IEU'S FEATURED TOPICS CONCERNING THE PEOPLE OF UKRAINE AND UKRAINIANS ABROAD

I. Ukrainians and the Ukrainian Language

II. From Nobles to Peasants: Historical Estates of Ukrainian Society

III. The Expressive Culture of Traditional Ukrainian Folklore

IV. Ukrainian Folk Oral Literature

V. Ukrainian Folk Customs and Rites

VI. Ukrainian Traditional Folk Beliefs, Mythology, and Demonology

VII. Ukrainian Christmas and New Year Traditions

VIII. Traditional Handicrafts of the Ukrainian People

IX. Ukrainian Folk Musical Instruments

X. The Ukrainian Highlanders: Hutsuls, Boikos, and Lemkos

XI. The Crimean Tatars and Other Turkic-speaking Peoples of Ukraine

XII. History of the Jews in Ukraine

XIII. Romanians and Moldavians in Ukraine

XIV. The History of Russians in Ukraine

XV. Belarusians in Ukraine and Ukrainians in Belarus

XVI. The History of Ukrainians in Poland

XVII. Ukrainians in Romania

XVIII. Ukrainians in Russia (1): Ukrainian Ethnic Territories in Southwestern Russian Federation

XIX. Ukrainians in Russia (2): Ukrainians in the Kuban Region

XX. Ukrainians in Russia (3): The Far East

XXI. The History of Ukrainians in Slovakia

XXII. Ukrainians in Canada (Part 1): The Prairie Provinces

XXIII. The History of Ukrainians in the Czech Lands

XXIV. Ukrainians in South America (1): Argentina

XXV. Ukrainians in South America (2): Brazil

XXVI. Ukrainians in South America and Latin America (3): Paraguay, Uruguay, Chile, Venezuela, Mexico, and Cuba

UKRAINIANS AND THE UKRAINIAN LANGUAGE

UKRAINIANS AND THE UKRAINIAN LANGUAGE

The oldest recorded names used for the Ukrainians are Rusyny, Rusychi, and Rusy (from Rus'), which were transcribed in Latin as Russi, Rutheni, and Ruteni (later Ruthenians). In the 10th to 12th centuries those names applied only to the Slavic inhabitants of what is today the national and ethnic territory of Ukraine. Later a similar designation was adopted by the proto-Russian Slavic inhabitants of the northeastern principalities of Kyivan Rus'--Russkie (of Rus'), an adjectival form indicating that they were initially subjects of ('belonged to') Rus'. Beginning in the 16th century Muscovite documents referred to the Ukrainians as Cherkasy, alluding perhaps to the fact that in and around the town of Cherkasy there were many Cossack settlements. In the 17th- and 18th-century Cossack Hetman state the terms Malorosiiany and Malorosy, from Mala Rus' (Rus' Minor, the name introduced by the Patriarch of Constantinople in the 14th century to refer to the lands of Halych metropoly and reintroduced by Ukrainian clerics in the 17th century), became accepted by the inhabitants as their designation. Those terms were retained in a modified Russian form and used officially under tsarist rule and by foreigners (eg, Little Russia) until 1917. By the 1860s, however, some opposition to the terms became evident in Russian-ruled Ukraine, on the ground that they were as pejorative as the term khokhol. The modern name Ukraintsi (Ukrainians) is derived from Ukraina (Ukraine), a name first documented in the Kyiv Chronicle under the year 1187. The terms Ukrainiany (in the chronicle under the year 1268), Ukrainnyky, and even narod ukrainskyi (the Ukrainian people) were used sporadically before Ukraintsi attained currency under the influence of the writings of Ukrainian activists in Russian-ruled Ukraine in the 19th century. Western Ukrainians under Austro-Hungarian rule used the term 'Ukrainians' to refer to their ethnic counterparts under Russian rule but called themselves 'Ruthenians.' The appellation 'Ukrainian' did not take hold in Galicia and Bukovyna until the first quarter of the 20th century, in Transcarpathia until the 1930s, and in the Presov region until the late 1940s... Learn more about Ukrainians and the Ukrainian language by visiting the following entries:

|

UKRAINIANS. The East Slavic nation constituting the native population of Ukraine; the sixth-largest nation in Europe. According to the concept of nationality dominant in Eastern Europe the Ukrainians are people whose native language is Ukrainian (an objective criterion) whether or not they are nationally conscious, and all those who identify themselves as Ukrainian (a subjective criterion) whether or not they speak Ukrainian. Isolated attempts to introduce a territorial-political concept of Ukrainian nationality on the Western European model (eg, by Viacheslav Lypynsky) were unsuccessful until the 1990s. Because territorial loyalty has also been manifested by the historical national minorities living in Ukraine, the accepted view in Ukraine today is that all permanent inhabitants of Ukraine are its citizens (ie, Ukrainians) regardless of their ethnic origins or the language in which they communicate. The official declaration of Ukrainian sovereignty of 16 July 1990 stated that 'citizens of the Republic of all nationalities constitute the people (narod) of Ukraine.' Until the final quarter of the 19th century the Ukrainians, with few exceptions, lived on their aboriginal lands, which now, basically, constitute Ukrainian ethnic territory. In the last few decades of the 19th century Ukrainians under Russian rule began a massive emigration to the Asian regions of the empire, and their counterparts under Austro-Hungarian rule emigrated to the New World. The number of Ukrainians outside of their homeland had grown from 1 million in 1880 to over 14 million by 1989. Today more than one-quarter of all Ukrainians in the world live outside of Ukraine... |

| Ukrainians |

_s.jpg)

|

RUTHENIANS. A historic name for Ukrainians corresponding to the Ukrainian rusyny. The first use of the word Ruteni in reference to the inhabitants of Rus' was in the Annales Augustiani of 1089. (Rus' was the former name of Ukraine. In the Kyiv Chronicle the term was a collective noun referring initially to the Varangians and then to the land of the Polianians around Kyiv. Gradually it came to signify the entire realm of the grand prince of Kyiv, ie, Kyivan Rus'). For centuries thereafter Rutheni was used in Latin as the designation of all East Slavs, particularly Ukrainians and Belarusians. In the 16th century the word more clearly began to be associated with the Ukrainians and Belarusians of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as distinct from the Muscovites (later known as Russians), who were designated Moscovitae. After the partitions of Poland (1772-95) the term 'Ruthenian' underwent further restriction. It came to be associated primarily with those Ukrainians who lived under the Habsburg monarchy, in Galicia, Bukovyna, and Transcarpathia. Although the term Ruthenen remained in official use until the collapse of the Habsburg monarchy in 1918, Galician Ukrainians themselves began to abandon that name (from around 1900) in favor of the self-designation ukraintsi (Ukrainians). Since the Second World War the term 'Ruthenian' has been used as a self-designation almost exclusively by descendants of emigrants from Transcarpathia in the United States, but since the 1970s they have begun to abandon it in favor of the designation 'Rusyn' or 'Carpatho-Rusyn'... |

| Ruthenians |

|

UKRAINIAN LANGUAGE. The second most widely spoken language of the 12 surviving members of the Slavic group of the large Indo-European language family. Geographically, it is classified with Russian and Belarusian as an East Slavic language. Actually, like Slovak, it occupies a central position: it borders on some West Slavic languages, and it once bordered on Bulgarian, a South Slavic language, before being separated from it by Romanian and Hungarian. Accordingly, Ukrainian shared in the historical development of all three branches of the Slavic languages. Today Ukrainian borders on Russian in the east and northeast, on Belarusian in the north, and on Polish, Slovak, and two non-Slavic languages--Hungarian and Romanian--in the west. Before the steppes of southern Ukraine were resettled by the Ukrainians, this was an area of contact with various Turkic languages, such as Crimean Tatar. Within its geographic boundaries Ukrainian is represented basically by a set of dialects, some of which differ significantly from the others. Generally, however, dialectal divisions in Ukrainian are not as strong as they are, for example, in British English or in German. Standard Ukrainian, which is accepted as such by the speakers of all the dialects and represents Ukrainian to outsiders, is a superstructure built on this dialectal foundation. It is the only form of Ukrainian taught in school and, except for clearly regional manifestations, used in literature. The standard language is based mainly on the Poltava-Kyiv dialects of the southeastern group, but it also contains many features from other dialects, particularly the southwestern ones... |

| Ukrainian language |

|

STANDARD UKRAINIAN. The standard, or literary, version of the Ukrainian language evolved through three distinct periods: old (10th-13th centuries), middle (14th-18th centuries), and modern (19th-20th centuries). The cardinal changes that occurred were conditioned by changes in the political and cultural history of Ukraine. Old Ukrainian is found in extant Kyivan Rus' church and scholarly texts dating from the mid-11th century and the Kyivan charter of 1130, in Galician church texts dating from the late 11th century, and in Galician charters dating from the mid-14th century. The language of all these genres is basically Church Slavonic, with an ever-increasing admixture of local lexical, phonetic, morphological, and syntactic features. Although the language was not institutionally regulated, it remained quite stable, because of the patronage of the church and the concentration of literary life around religious centers. The decline of Kyivan Rus' and later the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia and the resulting annexation of most Ukrainian lands (except for Galicia, Bukovyna, and Transcarpathia) by Lithuania interrupted the literary tradition of Old Ukrainian. This is particularly evident in the rift that occurred between the language of the church and that of government. The political division of the Ukrainian lands between Poland and Lithuania led to the development of two variants of administrative language, Galician and Volhynian-Polisian. The growth of towns, the rise of a Ukrainian burgher class, and the influence of the Reformation brought about a shift in the language of the higher genres toward the chancery and vernacular languages. There were even attempts at translating the Bible into a language approximating the vernacular... |

| Standard Ukrainian |

|

CYRILLIC ALPHABET (kyrylytsia). Slavic system based on the Greek majuscule script. When, after their expulsion from Moravia in 885, the disciples of Saint Cyril and Saint Methodius settled in Bulgaria, they had recourse to the Greek alphabet as a replacement for the Glagolitic alphabet developed by Saint Cyril. The Greek alphabet was adapted to Slavic and supplemented by letters from the Glagolitic that rendered phonemes lacking in the Greek language. The original Cyrillic alphabet had 36 to 38 letters, some of which were used only, or primarily, in the writing of Greek words. With the expansion of eastern Christianity, the Cyrillic alphabet spread from Bulgaria to other Slavic lands. The Cyrillic alphabet (with certain modifications) is still used today in the Ukrainian, Russian, Belarusian, Bulgarian, Macedonian, and Serbian writing systems... |

| Cyrillic alphabet |

|

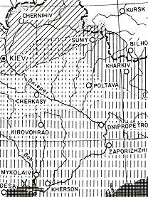

DIALECTS. Ukrainian dialects are classified into two basic groups--the northern (Polisian) and the southern dialects--between which there extends a wide belt of 'transitional' dialects, southern dialects on northern foundations (that is, historically northern dialects that were assimilated by southern dialects). The northern dialectal group is subdivided into the following dialects: the east Polisian (east of the Dnipro River), the central Polisian (between the Dnipro and the Horyn River), the west Polisian (between the Horyn and the Buh River and Lisna River), and the Podlachian dialects. The southern group of dialects is divided into two subgroups: the more uniform southeastern dialects (central Dnipro dialects, Slobidska Ukraine dialects, and steppe dialects) and the southwestern dialects, which are highly differentiated. The southwestern group is composed of the following dialects: South Volhynian dialects, Podilian dialects, Dnister dialects, Sian dialects, Bukovyna-Pokutia dialects, Hutsul dialect, Boiko dialect, Middle-Transcarpathian dialects, and Lemko dialects. After the Ukrainian literary language, ie, Standard Ukrainian, stabilized in the 19th century, the use of dialects came to characterize primarily the peasantry. But in the course of the 20th century, with the influence of the church, education, the press, and radio, elements of the literary language began, and continued increasingly, to penetrate even the language of the peasants... |

| Dialects |

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries about Ukrainians and the Ukrainian language were made possible by the financial support of the SENIOR CITIZENS HOME OF TARAS H. SHEVCHENKO (WINDSOR) INC. FUND.

II. FROM NOBLES TO PEASANTS: HISTORICAL ESTATES OF UKRAINIAN SOCIETY

II. FROM NOBLES TO PEASANTS: HISTORICAL ESTATES OF UKRAINIAN SOCIETY

The beginning of the estate system in Western Europe can be traced to the 12th-13th century and in Central and Eastern Europe, including Ukrainian territories, to the 13th-14th century. The clearest example of an estate structure (affecting Ukrainian lands) was found in the social order of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. There the higher aristocracy consisted of princes and magnates who were descended from princes or notable boyars. The lower boyars, large landowners, and distinguished warriors organized themselves under Polish influence into the nobility (shliakhta), which at the end of the 15th and the beginning of the 16th century was the most influential estate in society. From 1522 to the Union of Lublin (1569) the nobility of Lithuania evolved gradually into a closed, politically influential estate. A magnate oligarchy, which determined the policy of the Polish Commonwealth, arose within this estate. Several Polonized Ukrainian families belonged to this oligarchy. In theory the Ukrainian clergy, both Orthodox and Uniate, belonged to the clerical estate, but only certain church hierarchs and archimandrites possessed the political rights of their estate, the common clergy being treated rather like the peasantry. In the later 16th century a new and more distinctly defined estate--the burghers--became an important political force. Consisting of merchants and artisans, the burgher estate gained certain individual and corporate privileges set down in Magdeburg law. Among the collective privileges was the right to municipal self-government. Although it was the largest social group, the peasantry did not possess rights similar to those of the burghers. The peasants were economically and legally dependent on their feudal lords and on the nobility, and in this context they cannot be treated as a separate estate. The position of the Ukrainian peasantry was somewhat different, because part of it participated in colonizing the frontier and thus received certain favors. In the steppes of eastern and southern Ukraine a special social group--the Ukrainian Cossacks--arose. The Cossack-peasant rebellions of the 16th and 17th centuries were a manifestation of the conflict between the two models of the estate system--the Polish nobility model and the Ukrainian Cossack model... Learn more about the historical estates of Ukrainian society by visiting the following entries:

|

ESTATES. Closed social groups that originated in the medieval period and survived in various forms until the mid-19th century. Members of each estate enjoyed certain rights or privileges and fulfilled various duties towards the sovereign and other members of their estate. The estates differed in social function and economic status; they were basically legally defined entities. Each estate was an autonomous group, with its own courts and administration and its own representation at the level of state government. Membership in a given estate was hereditary, and mobility from one estate to another was difficult, although not impossible. Only the admission to the clerical estate, which was purely functional, was open, although in the Eastern church, where the clergy could marry, there existed a semihereditary estate. The principal estates were the nobility, the clergy, the burghers, and the free peasantry. Most historians do not detect clear attributes of the estate system in the society of Kyivan Rus'. Apart from the princes, the social groups of Rus' differed rather in economic status, service obligations, and social function than in hereditary rights. In Galicia-Volhynia the boyars and the leading members of the princely retinue organized themselves into a separate estate after the example of the aristocracy in Poland and Hungary. Yet, in Galicia the estate system was firmly established only in the 15th century when Rus' law was replaced by Polish law... |

| Estates |

|

NOBILITY. The privileged and titled elite class of society. The concept of a noble class is largely a European one that developed out of the feudal experience. In Eastern Europe the nobility as a social elite with inherent rights established itself most strongly in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In Ukraine, after the Princely era, the existence of a distinctive elite class of native nobles was largely pre-empted by the country's domination first by Poland and then by the Russian Empire (which prompted the considerable assimilation of Ukraine's upper class by foreign aristocracies). The notable exceptions to that long-standing state of affairs could be found in the Lithuanian-Ruthenian state, where Orthodox Ukrainian nobles constituted a distinctive subgroup of the aristocracy, and in the Hetman state, where the Cossack starshyna was developing into a noble class. The aspirations of the Cossack starshyna was increased in 1743, when their legal compendium established that descendants of appointed or hereditary nobles registered under the former state were entitled to nobility within the Russian Empire. As a result of the assimilation of the Ukrainian nobility, the social structure of Ukraine was truncated for many years, and Ukrainian society was left without a leading element. Nevertheless, individual noblemen emerged at various times as key figures in the defence of Ukrainian social, religious, and political rights... |

| Nobility |

|

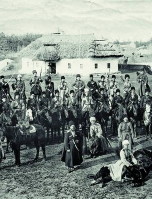

COSSACKS. Because of the conjunction of certain geographic and social conditions, a special social group--the Ukrainian Cossacks--arose in Ukraine as an attempt of the Ukrainian population to liberate itself from under the control of the nobility. The name Cossack (Ukrainian: kozak) is derived from the Turkic kazak (free man). By the end of the 15th century this name was applied to those Ukrainians who went into the steppes to practice various trades and engage in hunting, fishing, beekeeping, and so on. The history of the Ukrainian Cossacks has three distinct aspects: their struggle against the Tatars and the Turks in the steppe and on the Black Sea; their participation in the struggle of the Ukrainian people against socioeconomic and national-religious oppression by the Polish magnates; and their role in the building of an autonomous Cossack state. The growth of Cossackdom posed a dilemma for the Polish government: on the one hand the Cossacks were necessary for the defense of the steppe frontier; on the other hand they presented a threat to the magnates and the nobles, who governed the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The Polish offensive against the Cossacks, together with intensified socioeconomic and national-religious oppression of the other classes of Ukrainian society, resulted in the outbreak of the Cossack-Polish War in 1648 led by Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky and the consequent establishment of the Hetman state... |

| Cossacks |

|

CLERGY. From earliest times in the Christian church the clergy has constituted a group sharply differentiated from the laity by being initiated into the service of God through the sacrament of ordination (laying on of hands). In the Ukrainian Orthodox church and the Ukrainian Catholic church, the clergy is divided into the lower (deacons, priests) and higher (the hierarchy or episcopate) clergy and into the secular (white) and regular (black) clergy. The secular clergy lives 'in the world,' among the people, and fulfils its spiritual functions among them in their religious communities. The regular clergy, having renounced the world, lives in monasteries and devotes itself to prayer and works of Christian charity (schools, shelters, hospitals, and the like)... The legal position of the clergy in Kyivan Rus' derived from the self-government of the church. The clergy constituted a social class with its own courts, whose jurisdiction extended not only to the priests, but also to groups associated with the church. Church property was exempt from state taxes. But the status of the Ukrainian clergy declined significantly during the Polish-Lithuanian period, first in the lands under Polish rule and then in the Lithuanian-Ruthenian state. Under Poland, and especially in Galicia, the Ukrainian clergy was merely tolerated, for all the estate privileges were reserved for the Roman Catholic clergy as representatives of the interests of the foreign power on Ukrainian soil... |

| Clergy |

|

BURGHERS. In the broad sense of the term, urban dwellers employed in various skilled trades, industries, and commerce, as well as suburban residents employed in farming. In the narrow sense, which is particularly applicable to Ukraine, burghers were a social stratum that used to be self-governing and then became 'tax-paying estate' of the Russian Empire in the 19th and 20th centuries. In Kyivan Rus' the burghers were not legally defined, even though they constituted a socially and economically distinct stratum. The elite upper-stratum were prominent men, city elders, and wealthy merchants; in the middle were the merchants; beneath them were the commoners. The burghers became a separate stratum in Galicia-Volhynia at the end of the 13th century, and particularly under Polish- Lithuanian rule, when Magdeburg law was granted to many cities in Ukraine. During this period a distinct hierarchy, consisting of patricians, middle burghers, and plebeians, emerged among the burghers. In Western Ukraine this division was complicated by national-religious differences. As a result, different groups of burghers had different rights; for example, non-Catholic burghers (Orthodox Ukrainians, Armenians, Jews) lost the right to elect their own representatives to the city council and to certain guilds. In spite of social and national-religious discrimination, the Ukrainian burghers formed the leading stratum in the towns of the 16th and 17th centuries... |

| Burghers |

|

PEASANTS. The peasants of Kyivan Rus' arose in conjunction with the new state system that replaced the disintegrating ancestral social structure of the Slavic tribes. The peasants of Rus' were grouped in relatively autonomous settlements, where they worked together to cultivate land using slash-and-burn techniques. The vast majority of peasants fell into the category of smerds. The smerds were of two types, either entirely free or dependent. The free peasants formed the largest group and enjoyed the rights of free persons. The dependent smerds, whose numbers grew with princely gifts of land to servitors, lived on princely and boyar lands, paying rents primarily in kind. After the Mongol invasion (1240) and the passage of Ukrainian lands under Polish and Lithuanian rule (mid-14th century) the peasants' rights were further restricted and their rents increased, until they lost their personal freedom and became serfs wholly dependent on the landowners. Ukrainian peasants resisted enserfment (eg, the Mukha rebellion in 1490-2), but they were forced to submit. They sometimes ran away from their owners' estates and headed for the steppe of Southern Ukraine, where they became Cossacks... In the 19th century, the peasants played a major role in the revival of the Ukrainian nation, when the Ukrainian literary language was reconstructed on the basis of the peasant vernacular, and the traditions of village life were mined for the components of a national culture... |

| Peasants |

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries associated with the historical estates of Ukrainian society were made possible by the financial support of the CANADIAN FOUNDATION FOR UKRAINIAN STUDIES.

III. THE EXPRESSIVE CULTURE OF TRADITIONAL UKRAINIAN FOLKLORE

III. THE EXPRESSIVE CULTURE OF TRADITIONAL UKRAINIAN FOLKLORE

Ukrainian folk oral literature, poetry, and songs (including epic historical songs and dumas) are among the most distinctive ethnocultural features of Ukrainians as a people. The particularly vital role of folklore in the formation of modern Ukrainian culture and national consciousness was the result of an unusually important role that peasantry played in the history of Ukraine. Not only did peasants make up the overwhelming majority of the Ukrainian population until the 1930s, but they also contributed much to the preservation and development of the Ukrainian language and traditional way of life. Their conservative attitude toward traditions, language, and faith--in short, their fostering of national and ethnic characteristics, some of which extend back to pre-Christian times and even to Indo-European roots--was of great importance for the Ukrainian nation, which had been subdued by powerful neighbors and, particularly in the case of the upper classes and the urban strata, exposed to assimilatory influences. In the 19th century, folk songs and folk oral literature not only served as the basis for the reconstruction of the Ukrainian literary language, but also provided Ukrainian writers, composers, and intellectuals with the components for the creation of a modern national culture. Apart from collecting and studying works of Ukrainian folk oral literature, the leading Ukrainian cultural figures and intellectuals have also been fascinated with the richness of Ukrainian folk customs and such aspects of traditional folk culture as dances, regional costumes, folk art, and unique folk architecture... Learn more about the expressive culture of traditional Ukrainian folklore by visiting the following entries:

|

FOLKLORE. In Ukrainian folklore scholarship there is an overwhelming tendency to equate folklore with folk oral literature. In this discipline folk tales (tales of magic, animal tales, legends, anecdotes, etc), folk songs (ritual songs and non-ritual songs), and items of the minor verbal genres (proverbs and riddles) have been collected and studied. Some of the above (animal tales, some songs and games, and certain types of proverbs and riddles) are children's folklore. Oral literature consists of variant texts whose authorship is unknown, the texts being passed along by word of mouth and in the process changed to some degree by each performer. Some descriptions of Ukrainian folklore originated back in the Middle Ages. Pre-Christian Ukrainian folk customs and rites were described in medieval Arabic and Byzantine sources. Other documentation of Ukrainian folklore is found in the earliest of literary monuments in Ukraine (ie, the chronicles and Slovo o polku Ihorevi), where instances of folk prose, proverbs, and ritual songs can be found. Christianity introduced into Ukraine not only dogma but also apocryphal and classical folklore traditions. A systematic study and publication of Ukrainian oral folklore originated in the 19th century, and the largest organized folklore collecting took place then under the leadership of Pavlo Chubynsky...

|

| Folklore |

|

FOLK ORAL LITERATURE. The sum of oral works, both poetry and prose, which are produced usually by anonymous authors and are preserved in the people's memory for a long time by being passed on orally from generation to generation. Ukrainian folk oral literature has its distinctive artistic qualities, its unique poetic devices--metaphors, similes, epithets, and symbolism. The poetic folk literature consists mostly of folk songs, which are subdivided into various genres. Folk prose can be divided into fables, fairy tales, stories, legends, anecdotes, and others. Poetic-prose folk literature consists of spells, proverbs, sayings, and riddles. In the 19th century the works of folk oral literature were held to be the products of a collective popular mind. Today folklorists favor the theory that individuals are the creators of the oral tradition. With the coming of Christianity and the church's rejection of folk literature and folk customs as pagan relics, folk oral literature nevertheless managed to retain its vitality and to absorb the Christian influences of medieval written literature. Beginning with the Renaissance and baroque periods there was a constant interchange between oral and written literature. Mixed folklore-literary genres of the baroque appeared, such as interludes, through which Christmas, Easter, and satirical verse passed into folklore... |

| Folk oral literature |

|

FOLK SONGS. The song is one of the oldest and most prevalent forms of folklore. It unites a poetic text with a melody. The poetic imagery determines the character and emotive quality of the melody. Songs usually have a well-defined strophic structure: all stanzas are set to the same melody as the first stanza. Each stanza is often followed by a refrain. Folk songs are usually monodic choral songs, but Ukrainian folk songs are exceptional for their rich polyphony. The folk songs express the common experience of the Ukrainian people: all the important events in life from the cradle to the grave are accompanied by song. By their content and function folk songs can be divided into four basic groups: (1) ritual songs; (2) harvest songs and wedding songs; (3) historical and political songs, such as dumas and ballads; and (4) lyrical songs. Chumak songs, wanderers' songs, and cradle songs belong to separate groups. Together these genres of folk song encompass the variegated life of the Ukrainian people. The universal content and the artful clarity of expression of Ukrainian folk songs account for their survival for many centuries. In many songs--historical, social--the epic and lyrical elements form an organic unity. In numerous Ukrainian folk songs nature manifests human emotions.... |

| Folk songs |

|

FOLK CUSTOMS AND RITES. Ritual actions and verbal formulas belonging to the traditions of familial, tribal, and folk life and connected with the changing seasons and the resulting changes in agricultural or other work. These customs and rites are regulated by the folk calendar and are often accompanied by magical acts, religious ceremonies, incantations, folk songs, dances, and dramatic plays. They arose in prehistoric times and evolved through the centuries of Ukrainian history, blending in many cases with Christian rites. They can be divided into: (1) familial customs and rites, which consist of birth, wedding, and burial rites; (2) seasonal-productive customs and rites, which are tied to farming, herding, and hunting tasks; and (3) communal customs and rites, which mark certain events in the life of the community. With the spread of modern civilization and urban culture, as well as the changes triggered by the two world wars, the folk customs and rites in Ukraine have been greatly transformed. However, Soviet efforts to eradicate them did not succeed. Believers continued to practice the folk customs of the Christian calendar, particularly those of Christmas and Easter, while the country people were turning to ancient folk rites such as New Year's rites... |

| Folk customs and rites |

|

FOLK DANCE. In prehistoric and ancient times dance was a ritual means of communicating with nature and the divine forces. Only isolated elements of ancient folk calendar ritual and cult dances have survived through the centuries. With the introduction of Christianity in Ukraine, the archaic relics of these dances blended with Christian rituals and were adapted to the church calendar and Christian festivals. Ancient Ukrainian dances were actually agricultural dance games (khorovody); their basic form was the circle, associated with the cult of the sun, the greatest life-giving power. The most widely known are the spring khorovody (circular choral dances). In the summer the dances of the Kupalo festival were performed. In the late summer and early autumn the harvest feast was celebrated by circular dances, which constituted a dramatization of the song content and an imitation of agricultural work. The pre-Lenten carnival period was also the time for weddings, which have in part preserved the traditional ritual character of dance. Ukrainian ritual dances are performed mostly to the accompaniment of a churchlike, antiphonic chant. They are rarely performed to music. In general, Ukrainian folk dances can be divided into two groups: those performed to the accompaniment of songs and those performed to music... |

| Folk dance |

|

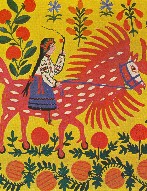

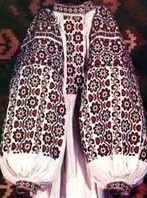

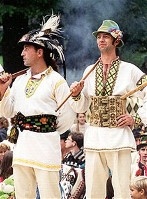

FOLK COSTUMES. In general, Ukrainian folk dress can be classified into five regional groups. The people of the Middle Dnipro River region, including the Left-Bank and steppe areas, dressed in clothes originating in the Cossack Hetmanate period. In the second region, Polisia, very old features of dress, dating back to the Princely era, have been preserved. In general, women wore an embroidered blouse with a predominance of red, a colorful woven skirt, and a white headband; men wore a shirt outside the trousers and a white or gray coat. In the third region, Podilia, women wore a multicolored embroidered blouse, a rectangular, woven wraparound skirt, and a coat of dark woolen cloth; men wore a mantle, coat, short woolen overcoat, and sheepskin coat. The fourth region, consisting of central Galicia and Volhynia, preserved many old features of dress but also displayed foreign influences. The extensive use of linen in men's and women's outerwear is distinctive of this region. The fifth region encompasses the Carpathian Mountains and Subcarpathia and can be subdivided into four districts--Pokutia and Bukovyna, the Hutsul region, the Boiko region, and the Lemko region. The clothing of the Hutsul area was particularly distinguished by its vivid colors and rich ornaments... |

| Folk costumes |

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries about the expressive culture of traditional Ukrainian folklore were made possible by the financial support of the CANADIAN FOUNDATION FOR UKRAINIAN STUDIES.

IV. UKRAINIAN FOLK ORAL LITERATURE

IV. UKRAINIAN FOLK ORAL LITERATURE

The traditional scholarship of Ukrainian folklore has paid special attention to folk oral literature, at times effectively equating folklore with the rich complex of folk tales, folk songs (ritual and non-ritual songs), and items of minor verbal genres (such as proverbs and riddles). Folk oral literature is the sum of oral works, both poetry and prose, which are produced usually by anonymous authors and are preserved in the people's memory for a long time by being passed on from generation to generation by word of mouth and in the process changed to some degree by each performer (storyteller, singer, etc). Ukrainian folk oral literature has its distinctive artistic qualities, its unique poetic devices--metaphors, similes, epithets, and symbolism. The poetic folk literature consists mostly of folk songs, which are subdivided into various genres: ritual songs (songs associated with spring rituals, including vesnianky-hahilky, carols, shchedrivky, Easter songs, Kupalo festival songs, harvest songs, wedding songs, and funeral songs), historical songs and dumas (which are often quite complex and sophisticated), lyrical songs, and dance songs. Folk prose can be divided into fables, fairy tales, tales of magic, animal tales, stories, legends, anecdotes, and others. Poetic-prose folk literature consists of spells, proverbs, sayings, and riddles. The first systematic recording and publication of Ukrainian oral folklore took place at the beginning of the 19th century. Inspired by the Romantic interest in folklore and history, the process of rediscovering folk oral literature profoundly influenced the development and growth of Ukrainian literature written in the vernacular Ukrainian language and greatly contributed to the formation of modern Ukrainian national identity and consciousness... Learn more about the Ukrainian folk oral literature by visiting the following entries:

|

FOLK ORAL LITERATURE. In the 19th century the works of folk oral literature were held to be the products of a collective popular mind. Today folklorists favor the theory that individuals are the creators of the oral tradition. In the basic examples of ancient folk oral literature, however, the words are associated with ritual actions. The basic changes that occur in the works of the oral tradition are caused by their dissociation from the original ritual contexts. The verbally conveyed image that is divorced from the ritual loses its original practical motivation and either becomes forgotten or else acquires a new motivation and begins a new life. Thus, with the coming of Christianity and the church's rejection of folk literature and folk customs as pagan relics, folk oral literature nevertheless managed to retain its vitality and to absorb the Christian influences of medieval written literature. Beginning with the Renaissance and baroque periods there was a constant interchange between oral and written literature. Mixed folklore-literary genres of the baroque appeared, such as interludes, through which Christmas, Easter, and satirical verse passed into folklore. The Ukrainian populist movement of the 19th century declared folk oral tradition as the norm for all literature, while literature of the beginning of the 20th century systematically grew closer to the folk roots by absorbing certain elements of the language, genres, and content of the folk tradition...

|

| Folk oral literature |

|

DUMAS. Lyrico-epic works of folk origin about events in the Cossack period of the 16th-17th century. The dumas differ from other lyrico-epic and historical poetry by their form and by the way in which they were performed. They did not have a set strophic structure, but consisted of uneven periods that were governed by the unfolding of the story. Each period constituted a finished, syntactical whole and conveyed a complete thought. Rhyme played an important role. The dumas were not sung, but were performed in recitative to the accompaniment of a bandura, kobza, or lira. The chanting had much in common with funeral lamentation. Scholars connect the dumas with the poetic forms that appeared in Ukraine in the 12th century, such as Slovo o polku Ihorevi (The Tale of Ihor's Campaign). One widely accepted theory of the origin of the dumas is that proposed by Pavlo Zhytetsky, according to which they were a unique synthesis of popular and 'bookish-intellectual' creativity. The dumas were based on folk songs, modified by the influence of the syllabic poetry produced in the schools of the 16th-17th century. The vernacular Ukrainian language of the dumas retains many archaisms and Church Slavonic expressions. The dumas can be divided into two thematic cycles. The first and older cycle consists of dumas about the struggle with the Tatars and Turks. The second cycle consists of dumas about the Cossack-Polish struggle... |

| Duma |

_s.jpg)

|

HISTORICAL SONGS. A genre of folk songs that presents historical events and individuals in a generalized, artistic manner with details, names, and facts that may be inaccurate. Ukrainian historical songs appeared at the same time as the dumas, and perhaps even preceded them. They differ from the dumas in that they describe concrete historical events and figures; their story line is less developed, their emotive range is greater, and in them the lyrical element prevails over the epic element. The oldest cycle of historical songs dates back to the 16th century and depicts the Cossacks' struggle against the Tatars and Turks; the best known are the songs about Baida (Dmytro Vyshnevetsky) of 1564, the capture of Varna of 1605, and the siege of the Pochaiv Monastery of 1675. A second cycle consists of songs about the Cossacks' struggle against Poland; the best known are the songs about Bohdan Khmelnytsky, the Battle of Zhovti Vody, the Battle of Berestechko, the curse on Khmelnytsky for the Tatar captivity of 1653, and about Danylo Nechai, Maksym Kryvonis, and Stanyslav Morozenko. A third cycle deals with Russian oppression and includes songs about construction work on the Saint Petersburg canals, the destruction of the Zaporozhian Sich, and the death of a Cossack in Russian captivity. A fourth cycle consists of songs about the Haidamaka uprisings. There is also a large corpus of songs describing Cossack daily life... |

| Historical songs |

|

LEGENDS. In the Western tradition a legend was originally a text about the life of a saint that was prescribed reading in churches on that saint's day and during meals in monasteries. Because medieval legends were similar to fairy tales, the term was extended to refer to various kinds of tales (historical, folk, and religious). Now the term is used for tales in which the characters are actual historical personages, including saints. In Ukraine, in addition to religious legends and apocrypha, there were also legends about Rus' princes, Cossacks, hetmans, haidamakas, opryshoks, and other famous people (eg, Marusia Churai, Hryhorii Skovoroda, Taras Shevchenko). They were published by Panteleimon Kulish in his Zapiski o Iuzhnoi Rusi (Notes on Southern Rus'), by Oleksander Afanasiev-Chuzhbynsky in his Narodnye legendy (Folk Legends 1859 and 1921), and, chiefly, by researchers of Ukrainian fairy tales, such as Pavlo Chubynsky, Mykhailo Drahomanov, and Volodymyr Hnatiuk. Manuscripts of folk legends were collected and edited by Ivan Franko and published in 1899. The historical legends that appeared in the oldest Ukrainian chronicles were collected by F. Giliarov and published in 1878. Many legends became part of the Cossack chronicles. Istoriia Rusov could be considered a historical legend. Legends have reappeared in the historical novel and drama, and folk legends are frequently drawn upon in Ukrainian poetry... |

| Legends |

|

PROVERBS (prykazky, prypovidky, pryslivia). Brief, pithy popular maxims which are often rhymed and easily remembered. Dating back to prehistoric times, they typically express a universal concept through a concrete image, often with a dash of humor. Proverbs are part of the oral rather than the literary tradition. Proverbs deal with various aspects of life and are said to constitute an encyclopedia of popular wisdom. Their principal themes are nature, farming, flora and fauna, domestic life, human nature, family and social relations, customs, folk wisdom, religion, and morality. In content and form they are similar to adages, folk metaphors, puns, and fables. Because of their simple structure they can be memorized easily. Usually they consist of two symmetrical sections that rhyme. Proverbs can be found in the literary monuments of Kyivan Rus', such as the Primary Chronicle and Slovo o polku Ihorevi (The Tale of Ihor's Campaign). The first written collections of Ukrainian proverbs did not appear until the late 17th century. In the 19th century, Ivan Yuhasevych-Skliarsky's collection of 370 Ukrainian proverbs from Transcarpathia, published in 1809, was unique in its time. The first printed collection, of 618 Ukrainian proverbs, was published in Kharkiv in 1834. The second collection, of 2,715 Galician proverbs, was published in Lviv in 1841. To this day Ivan Franko's collection of over 30,000 proverbs published in 6 volumes in 1901-10 has not been surpassed... |

| Proverbs |

|

RIDDLES (zahadky). Mystifying or puzzling questions that are posed as a game and answered by guessing. Most folk riddles are aphoristic expressions in which the subject to be identified is depicted by a mere metaphor. Some are nonmetaphorical; they consist of a partial description of the subject that is to be identified. Riddles are the simplest form of folk oral literature. In the past, when most of the Ukrainian population was illiterate, riddles played an important role in the life of the peasants. A person's knowledge of riddles and ability to solve them was accepted as an indication of his or her intelligence. A candidate to a bachelors' group was often required to answer publicly a series of riddles before he was accepted. At a wedding the best man or the master of ceremonies answered riddles for the groom. Riddles were among the games played by young people at evening gatherings and at collectively undertaken tasks. In the Middle Ages a correct answer to a riddle sometimes saved a condemned man from death. In ancient times riddles were believed to have magical powers. During courtship a suitor would address the family of the courted girl in riddles to deceive the evil spirits. Riddles are an important component of spells, carols, rusalka songs, wedding songs, funeral rituals, legends, and anecdotes. Riddles appear throughout Ukrainian literature, in the works of Hryhorii Skovoroda, Ivan Kotliarevsky, Taras Shevchenko, etc... |

| Riddle |

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries featuring the Ukrainian folk oral literature were made possible by the financial support of the SENIOR CITIZENS HOME OF TARAS H. SHEVCHENKO (WINDSOR) INC. FUND at the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies.

V. UKRAINIAN FOLK CUSTOMS AND RITES

V. UKRAINIAN FOLK CUSTOMS AND RITES

The Ukrainian folk culture displays a particularly rich array of customs, ritual actions, and verbal formulas belonging to the traditions of familial, tribal, and folk life and connected with the changing seasons and the resulting changes in agricultural work. These customs and rites are regulated by the folk calendar and are often accompanied by magical acts, religious ceremonies, incantations, songs, dances, and dramatic plays. They arose in prehistoric times and evolved through the centuries of Ukrainian history, blending in many cases with Christian rites. With the spread of modern civilization and urban culture, the folk customs and rites in Ukraine have been greatly transformed. Soviet efforts to eradicate them have not succeeded. In 1970s and 1980s an increasingly persistent effort was made to revive folk rites, particularly in the family and communal sphere. Believers continued to practice the folk customs and rites of the Christian calendar, particularly those of Christmas and Easter, but the country people were turning to ancient folk customs and rites such as New Year's rites and its special carols (shchedrivky); spring rituals and songs (vesnianky-hahilky); the procession of nymphs (mavkas) and Kupalo festival, which are associated with harvest celebrations (obzhynky); wedding rites, with their ritualized dramas; celebrations of birth, involving godparents and christening linen; and farewells to army or labor recruits. These customs and rites, like the Christianized customs and rites, are steeped in tradition and are tied to ancient ancestral beliefs, symbols, and images... Learn more about the Ukrainian folk customs and rites by visiting the following entries:

|

FOLK CUSTOMS CONNECTED WITH BIRTH. Such customs have survived since ancient times. When a child was born, a ritual nativity banquet was held. The church tried to suppress these feasts for many centuries, but they have survived with all the old folk rituals. When labor began, the husband summoned a midwife. On entering the patient's house, the midwife bowed 30 times and performed an introductory ritual while uttering her prayers. A godfather (kum) and godmother (kuma) were invited for the baptism. The newborn infant was carefully protected from all kinds of evil by being kept behind a veil, out of sight not only of strangers but even of family members. The baptism was a ritual salvation of the infant from the forces of evil. Forty days after birth the mother submitted to a cleansing ritual, and the child was admitted to the church: the mother brought the infant to church and waited in the women's vestibule until after the cleansing prayers were read over her. A year or more after birth the child underwent a ritual haircutting. All the customs surrounding birth originated in pre-Christian times but were assimilated by the church... |

| Folk Customs Connected with Birth |

|

SPRING RITUALS. Traditional folk rituals practiced in the spring, from the equinox (20-21 March) to the summer solstice (21-22 June). Originally these rituals were believed to possess magical powers that ensured a bountiful harvest and fertility in domestic animals. The ritual cycle began with the rite of provody (bidding winter farewell and welcoming spring), just before the beginning of Lent. Winter was usually personified by minor deities (Kostrub, Morena, Smertka, or Masliana) effigies of which were burned or drowned ceremonially. Spring was personified by a young girl crowned with a wreath and holding a green branch in her hand. She was the central figure in the ritual games, dances, and songs (vesnianky-hahilky). The arrival of migratory birds signaled the beginning of the spring festival called Stricha (from 'greeting'). On the Feast of the 40 Martyrs (22 March) bird-shaped buns called zhaivoronky (larks) were baked and tossed into the air by children and told to bring spring with them. The largest number of agrarian rituals was designated for the Lenten period and Easter, including the ritual first sowing, the first release of livestock to pasture, and the decorating of fields and farmhouses with green branches (Rosalia)...

|

| Spring Rituals |

|

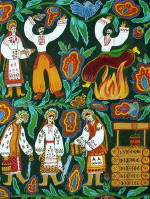

KUPALO FESTIVAL. A Slavic celebration of ancient pagan origin marking the end of the summer solstice and the beginning of the harvest (midsummer). In Christian times, the church tried to suppress the tradition, substituting it with the feast day of the Nativity of Saint John the Baptist (24 June), but it remained firmly part of folk ritual as the festival of Ivan Kupalo. Kupalo was believed to be the god of love and of the harvest and the personification of the earth's fertility. According to popular belief, 'Kupalo eve' was the only time of the year when the earth revealed its secrets and made ferns bloom to mark places where its treasures were buried, and the only time when trees spoke and even moved and when witches gathered. It was also the only time of the year when free love received popular sanction. On the eve unmarried young men and women gathered outside the village in the forest or near a stream or pond. There they built 'Kupalo fires'--a relic of the pagan custom of bringing sacrifice--around which they performed ritual dances and sang ritual songs, often erotic. They leaped over the fires, bathed in the water (an act of purification), and played physical games with obviously sexual connotations... |

| Kupalo Festival |

|

WEDDING. In Ukraine the traditional wedding was a well-planned ritual drama, in which the leading roles were played by the bride and bridegroom, called princess and prince, and the other clearly defined roles (matchmaker, groomsman, bridesmaids) by the couple's parents, relatives, and friends. The wedding combined the basic forms of folk art--the spoken word, song, dance, music, and visual art--into a harmonious whole. It was reminiscent of an ancient theatrical drama with chorus, whose spectators were also actors. The rituals date back to pre-Christian times (traces of matriarchy, the abduction of the bride) and were influenced extensively by medieval practices (ransoming the bride, simulating a military campaign, the fighting between two camps, addressing the guests as princes and boyars, and the church ceremony). The ceremony included traces of ancient customs, which had lost their original, mainly magical, significance and had become mere play. Gradually the church ceremony assumed the central role in the wedding. The traditional Ukrainian wedding usually took place in the early spring or the autumn and lasted several days... |

| Wedding |

|

HARVEST RITUALS. Folk rituals dating back to ancient times and marking the opening and closing of the harvest period. These ceremonies were characterized by a sequence of magical rituals that interacted with natural processes and phenomena. The spiritualization of nature was at the essence of these rites, which could influence critically the fate of the harvest. Zazhynky marked the commencement of harvesting and took place at the end of June or the beginning of July. In the morning, all the reapers went into the fields together. The master or village elder took off his hat, turned to the sun, and uttered a special incantation requesting the fields to surrender their harvest and to give the reapers sufficient strength with which to gather it in. Then, the mistress or a woman reputed to be lucky cut the first sheaf of grain, which was called voievoda. In the evening, the voievoda sheaf was brought to the master's house and was placed in the icon corner where it was to stand until the end of the harvesting. Obzhynky marked the end of the harvesting, usually at the end of July or the beginning of August, and was associated with an array of customs and rituals... |

| Harvest Rituals |

|

BURIAL RITES. The ancient burial rites of the Ukrainian people were based on various folk customs and beliefs. The body of the deceased was washed, dressed, and placed on a bench under a window, with the head towards icons and the feet towards the door. As long as the deceased remained in the house, all work ceased, except that required for the funeral. The house was not swept during the funeral proceedings. The body was carried to the grave feet first, and the mourners followed, to prevent the deceased from 'seeing' them. The coffin was knocked against the threshold three times so that the deceased might bid farewell to his or her home and not return. Kolyvo--cooked wheat or barley covered with honey--was carried in front of the coffin in the funeral procession and was always the first course of the funeral meal. The ritual was accompanied by wailing and lamentation. Following the requiem, the 'final embrace,' a formal leave-taking of the deceased, took place, after which the coffin was lowered into the grave, in a position so that the deceased faced the sunrise. Those people who were directly involved in the burial purified themselves by washing their hands and touching the stove before sitting down to dinner... |

| Burial Rites |

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries about Ukrainian folk customs and rituals were made possible by the financial support of the PETER SALYGA ENDOWMENT FUND at the CANADIAN INSTITUTE OF UKRAINIAN STUDIES (Edmonton, AB, Canada).

VI. UKRAINIAN TRADITIONAL FOLK BELIEFS, MYTHOLOGY, AND DEMONOLOGY

VI. UKRAINIAN TRADITIONAL FOLK BELIEFS, MYTHOLOGY, AND DEMONOLOGY

According to the earliest historical record of pre-Christian religious beliefs in Ukrainian territory (from 6th-century AD), the proto-Ukrainian tribes were monotheist. They believed in a god of lightning and thunder and sacrificed cattle and other animals to him. Through millennia of progressive development, a complex system of Ukrainian mythology, demonology, and folk beliefs developed that encompassed almost all events and objects of the external world, as they were seen to influence collective and individual destiny. The institution of Christianity did not completely destroy these traditional beliefs. Instead, mythological elements were combined with elements of Christianity, creating a 'dual faith.' The 'lower' mythology (that was older in origin than the pagan belief in 'higher' gods), involving ancestral-clan images and an animistic world view that populates nature with spirits, proved stable and survived until recent times. Learn more about Ukrainian traditional folk beliefs, mythology, and demonology by visiting the following entries:

|

FOLK BELIEFS. A fundamentally religious interpretation of the world that determines the conduct and the attitude of the common people towards the forces of nature and the events of ordinary life. These beliefs are passed on by tradition or spring from an animistic view of natural phenomena, spiritual life (eg, the souls of the dead), and inanimate objects, or from such psychic experiences as illusions, hallucinations, and dreams. Ukrainian folk beliefs encompass almost all events and objects of the external world, which are held to have a determining influence on individual destiny. There is a rich body of beliefs connected with the sun, moon, and stars. There are many different beliefs about atmospheric phenomena and about the actions of fire, water, earth, stones, plants, animals, and birds as well as man-made objects... |

| Folk beliefs |

|

MYTHOLOGY. A body of myths or stories dealing with the gods, demigods, and heroes of a given people. The earliest historical record of pre-Christian religious beliefs in Ukrainian territory belongs to the 6th-century Byzantine historian Procopius of Caesarea. According to him the Sclaveni and Antes were monotheist. They believed in a god of lightning and thunder and sacrificed cattle and other animals to him. Mykhailo Hrushevsky and other scholars assumed it was Svaroh. These peoples also venerated rivers, water nymphs, and other spirits, offered sacrifices to them, and foretold the future from the offerings. Two periods are distinguished in the evolution of eastern Slavic mythology: an earlier one, marked by Svaroh's supremacy, and a later one, dominated by Perun... |

| Mythology |

|

DEMONOLOGY IN UKRAINE. With the institution of Christianity in Ukraine and the official proscription of paganism at the end of the 10th century, elements of the unified pagan religion disappeared rapidly, and the names of the 'higher' gods (Perun, Dazhboh, Veles, Stryboh, Khors, and others) were preserved only in literature. The 'lower' mythology proved much more stable, however, and survived until recent times. This 'lower' mythology, involving ancestral-clan images and an animistic world view that populates nature with spirits, was older in origin than the pagan belief in 'higher' gods. The institution of Christianity did not completely destroy the belief in the 'lower' mythology. Instead, mythological elements were combined with elements of Christianity, creating a 'dual faith'... |

| Demonology |

|

MAGIC. A set system of notions, rituals, and invocations that are believed to have a mysterious mystical power to influence physical phenomena or natural events. Magic played an important role in the life of Ukrainians, particularly the peasantry. Not a step could be taken without it. It was used widely in medicine: shamans used spells and charms, often combined with rational practices, employing medicinal plants or psychotherapy. Water, fire, and eggs were held in the highest esteem by Ukrainian sorcerers. Magic was also an important part of calendric folk rituals tied to farming (sowing, harvesting, taking livestock to pasture) and family life (birth, wedding, and death)... |

| Magic |

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries dedicated to Ukrainian traditional folk beliefs, mythology, and demonology were made possible by a generous donation of the CANADIAN FOUNDATION FOR UKRAINIAN STUDIES.

VII. UKRAINIAN CHRISTMAS AND NEW YEAR TRADITIONS

VII. UKRAINIAN CHRISTMAS AND NEW YEAR TRADITIONS

The celebrations of Christmas, New Year, and Epiphany (Yordan) are part of the traditional winter festivities cycle. Their roots reach deep into the past to the ancient pre-Christian times. Christmas as the feast of Christ's birth was at first celebrated in the East on 6 January, together with the feast of Epiphany. Later, in the mid-4th century, it was established by the Roman Catholic church as a separate feast and was celebrated on 25 December according to the Julian calendar. With the introduction of Christianity into Ukraine in the 10th century Christmas was fused with the local pagan celebrations of the sun's return or the commencement of the agricultural year. In some areas the pre-Christian name of the feast--Koliada--has been preserved. The most interesting part of Ukrainian Christmas is Christmas Eve (Sviat-Vechir) with its wealth of ritual and magical acts aimed at ensuring a good harvest and a life of plenty. Dead ancestors and family members are believed to participate in the eve's celebration and are personified by a sheaf of wheat called did or didukh (grandsire). The 'holy supper' on Christmas Eve is a meal of 12 ritual meatless and milkless dishes. The order of the dishes and even the dishes themselves are not uniform everywhere, for every region adheres to its own tradition. A characteristic feature of Christmas is caroling (koliaduvannia), which expresses respect for the master of the house and his children and is sometimes accompanied by a puppet theater (vertep) or by Christmas carolers dressed up as vertep characters, by an individual dressed up as a goat (as part of the folk play Koza), and by a handmade star. The religious festival lasts three days and involves Christmas liturgies (particularly on the first day), caroling, visiting, and entertaining relatives and acquaintances. The Christmas theme has a very important place, more important than Easter, in Ukrainian painting, particularly church painting, and in poetry. The traditional folk Christmas 'holy supper' ritual and caroling are still observed, in a modified fashion, by Ukrainians in the diaspora. In Soviet Ukraine most Christmas rituals disappeared, but many of them have been revived in independent Ukraine, particularly in western oblasts... Learn more about the Ukrainian Christmas and New Year traditions by visiting the following entries:

|

CHRISTMAS. Although there were regional variations, the rituals of Christmas followed a set pattern in Ukraine in former days. Except for the preparation of the 'holy supper,' all work was halted during the day, and the head of the household saw to it that everything was in order and that the entire family was at home. Towards the evening the head of the house went to the threshing floor to get a bundle of hay and a sheaf of rye, barley, or buckwheat; with a prayer he brought them into the house, spread the hay, and placed the sheaf of grain (the didukh) in the place of honor (under the icons). Hay or straw was strewn under and on top of the table, which the housewife then covered with a tablecloth. Garlic was placed at the four corners of the table while iron objects--an ax and a plowshare (or the plow itself)--and a yoke, a horse collar, or pieces of harness, were placed under the table. A pot of kutia, a ritual dish made with wheat or barley grain and ground poppy seeds, was placed high up on the shelf in the corner of honor; the pot was topped with a loaf of bread (knysh) and a lighted candle. The evening meal was accompanied by a special ceremony. When the kutia was served, the head of the house took the first spoonful, opened the window or went out into the yard, sometimes with an ax in his hand, and invited the 'frost to eat kutia.' On re-entering the house, he threw the first spoonful to the ceiling: an adhesion of many grains signified a rich harvest and augured a good swarming of bees. At the evening meal fortunes were told. After the meal three spoonfuls of each dish were placed on a separate plate for the souls of the dead relatives and spoons were left for them... |

| Christmas |

"> ">

|

CAROLS. The custom of caroling is highly developed and widely practiced in Ukraine. There are two kinds of carols: koliadky and shchedrivky. The koliadky are festive, ritual songs sung at Christmas time, while the shchedrivky are sung on New Year's Eve. Both types of carols have retained traces of their ancient origin, particularly to the cult of the sun, of the ancestor worship, of nature worship, and of the faith in the magical power of words. The koliadky and shchedrivky depict scenes from farm life and express the desire for good harvests, prosperity, good fortune, and health. They are remarkable for their wealth of subject matter and motifs, which vary with the person who is addressed and praised in each carol. There are carols dedicated to the master of the house, the mistress of the house, the young bachelor, the girl, the daughter-in-law, the son-in-law, and so on. The most important aspect of carols is their wish-fulfilling power. By their age and content the carols can be divided into several groups: (1) the oldest carols, which deal with the creation of the universe in a pre-Christian, dualistic, mythological framework; (2) a later stratum describing life in the Princely era; (3) carols about daily life; and (4) recent koliadky and shchedrivky, which have a biblical theme--Christ's birth, the shepherds, the three wise men, Herod. The process of Christianization embraced the whole content of the koliadky and shchedrivky. In some carols the ancient agricultural themes are fused with more recent religious themes. As poetry koliadky and shchedrivky are remarkable for their artistic quality... |

| Carols |

_s.jpg)

|

KOZA. A traditional mimetic folk play that was acted out during the Christmas cycle by young men, who visited all the houses in a village. The Goat--a youth wearing an inverted sheepskin coat and a mask resembling a goat's head--entered a house, bowed to the head of the household, and performed a ritual dance to bring about an abundant harvest. The other youths sang an accompanying ditty: 'De Koza khodyt', tam zhyto rodyt', de Koza tup-tup, tam zhyta sim kup' (Where the Goat goes, there wheat grows; where the Goat stamps its feet, there are seven sheaves of wheat). A dramatization of a goat being pursued by hunters and wolves, killed, and gutted followed. At the singers' call 'Bud', Kozo, zhyva!' (Come alive, Goat!) the Goat rose from the dead and returned to its 'field,' which then came to life (as acted out by the chorus). The game ended with the Goat delivering a wish: 'Shchob ts'omu hospodariu i korovky buly nevrochlyvii i molochlyvii, i oves-samosii, i pshenytsia-sochevytsia' (May this farmer's cattle be unbedeviled and full of milk, and may his oats sow themselves and his wheat be of the best sort). In the Hutsul region the Goat was 'led around' by children, who 'sowed' grain kernels throughout the house; the Goat's ears were made of grain spikes. Occasionally, the Goat was accompanied by others disguised as the Old Man, the Gypsy, Malanka (the New Year's Eve maiden), the Bear, and other characters. The original purpose of Koza was the same as that of carols: to invoke a successful year for the peasant household... |

| Koza |

|

NEW YEAR. The first day of the yearly cycle, marked with religious and traditional festivities. Before its Christianization in 988, Kyivan Rus' followed the ancient Roman calendar, which began the year on 1 March. With Christianity came the Byzantine calendar, which began the new year on 1 September and followed a chronology which set the date of creation at 5508 BC. The common people, however, continued to use the Roman calendar. In the 14th and 15th centuries, under Polish and Lithuanian influence, the Julian calendar, which began the year on 1 January, was adopted in Ukraine. In Russia this change came only in 1700, under Peter I. The more accurate Gregorian calendar was adopted in Western Europe in 1582, but neither the Ukrainian people nor the church accepted this calendar. Today Ukrainians in and outside Ukraine celebrate the New Year twice: officially on 1 January, according to the Gregorian calendar, and unofficially on 14 January (1 January according to the Julian calendar). The New Year, particularly New Year's Eve, was celebrated with a rich repertoire of folk rituals. Their primary purpose was to secure a bountiful harvest and the family's health and happiness. The key rituals were the eating of kutia, children's caroling, the polaz (bringing cattle into the house), walking Malanka around the village, fortune-telling and forecasting the weather for the next year, and the symbolic sowing of wheat. According to popular superstition, on New Year's Eve domestic animals are able to speak in human language, and buried treasures burn with a blue flame... |

| New Year |

|

MALANKA. A Ukrainian folk feast on New Year's Eve corresponding to Saint Sylvester's Feast in the Latin calendar. The name originates from Saint Melaniia, whose day falls on 13 January (31 December OS). In central and eastern Ukraine the feast was also known as Shchedryi vechir (Generous Eve) or Shchedra kutia. Traditionally, Malanka (a bachelor dressed in women's clothing), with a dressed-up goat, gypsy, old man, old woman, Jew, and other characters and musicians, went from house to house in the village supposedly to put the households in order. But instead of bringing order Malanka played all kinds of pranks. In some locales young men and women brought a plow into the house and pretended to plow a field. The folk play was concluded with caroling. The Malanka traditions were most prevalent in the Dnipro region. They combine old agrarian themes with folk theater (the intermede and vertep). After the Revolution of 1917 the Malanka tradition declined in Soviet Ukraine, but it was revived in the early 1930s as part of the New Year celebrations. Today Ukrainians in and outside Ukraine celebrate Malanka as the traditional way of inaugurating the Julian-calendar New Year... |

| Malanka |

|

EPIPHANY (Ukrainian: Bohoiavlennia). A religious feast on January 6 (OS) or January 19 (NS), popularly called Vodokhreshchi (Blessing of Water) or Yordan (Jordan River), which completes the winter (Christmas-New Year) festivities cycle. Its Christian content is permeated with old agricultural rituals of diverse origins. The Eve of Epiphany is called 'the second Holy Eve' or 'Hungry Kutia'; in Podilia it is also called Shchedryi Vechir (Generous Eve). It calls for a more simple meal than on Christmas Eve but with kutia still as the main traditional dish. The principal ceremony of Epiphany traditionally consisted of the solemn outdoor blessing of waters, usually at a river or at a well, where a cross was erected out of blocks of ice (nowadays water is usually blessed inside the church). A procession was led to the place of ceremony. After the blessing of the water, everyone present drank the water and also took some home to be kept there for a whole year. On the second day of Epiphany (Day of Saint John the Baptist) the head of the household traditionally fed his cattle with bread, salt, and hay, which had been in the house since Christmas Eve, 'to last them till the new bread.' Following the feast of Epiphany, parish priests visit the parishioners' homes and bless them with the new holy water... |

| Epiphany (or Yordan) |

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries dealing with the Ukrainian Christmas and New Year traditions were made possible by the financial support of the SENIOR CITIZENS HOME OF TARAS H. SHEVCHENKO (WINDSOR) INC. FUND.

VIII. TRADITIONAL HANDICRAFTS OF THE UKRAINIAN PEOPLE

VIII. TRADITIONAL HANDICRAFTS OF THE UKRAINIAN PEOPLE

Crafts and small-scale manufacture of common articles of daily use, farm implements, clothing, home furnishings, and, in past centuries, arms as well were widely practiced in Ukraine from the earliest times. Crafts were highly developed in the ancient states on the northern Black Sea coast. At the beginning of the 1st millennium AD crafts began to be separated from farming and specialized, and there were two basic branches of craft manufacture--iron making and pottery. In the Princely era the urban crafts differed from the rural crafts in their more complex production process and the higher quality of their product. In the large cities there were close to 60 distinct crafts: specialized branches of metallurgy, blacksmithing, arms manufacturing, pottery, carpentry, weaving, linen and wool cloth making, and others. Crafts specializing in ornamental products such as clothes, church and palace decorations, icons, and jewelry were highly developed. The Mongol invasions caused the crafts to decline. The earliest revival of the crafts occurred in the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia, where in the second half of the 14th century and the first half of the 15th century guilds appeared in the cities and towns governed by Magdeburg law. The largest crafts center was Lviv, where by the second half of the 15th century there were already over 50 crafts and by the first half of the 17th century, 133 crafts. At the same time traditional folk handicrafts developed in village communities... Learn more about the traditional handicrafts of the Ukrainian people by visiting the following entries:

|

CRAFTS. With the decline of the barter economy crafts became separated from home manufacture, which served the needs of the producer and his/her neighbors, and became increasingly specialized. Crafts production was concentrated mostly in the cities and towns in the form of small enterprises. Usually products were made to order; sometimes they were made for the market. There was hardly any division of labor in the craft shops, except for partial help from family members, journeymen, or apprentices. The craftsman was the owner of the shop and the means of production. Alone or with a journeyman he was an independent producer capable of manufacturing the product from beginning to end. His craft was his basic occupation and means of livelihood. At the peak of their development the craftsmen formed a relatively closed social group of the burgher estate with a distinct way of life and civil status and special rights and duties. In these respects crafts differ from cottage industries, which are usually only supplementary occupations undertaken, for example, during a season free of farm work... |

| Crafts |

|

CERAMICS and Pottery. Objects made of natural clays or clays mixed with mineral additives and fired to a hardened state. The ceramics made on the territory of Ukraine from the earliest times to the present reveal a highly developed artistic and technical culture, originality, and creativity. The development of ceramics has been facilitated by the existence of large deposits of various clays, particularly kaolin (china clay). The history of Ukrainian ceramics begins in the Neolithic Period, with the ceramics of the Trypilian culture. Their high technical and artistic level equals that seen in artifacts of the Aegean culture. The development of Ukrainian ceramics was also influenced by the ceramics of the Hellenic colonies on the Black Sea coast, beginning in the 8th and 7th century BC. Ceramics of the so-called Slavic era, which began in the 2nd century AD, were more modest, and only in the Princely era (9th-13th century) did the production of ceramics achieve a high technical level and a variety of artistic forms, while growing into a large industry... |

| Ceramics |

|

WEAVING. Weaving has been practiced in Ukraine for many centuries. Using flax, hemp, or woolen thread, weavers have produced various articles of folk dress, towels, kilims, blankets, tablecloths, sheets, and covers. The colors, ornamentation, and even the techniques of weaving varied from region to region. By the 14th century weaving had developed into a cottage industry. Weavers' guilds modeled on Western European examples were founded in Sambir (1376), Lviv, and elsewhere in Galicia. Later, artistic textiles and kilims were manufactured by small enterprises established by magnates in Brody (1641), Lviv, Nemyriv, Korsun, and other towns. In 17th-century Left-Bank Ukraine the Cossack starshyna established similar enterprises to make decorative furnishings on order for the nobility and churches, using imported silk and gold thread. Eventually such thread was manufactured in Ukraine. Weaving manufactories flourished from the mid-17th to the mid-19th century. The town of Krolevets became one of the largest centers of artistic folk weaving... |

| Weaving |

|

EMBROIDERY. Archeological discoveries in Ukraine indicate that embroidery has existed there since prehistoric times. Embroideries are found on drawings and on the oldest pieces of extant cloth (eg, the veil from the Church of the Tithes, destroyed in 1240). Cloth embroidery was first inspired by faith in the power of protective symbols and later by esthetic motives. Symbolic designs were incorporated into the woven cloth by means of a weaving shuttle or a needle. These symbols formed the basis of ornamentation for both cloth and Easter eggs. Under the influence of Byzantine art a new branch of embroidery--church embroidery--was developed in the Middle Ages. In the course of time and under the influence of new artistic styles, folk embroidery and church embroidery became more differentiated. Centers of church embroidery developed in the monasteries, while certain cities became centers for the embroidery trade, which produced cloth for the Cossack starshyna and the nobility. The later artistic styles did not influence folk embroidery as much... |

| Embroidery |

|

KILIM WEAVING. The term 'kilim' is of Turkic origin and denotes an ornamented woven fabric used to cover floors or to adorn walls. The earliest references to kilims date back to the chronicles of Kyivan Rus' and link them to burial rites. The princes used kilims also as chair covers. Nothing definite can be said about kilim weaving in Ukraine before the 16th century. The earlier kilims belonging to the ruling class most likely had been imported. Kilim production in Volhynia in the 16th century is well documented. There are many 17th-century references to both locally produced and imported kilims. By the 18th century, kilim weaving was widespread: in Right-Bank Ukraine the mills owned by the Czartoryski and Potocki families, and in Left-Bank Ukraine Col Pavlo Polubotok's mill, were well known. Although kilim weaving may have been taken up by peasants much earlier, in the 18th century it became widespread among them. Monks and town craftsmen also engaged in weaving. The industry grew rapidly at the end of the 18th century and in the first half of the 19th century... |