Skoropadsky, Pavlo

Skoropadsky, Pavlo [Skoropads’kyj], b 15 May 1873 in Wiesbaden, Germany, d 26 April 1945 in Metten, Bavaria. Ukrainian noble, general, and statesman; scion of the Skoropadsky family. He grew up on his father's estate in Trostianets (Pryluky county, Poltava gubernia), studied at the Starodub gymnasium, and graduated from the elite Page Corps cadet school in Saint Petersburg. He served in a cavalry guard regiment and commanded a company of the Chita Cossack Regiment in the Russo-Japanese War. He was appointed aide-de-camp to Emperor Nicholas II in 1905, a colonel in 1906, commander of the 20th Finnish Dragoon Regiment in 1910, and a major general and commander of a cavalry regiment in the emperor's House Guard in 1911. During the First World War he commanded the 1st Brigade of the 1st Cavalry Guard Division, then the 5th Cavalry and 1st Cavalry Guard divisions, and the 34th Army Corps (at the rank of lieutenant general).

After the February Revolution of 1917 Skoropadsky oversaw the Ukrainization of the 34th Corps as the 1st Ukrainian Corps (see Army of the Ukrainian National Republic). He was elected honorary otaman of the Free Cossacks at their first congress in October 1917. In October–November of that year the disciplined 60,000-man First Corps and the Free Cossacks under his command controlled the Vapniarka–Zhmerynka–Koziatyn–Shepetivka railway corridor. It disarmed and demobilized pro-Bolshevik military units returning from the southwestern and Romanian fronts and thereby prevented them from attacking Kyiv and plundering Ukraine. As an opponent of the Central Rada's socialist policies (especially its agrarian reforms) Skoropadsky initiated a right-wing conspiracy known as the Ukrainian People's Hromada, consisting of his fellow noble landowners and loyal officers. Its plans to overthrow the Rada and establish an authoritarian state ruled by the Skoropadsky family gained the support of the Ukrainian Democratic Agrarian party and the All-Ukrainian Union of Landowners. On 24 April 1918 Skoropadsky was assured by Gen Wilhelm Groener, the German chief of staff, that the German army would support a coup d'état.

On 29 April 1918 the German-backed coup proved successful. Skoropadsky was proclaimed hetman of the Ukrainian State (as the Ukrainian National Republic [UNR] was renamed) at an agrarian congress convened by the Union of Landowners. The Central Rada and all land committees were dissolved, all UNR ministers were removed, the Rada's laws and reforms were revoked, and censorship of the press was introduced. The Hetman government appointed by Skoropadsky included members of the Russian Constitutional Democratic (kadet) party and even anti-Ukrainian Russian monarchists (who were major figures in Sergei Gerbel's November–December cabinet). The government's social and economic policies were subject to and shaped by Germany's imperialistic aims, as well as the interests of Ukraine's large landowners, industrialists, and capitalists. The Hetman government also allowed Russian anti-Bolshevik political leaders and military organizations to turn Kyiv into one of their staging areas. Ukrainian democrats refused to take part in the government, and in late May 1918 they formed the Ukrainian National-State Union (later renamed the Ukrainian National Union [UNS]) to co-ordinate political opposition. The left (including the Bolsheviks) exploited the dissatisfaction, and it soon erupted in the form of agrarian uprisings (see Partisan movement in Ukraine, 1918–22), railway and other strikes, sabotage (bombings and arson in Kyiv, Odesa, and elsewhere), and assassinations (eg, of the German field marshal Hermann von Eichhorn). The government and the German and Austrian military responded with repressive measures.

Skoropadsky's attempts in October 1918 to diffuse opposition to his regime by entering into negotiations with the Ukrainian National Union and asserting his support for Ukraine's independence from the Central Powers proved unsuccessful, and his November manifesto of federation with a future non-Bolshevik Russia only accelerated the momentum of the UNS-led popular rebellion against his regime. On 14 December 1918, after German troops abandoned Kyiv, Skoropadsky abdicated and fled to Germany via Switzerland, and his government surrendered power to the Directory of the Ukrainian National Republic.

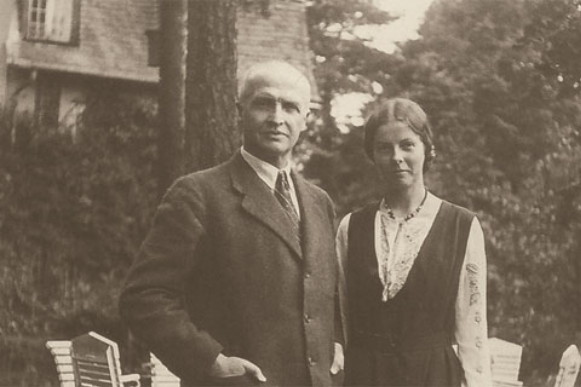

For most of the interwar years Skoropadsky lived in Wannsee, near Berlin, and received German financial support. From there he headed the hetmanite movement, consisting of monarchist émigré organizations, such as the Ukrainian Union of Agrarians-Statists in Europe, the United Hetman Organization in Canada and the United States, and the Ukrainian Hetman Organization of America. He was also honorary president of the Ukrainian Hromada society in Berlin. Because of his links with governing Junker circles, in 1926 he was able to initiate the creation of the Ukrainian Scientific Institute in Berlin. Skoropadsky never relinquished his claim to Ukraine. During the Second World War he lobbied the Nazi government for the release of the leaders of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists imprisoned in German concentration camps. He was mortally wounded during an Allied air raid on the railway station at Plattling, in Bavaria, and was buried in Wiesbaden. Excerpts from his memoirs appeared in Khliborobs’ka Ukraïna (vols 4 and 5 [1922–3, 1924–5]) and under separate cover as a 1992 Kyiv volume of his Spomyny (Reminiscences). A collection of essays about Skoropadsky and his times, edited by Olena Ott-Skoropadska, appeared in 1993 as Ostannii het’man (The Last Hetman). Skoropadsky’s memoirs regarding events from late 1917 to December 1918, edited by Jaroslaw Pelenski (who also provided a foreward) were published in 1995.

Oleksander Ohloblyn, Arkadii Zhukovsky

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 4 (1993).]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)