Donetsk

Donetsk [Донецьк; Donec'k]. Map: VI-18, DB Map: DBIV-3. City (2020 pop 908,500), called Yuzivka until 1924, then Staline or Stalino until 1961. Donetsk was the administrative center of Donetsk oblast until April 2014, when it was captured by the Russia-supported separatists to become the capital of their self-proclaimed ‘Donetsk People’s Republic’ (DPR). Located on the upper reaches of the Kalmiius River in the steppe region, this industrial settlement (city since 1920) grew to become the largest center of coal mining and metallurgy and the fifth-largest city in Ukraine. Donetsk, a focus of railways and highways, was severed in 2014 from the rest of Ukraine by war with an active front to the north and west of the city. It also had a modern airport on its northeastern outskirts, destroyed in a fierce 242-day battle (September 2014 to January 2015) for its control. Donetsk comprises 9 administrative sections (city raions). The Greater Donetsk, called the Donetsk Council (January 2020 pop 924,200), extends to the southeast to include the city of Mospyne, the towns of Horbachevo-Mykhailivka and Laryne, and several villages. Together with the adjacent cities of Makiivka (378,700), Yasynuvata (34,400), Khartsyzk (100,000) (all three controlled by the DPR) to the east, and Avdiivka (32,400, controlled by the government of Ukraine) to the north, Donetsk forms an urban cluster of 1,250 sq km and a population of about 1.5 million, surpassing Kharkiv and thus representing the second-largest metropolis in Ukraine.

History. Donetsk was established in 1869 as a settlement for the workers of the New Russia Company of Anthracite, Iron, and Rail Production (known today as the Donetsk Metallurgical Plant), owned by the Welsh industrialist John Hughes and named Yuzivka (in Russian, Yuzovka) after him. It was located 5 km south of the village of Oleksandrivka (est 1779) and its first mechanized coal mine in the Russian Empire (est 1841). Rapid industrial growth was promoted by the availability of large anthracite-coal deposits (especially coking coal) and water and by the construction of the extension from Kostiantynivka (1872) and then the Donbas–Kryvyi Rih (1883) railway line. In 1876 its metallurgical plant was the largest in the Russian Empire. In 1889 a French- and German-owned machine-building plant was constructed, which is now known as the Donetsk Machine-Building Plant. It produced equipment for mines (nine by 1899) owned by English, French, Russian, and Ukrainian industrialists.

As industry developed, the population increased greatly. The overwhelming majority of the newcomers were migrant Russian workers, as the Ukrainians in the surrounding areas were unwilling to abandon their agricultural pursuits in favor of a grimy urban, industrial lifestyle. Yuzivka had a population of 5,500 in 1884; 32,000 in 1897; and 70,000 in 1913, of which 43,000 were workers and their families. While the management and engineers enjoyed a well-built district called the ‘English colony’ north of the factory, enhanced with an English school and the Great Britain Hotel, and the Russian civil servants, merchants and craftsmen had their quarter, the ‘New World’ (‘Novyi Svet’), next to Oleksandrivka and anchored on the Cathedral of Transfiguration of Jesus (built, 1883–86; demolished, 1931; re-built, 1997–2006), most of the workers lived in poor one-story dwellings scattered chaotically along the banks of the Kalmiius River. Merciless exploitation and difficult living conditions led to massive strikes by the workers in 1875, 1887, 1892, 1898, 1905, and 1913 (3,500 miners). By 1914 Yuzivka had 4 factories, ten mines, many small enterprises and 50,000 residents. Since most of Yuzivka’s population was Russian, the Ukrainian national movement had no apparent influence there. In the 1900s, besides the Russian revolutionary press, some Ukrainian publications reached Yuzivka. Workers’ groups of the Prosvita society were active. In 1917–18 the Mensheviks were the dominant political party in Yuzivka.

In April 1918 Yuzivka was occupied by German-Austrian forces, and in November by the army of General Anton Denikin. Then it changed hands several times before it was taken by the Red Army in January 1920. During the First World War, the Revolution of 1917, and the Ukrainian-Soviet War, 1917–21, the city declined, and its population greatly decreased (32,000 in 1923). Gradually it was rebuilt. In 1925 Donetsk (then known as Staline or Stalino) became an okruha center and in 1932 an oblast center. During the period of Joseph Stalin’s five-year plans the city experienced its highest rate of development. At the end of the 1930s there were 223 large enterprises in Staline. It produced 7 percent of Ukraine’s coal, 5 percent of its steel, and 11 percent of its coke. New plants were set up: a motor-vehicle repair plant, a mechanical plant (Donenerho), and a nonferrous-metalworking plant. Ten new mine shafts were opened, among them NN29, 17–17-bis, and the Red Star. Staline became a cultural center with 2 theaters, 4 institutions of higher education, 113 schools of general education, and 9 tekhnikums. The writers’ association Zaboi was active here, and a publishing house was established. In 1941 an opera and ballet theater was opened (see Donetsk Opera and Ballet Theater). As industry developed, the population increased. In 1926 Staline had 105,900 inhabitants (26.1 percent Ukrainians, 56.2 percent Russians, 10.7 percent Jews). Its population, in part refugees from the Famine-Genocide of 1932–3 as well as the influx of workers mainly from the Russian SFSR and Belorussian SSR, grew to 287,000 in 1933 and 472,400 in 1939.

During the Second World War Staline was under German occupation from 1941 to 1943. The destruction sustained by the city was estimated at four billion rubles. The population fell to 175,000. Industrial reconstruction lasted until 1950. Along with the reconstruction and renovation of existing enterprises and mines, there was considerable growth in the machine building, chemical industry, light industry, and food industry. The city’s growing need for water was met with the building of the Donets-Donbas Canal (1954–58) and the Dnipro-Donbas Canal (1969–81), which brought water from the Dnipro River to supplement the Donets River water south of Izium. The city’s infrastructure and housing was also expanded. By 1959 Staline’s population had reached 708,000 (31 percent Ukrainians, 51 percent Russians, 3 percent Jews). The city’s rate of population increase then slowed down because of a change in economic policy aimed at reducing the use of coal as fuel and the re-orientation of Soviet government investment to Siberia for oil and gas extraction and hydroelectric power development. In 1971 Donetsk’s population was 891,000, in 1979 it was 1,021,000, in 1989 it was 1,113,000 (41 percent Ukrainians, 52 percent Russians, 1.6 percent Jews) and reached 1,121,000 in 1991.

Following Ukraine’s independence (1991), Donetsk’s population stopped growing and from 1993 declined to 1,024,700 by 2001, largely as a result of the economic difficulties experienced by the city’s aging smoke-stack industries combined with its ageing population. Even so, the politicians from Donetsk, like Viktor Yanukovych, and oligarchs, like Rinat Akhmetov, ensured a more than equal share of government support for the city and its industries. The ethnic composition changed to a rising share of Ukrainians and a decreasing share of Russians and others (46.7 percent Ukrainians, 48.2 percent Russians, 0.5 percent Jews) but, among the Ukrainians, an increasing share of native Russian speakers. Schooling in the Ukrainian language, having been curtailed by the Soviet government in Donetsk in the 1960s, revived, but its promotion was resented by many Russian speakers. Population continued to decline to 950,000 in 2014.

On 7 April 2014, after President Viktor Yanukovych had fled Ukraine to seek asylum in the Russian Federation and the Russian military had seized the Crimea, pro-Russian separatists took control of Donetsk Oblast State Administration and declared the ‘Donetsk People’s Republic’ (DPR), asking for Russian intervention. The hostilities, with Russian support of the separatists, resulted in the entrenchment of the DPR with its capital in Donetsk.

Economy. Donetsk was one of the largest metallurgical, coal-mining, machine-building, and chemical-industry centers in Ukraine. In 2008 it had about 200 industrial enterprises which employed about 190,000 workers. The value of the city’s industrial production in 2008 was distributed by sectors as follows: energy and water supply (26.3 percent), metallurgy (29.4 percent), food processing (13.9 percent), machine building (12.1 percent), and coal mining and processing (9.1 percent). The coal industry in Donetsk had 4 enrichment plants and 21 mineshafts in 2008, of which 17 were state-owned as part of Donetskvuhillia (established in 1996) and the remaining 4 privatized. The latter included the newest (opened in 1958) and deepest (1,270 m), the O. Zasiadko shaft, which had several recent methane explosion disasters (1999, 2001, 2002, 2006, 2007, and 2015). Deprived of their markets since 2014, most of the coal mines are now closed.

Metallurgy, the leading industry in Donetsk, was based on local coking coal (later supplemented with natural gas from Stavropol and Orenburg), iron ore from the Kryvyi Rih Iron-ore Basin and manganese from the Nikopol Magnanese Basin. These raw materials supported the giant Donetsk Metallurgical Plant (founded in 1869, expanded in 1904, 1910, and 1912, then rebuilt and modernized after both world wars, producing nearly 9 percent of the steel in Ukraine in 2010); the Donetsk Rolled Steel Plant (established in 1956, expanded to make water supply and drain pipes in 1962, stainless steel ware in 1974, privatized in 1993, and upgraded in 2011); and the Donetsk Electrometallurgical Plant (established in 1997, using clean energy to produce rectangular and round specialty high quality rolled steel). The Donetsk non-ferrous metallurgy plant produced aluminum, copper and brass from scrap and imported materials. Since 2014 their markets and output declined.

The machine-building industry in Donetsk consisted of 25 large plants, each specializing in its production: the mining machines plant (est 1889), miner rescue equipment, respirators, energy generating equipment, coke chemical plant equipment, metal construction equipment, stamping and press-forming, cables, food-industry equipment, auto-repair, and refrigerators. The radio-electronics Topaz plant (est 1987) made the Kolchuga mobile radar targeting system for missile launching; in 2014 its production equipment was seized and removed to Russia; the Ukrainian potential to produce the Kolchuga was transferred to the Iskra plant in Zaporizhia.

Of the eight chemical plants, the largest included the Donetsk and Rutchenkove coke-chemical plants, two plastics plants, the Khimik and the Donetsk chemical reagents plants (the latter seized by separatists, gutted and its equipment sold for scrap in 2014), insulators plant, and mineral fibers plant. The Donetsk State Chemical Plant used to make and pack explosives into artillery shells, land mines and missile warheads; in 2002 it switched, under a US NATO-sponsored program, to dismantle the armaments in storage and make toys instead.

The building industry was well developed. A dozen plants produced asphalt and fabricating reinforced cement building materials, stone fabrication and insulation materials for buildings, canals and mines. Light industry enterprises produced cotton cloth, yarn, hosiery, knitted materials, clothing, and shoes; since 1991 they have suffered from import competition and some closed. The food-industry plants continue to produce beer, liqueurs, liquor, dairy products, meat, and fish, but the curtailed access to raw material suppliers since 2014 has complicated their operations.

Industrial production and commerce, already in decline in Donetsk by 1991, were revived with privatization and some foreign direct investment. Donetsk benefitted from the growth of the service sector. The 2014 conflict, however, ruined the economy. Infrastructure was damaged, supply chains were disrupted, and the production of the city’s major enterprises that used to export their products widely declined or stopped.

Culture. Until 2014 Donetsk was one of the largest centers of learning and culture in Ukraine, containing about 30 research and development institutions. In 2014 the pro-Ukraine personnel relocated to safety, establishing alternate places of work. Of the institutes of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine that were located in Donetsk, only the Institute of Applied Mathematics and Mechanics of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine remained within Donetsk oblast, moving to the Ukraine-controlled Sloviansk. The other four, the Institute of the Economics of Industry of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, the Donetsk O. Halkin Physical-Technical Institute of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, the L. Lytvynenko Institute of Physical-Organic Chemistry and Coal Chemistry of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, and the Institute of Artificial Intelligence of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, relocated to Kyiv. There were 14 other research institutes in Donetsk not affiliated with the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, among them of Ferrous Metallurgy (est 1960), of Geological-Ecological Problems of the Donbas, of Medical-Ecological Problems of the Donbas, of Mining Mechanics, of Technical Cybernetics, of Mining Lifesaving, and of Work Physiology.

There were, in 2011, nineteen institutions of higher learning, including five universities: the Donetsk National University (est as pedagogical institute, 1937; became university, 1965; awarded the national university status, 2000; named after Ukrainian poet and dissident martyr, Vasyl Stus, in 2016 after transferring to Vinnytsia in 2014, with a branch campus in Mariupol; its science labs and their researchers remained in Donetsk), the Donetsk National Technical University (est 1921, the pro-Ukrainian faculty relocated to Pokrovsk, then called Krasnoarmiisk, in Donetsk oblast), the Donetsk National Medical University (est 1930, in 2014 relocated to Kramatorsk and Kropyvnytskyi, with branch campuses in Donetsk oblast in Mariupol and Lyman), the Donetsk National University of Economics and Trade (est in Kyiv in 1920, moved to Kharkiv in 1934 and Staline in 1959; now in Kryvyi Rih, with branch campuses in Kramatorsk and Mariupol), the Donetsk State Management University (relocated to Mariupol).

Three theaters (the Donetsk Opera and Ballet Theater, established in Donetsk in 1932; the Donetsk Ukrainian Music and Drama Theater, established in Kharkiv in 1927, relocated to Staline in 1933; and the Donetsk Puppet Theater, established in Kharkiv in 1925 and transferred to Staline in 1933), the Donetsk Philharmonic Orchestra (est 1933), and the Donetsk Circus continue to provide artistic entertainment in Donetsk. There are two state museums—an oblast regional studies museum (1924) and a city art and historical museum—as well as 15 other museums, an oblast archives (1924), many libraries, and two planetaria.

The Donbas publishing house (est 1964) was located in Donetsk. Several oblast newspapers, including Vechernii Donetsk, Vesti Donbassa, and Donets’kyi kriazh, were published here. There are five local television station and a radio station. There was a branch of the Writers' Union of Ukraine, which has published the bilingual journal Donbas/Donbass since 1968 (until 1957 it published the Russian bimonthly Literaturnyi Donbass and from 1958 to 1968 the Ukrainian almanac Donbas), switching again to the Russian bimonthly Literaturnyi Donbass in 2014. Branches of the Union of Journalists of Ukraine and of the Union of Artists of Ukraine, a branch of the Ukrainian Theatrical Society, and a branch of the National All-Ukrainian Musical Association were also active in Donetsk until 2014.

Donetsk was a major sports center of Ukraine with a highly developed infrastructure. It used to host USSR-wide and international championships in numerous sports. The most popular sport in Donetsk, football (aka soccer in North America), had three stadiums: Shakhtar (Miner), Metalurh (Metallurgist), and Olimpik (Olympic), all named after their teams; the fourth, Donbas Arena, was opened in 2009 in advance of co-hosting the 2012 UEFA European Football Championship. Since 2014 the premium teams, the Shakhtar and the Olimpik, left Donetsk for other cities of Ukraine; the stadiums remain scarcely used. Hokey, the second most popular sport, had three facilities for its teams in Donetsk: Arena Druzhba (destroyed in May, 2014), Kalmiius Arena, and Tov Kalmiius Arena. Its premier team, Donbas, won the championship of Ukraine and the IIHF (European) Continental Cup in 2013. Other significant sports teams, with their facilities, included basketball (‘Donetsk’), American football (‘Skify’ ie ‘Scythians’), rugby (‘Tyhry Donbasu’ ie ‘Tigers of the Donbas’), boxing, mixed martial arts, karate, tennis, equestrian arts, gymnastic and track and field sports.

City plan. The first general plan of the city was designed by the architect Petro Holovchenko of Odesa in 1932 and re-worked in 1937 to keep up with its growth. The challenge was to build around industrial sites, slag heaps and cone-shaped piles of mine tailings 100 m high. The post-Second World War reconstruction and notably its grand buildings made the city a proletarian showcase featuring wide boulevards and large parks with Soviet grand monuments.

Greater Donetsk (aka Donetsk Council) now appears on a map like a broad-based pyramid that stretches for about 50 km from east to west and about 35 km from north to south, covering an area of 571 sq km. The city proper, with its parks and built up areas, extends from its outermost points about 33 km east to west and about 20 km north to south, covering about 400 sq km. The city is divided into nine administrative (city raion) sections, two of which extend to the southeast to incorporate the rest of Greater Donetsk.

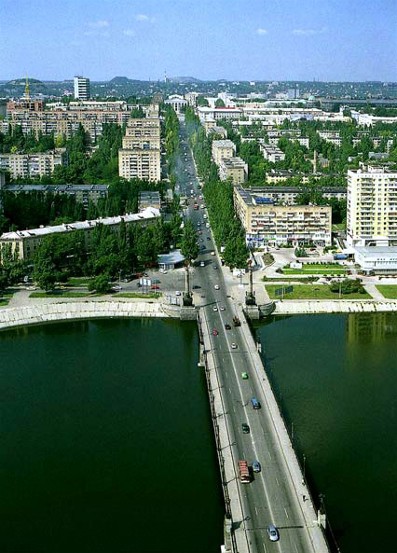

The city center is flanked by the Kalmiius Reservoir in the east and the City Reservoir in the west. Its main thoroughfare, Artem Street, runs for 8 km, from its southern terminus, the Donetsk Metallurgical Plant, north through the central Voroshylov Raion and then west through Kyiv Raion to the main Donetsk passenger railway station. Crossing it are several broad boulevards, including Illich Prospect, the Shevchenko Boulevard and the Peace Prospect. Located along the Artem Street are the main administrative, cultural and historic buildings—the Donetsk Oblast (now the DPR) Administration, the Donetsk City Hall, The Donetsk National Technical University, the Donetsk State Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre (opened 1941, and named after Anatolii Solovianenko, 1999), the Ukrainian (designated National, 2009) Musical and Drama Theater, the Donetsk Oblast Philharmonic Hall, the Olympic Stadium, the Cathedral of Transfiguration of Jesus, the historic Great Britain Hotel, the more recent Central Hotel and the 5-star Donbas Palace Hotel. Parallel to and on the west side of Artem Street are the broad Pushkin Boulevard and the University Street (where the Donetsk National University is located and, farther north, the unique Forged Figures Park). On the east side of Artem Street is the Cheliuskintsiv Street, which has the Central shopping mall and, at the Peace Prospect, next to the Olympic Stadium, the new Donbas Arena (now closed), and just north of it, the ExpoDonbas exhibition center (now serving as a Russian military base).

Donetsk is one of the greenest cities in Ukraine: in 1976 up to 12,000 ha of the city’s land were parkland and gardens, increasing to 25,900 ha by 1988; the green suburban belt had almost 72,000 ha. The outstanding parks of Donetsk are Shcherbakov Park, which is the oldest, the City Park of Culture and Recreation (formerly the Komsomol Park) which now includes the Donbas Arena, track and field facilities, tennis courts, children’s train ride, and the Musical Park overlooking the Kalmiius Reservoir) , Seredni Prudy park, Miskyi Lis park, Verkhnii Lis park, Putylivskyi Lis park, and the Donetsk Botanical Garden of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine (est 1964, awarded national status in 2001; see Botanical garden).

Donetsk is a large railway junction of 11 stations at the center of the densest railway network in Ukraine. Inter-city bus service emanated from two terminals. Their functionality has been limited since 2014 by hostilities. The basic means of transportation within Donetsk are the trolley (1927), trolleybus (1939), and bus. The building of the Donetsk Metro (subway), planned since 1976, was started in 1993, lapsed and renewed in 2012, but was abandoned in 2013 due to difficulties of financing. The suburbs and adjoining cities to the east are linked by trains.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Svitlychnyi, K.; Myronov, M. Donets'k (Kyiv 1966)

Shul'gin, N. ‘Donetsk za 50 let,’ Stroitel'stvo i arkhitektura (1967)

Donetsk: Istoriko-ekonomicheskii ocherk (Donetsk 1969)

Kobets', H.; Maksymov, O.; Chystiakov, V. ‘Donets'ku 100 rokiv,’ UIZh, 1969, no. 9

Istoriia mist i sil Ukraïns'koï RSR: Donets'ka oblast' (Kyiv 1970)

Severin, S. ‘Landshaftnaia arkhitektura Donetska,’ Stroitel'stvo i arkhitektura (1979)

Bondarenko, Ia. ‘Donetsk,’ Heohrafichna entsyklopediia Ukrainy (Kyiv 1989)

Pirko, V. ‘Naidavnishi mista Donechchyny’ ‘Skhid’ Spetsvypusk (Donetsk 2004)

Donets'k: Universal'nyi atlas (Kyiv 2011)

Ihor Stebelsky

[This article was updated in 2020.]

%20early%2020th%20century.jpg)

%20city%20school%20and%20womens%20gymnasium.jpg)