover 23.4 percent; forests and brush cover 16 percent; and vineyards and orchards cover 7.9 percent. The total area under cultivation grew from 804,000 ha in 1913 to 1,144,000 ha in 1959, 1,177,000 ha in 1978, 1,215,100 ha in 1990, peaked at 1,233,000 ha in 1995, then declined to 1,165,200 ha in 2000 and rose slightly to 1,199.8 ha in 2013. Of this area in 2013 some 528,300 ha were devoted to grains (548,400 ha in 1990, 540,100 ha in 1978, 650,000 ha in 1959 and 700,000 ha in 1913); 146,500 ha to industrial crops (93,300 ha in 1978); 40,400 ha to vegetables and melons (41,100 ha in 1978, 39,000 ha in 1959 and 12,000 ha in 1913); and 40,000 ha to fodder crops (504,100 ha in 1978, 62,000 ha in 1959 and 19,000 ha in 1913).