Art

Art [мистецтво; mystetstvo]. Art in Ukraine developed under the influence of different internal and external factors in different periods. As a result of historical circumstances and its geographic location between Europe and Asia, Ukraine came into contact with various foreign influences, which were either absorbed into its culture or rejected. For this reason it is important to distinguish between Ukrainian art, ie, art that is linked to the Ukrainian people in spirit and style, and art in Ukraine, ie, art that encompasses all the artistic phenomena that arose on Ukrainian territory.

In ancient times Greek art and Scythian art interacted in Ukrainian territory, producing an original style. Later, Byzantine art masters, who often settled in Ukraine and became assimilated, were the leading producers of art. During the Renaissance Italian artists immigrated to Ukraine, as did German artists during the baroque period. In the 18th–19th century numerous Polish and Russian artists worked in Ukraine. Today much of the art in Ukraine is produced by non-Ukrainians. Similarly, many Ukrainian artists of the 18th and 19th centuries contributed to Polish or Russian art and today contribute to the art of the countries to which they have immigrated. These factors must be taken into consideration in defining the nature and the boundaries of art in Ukraine.

The origins of Ukrainian art can be traced back to the Paleolithic Period. Carved mammoth tusks from this period have been uncovered in Kyiv and other localities in Ukraine. Figures of animals and birds and distorted representations of women, often decorated with curvilinear incisions, were found at the same sites. Drawings of mammoths and stags in stone caves date back to the same time. The type of meander incision found on the mammoth tusks at the Mizyn archeological site is unique in Europe and is much older than that found in China or Mexico. The development of art is even more evident in the Neolithic Period, when pottery developed particularly rapidly in Ukraine. The ceramic and terra-cotta figurines of humans and animals that belong to the Trypillia culture are ornamented with a carved or painted spiral. The Bronze Age and Iron Age in Ukraine had a greater impact on the production of ordinary implements and arms than on art. In the middle of the 1st millennium BC Scythian art established itself in Ukraine and, blending with the culture of the Greek colonies in southern Ukraine (see Ancient states on the northern Black Sea coast), produced gold jewelry whose artistry surpassed even that of Greece.

After the decline of the Roman Empire the migrating tribes (Goths, Huns, etc) that crossed Ukraine on their way from Asia to Europe left many traces of their cultures behind. The local cultures in Ukraine differed from the cultures of the migrating peoples, as is evident from discoveries such as that of the silver hoard from the 6th century AD in Martynivka near Kyiv (see Martynivka hoard).

From the 10th century Byzantine art and culture came to play an important role in Kyivan Rus’. Its influence was particularly strong in the Crimea, where many Christian churches were in existence in Chersonese Taurica by the middle of the 1st millennium AD. Prince Volodymyr the Great imported icons and builders from Chersonese to construct churches in Kyiv.

The Princely era (10th–14th century) in Ukraine was a period of intense cultural growth. During this time such monumental structures as the Church of the Tithes, the Saint Sophia Cathedral, and the Dormition Cathedral of the Kyivan Cave Monastery were erected in Kyiv. Many grand buildings, such as the Cathedral of the Transfiguration, were built in Chernihiv. Fine churches also appeared in other cities; however, only a few of them survived to modern times, and many of those that did were destroyed by the Soviet authorities. The art forms that came to Ukraine together with the Byzantine rite became localized as the apprentices of Greek masters became masters in their turn. Byzantine art had an inclination towards large, decorative, monumental forms and towards vivid colors, particularly gold. The expensive art of the mosaic became well rooted in Ukraine but remained unknown in the northern regions such as Novgorod the Great and Suzdal, which at that time were vassals of Kyiv. Other art forms also developed in Kyiv—miniature painting, jewelry and ornamentation, the mosaic, fresco painting, and the icon. Having absorbed and developed the Byzantine forms of art, Kyiv itself became an art center for Eastern Europe.

Since culture is closely related to political conditions, the culture of Kyivan Rus’ flourished only as long as Kyiv had the power to resist the invasions of the nomadic Asian hordes. Rus’ sheltered the West European countries from many of the invasions, thus making it possible for these countries to develop their arts. But at the beginning of the 13th century Kyiv’s military might and culture began to decline under the onslaught of the Golden Horde. Kyivan culture flourished for another century in the western parts of Ukraine, in the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia, but even these territories, weakened by repeated invasions, fell under Polish domination in the mid-14th century and eventually became part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In Western Ukraine only fragments of the artistic monuments from this period have been preserved, while in Poland under more favorable political conditions entire fresco ensembles painted by Ukrainian masters of the 14th–15th century have survived.

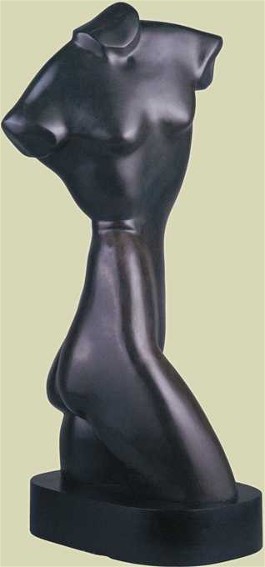

The dominance of Byzantine art in Ukraine was overcome in the 16th century by the impact of Renaissance and then baroque art. The new movements gave rise to new genres such as portraiture, although in Ukrainian art they manifested themselves more forcefully in architecture than in painting or sculpture. The baroque developed in Ukraine during the time of Cossack wars with Turkey and Poland; hence, in Ukrainian art this style is known as the Cossack baroque. The finest examples of this style were produced during the reign of Hetman Ivan Mazepa. With his defeat at the Battle of Poltava in 1709, Kyiv was replaced by Saint Petersburg as the cultural center of Eastern Europe. The new capital attracted artists from Ukraine and a group of talented Ukrainian classicists, which included the painters Antin Losenko, Dmytro H. Levytsky, and Volodymyr Borovykovsky and the sculptor Ivan P. Martos, worked there. These artists contributed to the Europeanization of Russian art, but at the same time their absence from Ukraine led to a marked decline and provincialization of Ukrainian art.

In the first half of the 19th century realism began to replace classicism in Ukraine, although various academic and eclectic movements continued to flourish, as in other parts of Europe, almost to the end of the century. The rebirth of Ukrainian art is connected with Taras Shevchenko, the national bard of Ukraine, who was a painter and engraver by profession. In the 1840s he turned from the academism of Saint Petersburg to a more realistic depiction of scenes from the daily life of the peasantry, Ukrainian history, and landscapes. A number of his followers adopted this approach, giving rise to a Ukrainian ethnographic school of art. Today certain scholars regard this school as narrow and provincial, but considering the period, in which not a single Ukrainian-language school or periodical was permitted in Russian-ruled Ukraine, this art group was an important cultural phenomenon.

At the turn of the 19th century the academic tendencies in Ukrainian art gave way to impressionism. Ukrainian artists, who had formerly studied at the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts, the only academy of its kind in the Russian Empire, began to visit Western academies in Cracow, Munich, and Paris and to return home with new ideas about art. Ukrainian art exhibits began to be held, first in Lviv (under Austrian control) and then in Kyiv and other cities. A reaction against impressionism and ethnographism began early in the first decade of the 20th century, and the influence of new movements in world art became evident in Ukraine. Certain artists, such as Alexander Archipenko, became the co-founders of new stylistic trends, while others, such as Mykhailo Boichuk and members of his school, combined the new artistic ideas with older traditional forms, particularly with the Byzantine style (see Neo-Byzantinism). Boichuk’s school raised anew the problems of composition and re-established the monumental style in contemporary Ukrainian art. From the historical perspective this was one of the more interesting phenomena in 20th-century East European art. At the beginning of the 20th century there was also an effort (by such artists as Vasyl H. Krychevsky) to revive a Ukrainian style in architecture based on the Cossack baroque and on folk architecture.

One of the first actions that was taken by the new Ukrainian National Republic was to establish the Ukrainian State Academy of Arts in Kyiv, in December 1917. The academy’s faculty consisted of many prominent artists and professors. After the Soviet occupation of Ukraine in 1920 the academy was renamed the Kyiv State Art Institute. Various higher art schools were also established in Kharkiv, Odesa, and Dnipropetrovsk.

In the 1920s five artists’ associations with varying artistic and ideological profiles existed in Soviet Ukraine, but by 1932 all of them were disbanded and eventually replaced by the Union of Artists of Ukraine which was a branch of the USSR Union of Artists based in Moscow. In the 1920s Ukrainian artists had their own section in the Soviet pavilion at the Venice Biennale, but this also was eventually prohibited. The Soviet style of socialist realism was imposed on all artists in the 1930s, and many works that did not conform to the style were destroyed, while their authors were persecuted for ‘nationalism’ and ‘formalism.’ Because of this policy numerous artists from Soviet Ukraine sought refuge in the West before and after the Second World War, first in Western Ukraine and then in the displaced persons camps in Germany and Austria, from which they were resettled in the countries of Western Europe, the United States, Canada, South America, and Australia.

The development of art in Soviet Ukraine after 1945 was marked by the constant struggle between socialist realism and the desire for freedom of expression. Although the artists of Soviet Ukraine were not able to present an exhibit outside the Soviet bloc countries of the caliber of their exhibit at the Venice Biennale, they did succeed in publishing the six-volume Istoriia ukraïns'koho mystetstva (The History of Ukrainian Art, 1966–70). In this work the ancient Ukrainian icon, which as late as the 1950s was rejected as idealist and bourgeois, was rehabilitated as part of folk art. Overstepping the bounds of socialist realism, the Ukrainian artists of the Soviet bloc scored their main achievements in graphic art and decorative art—mosaics, majolica, and ceramics—where the materials used do not permit realistic representation and allow for simplification and stylization.

After the initial economic and cultural difficulties of resettlement, the Ukrainian artists in the West began to participate in the artistic life of their new homelands. The Ukrainian artistic community abroad consists of three generations of artists: those born and trained in Ukraine, those born in Ukraine and trained in the West, and those born and trained in the West. These artists have their own associations, art schools, institutes, and galleries. Although their contributions were not recognized officially in Soviet Ukraine, many of them deserve a lasting place in the history of Ukrainian art.

(See Architecture, Graphic art, Painting, and Sculpture for additional information and bibliography.)

Sviatoslav Hordynsky

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 1 (1984).]