Jews

Jews (Ukrainian: жиди, юдеї, євреї; zhydy, iudei, ievreï). Jews first settled on Ukrainian territories in the 4th century BC in the Crimea and among the Greek colonies on the northeast coast of the Black Sea (see Ancient states on the northern Black Sea coast). From there they migrated to the valleys of the three major rivers—the Volga River, Don River, and Dnipro River—where they maintained active economic and diplomatic relations with Byzantium, Persia, and the Khazar kaganate. The latter empire consisted of Turkic tribes that converted to Judaism in about 740 AD. In the aftermath of Khazaria's conquest in 964 by the Kyivan prince Sviatoslav I Ihorovych, Khazarian Jews settled in Kyiv, the Crimea (see Karaites), and Caucasia.

Throughout the 11th and 12th centuries Khazarian Jews steadily migrated northwards. In Kyivan Rus’ the Jewish population developed a distinct presence. In Kyiv they settled in their own district called Zhydove, the entrance to which was called the Zhydivski vorota (Jewish gate). Jews fleeing the Crusaders came to Ukraine as well, and the first western-European Jews began to arrive from Germany, probably in the 11th century.

The Kyivan princes Iziaslav Mstyslavych and Sviatopolk II Iziaslavych, Prince Danylo Romanovych of Galicia-Volhynia, and the Volhynian prince Volodymyr Vasylkovych were well disposed to their Jewish subjects and assisted their activities in trade and finance. Jews were also appointed to administrative and financial posts. However, as in other parts of Europe, this benevolent treatment was not consistent. During the Kyiv Uprising of 1113 the Zhydove district was ransacked, and during the rule of Volodymyr Monomakh Jews were expelled from Kyiv. The Mongol conquest of the Crimea and of Kyivan Rus’ strengthened commercial relations, and brought peace and prosperity to the Jewish community up to the time of the Tatar-Lithuanian War (1396–99).

The expulsion of the Jews from the states and cities of Western and Central Europe in the 13th–15th centuries led Jews to flee eastward, to Austria, Hungary, Bohemia, Moravia, Poland, and the Ottoman Empire. By 1500, Jews living in Ukrainian lands under Polish rule could be found in 23 towns and constituted one-third of all Jews in the Polish kingdom. The central European Jews (ashkenazim) spoke Yiddish (a German dialect), wore distinctive dress, and lived apart from the local population, either in separate districts or ghettos of cities, or in small, predominantly Jewish, settlements (shtetl). They were usually poorer than the earliest Jewish immigrants to Ukraine. Barred from owning land and from the professions, the majority of Jews were engaged in modest occupations, as artisans and in petty trade. Protected by the Polish monarchs against hostile nobles and urban dwellers, Jews were directly subordinate to the king, paying a separate tax for which they were collectively responsible. In return, royal decrees (dating back as early as 1264) allowed the Jews to govern themselves. In 1495 King Alexander Jagiellończyk established autonomous local governments (see Kahal), with jurisdiction over schools, welfare, the lower judiciary, and religious affairs. From the mid-16th century to 1763 the central institution of Jewish life in the Polish Kingdom was the Council of the Four Lands (Great Poland, ‘Little Poland,’ Chervona Rus’ [Galicia], and Volhynia). The council met semiannually (later irregularly), with the site alternating between Jarosław and Lublin, to apportion the responsibility for taxes and decide on matters of concern to the Jewish community.

In the late 15th century Jews from Poland and Germany began arriving in Ukrainian territories under Lithuanian rule (especially the Kyiv region and Podilia). Kyiv became a famous center of Jewish religious education. This period was also one of suffering for both the indigenous and the Jewish populations because of the Tatar raids. In 1482 many Jews were seized by the Tatars and sold into slavery in the Crimea.

The largest migration of Jews to Ukrainian territories took place in the last quarter of the 16th century. Some came from other parts of Poland and Lithuania to settle the newly opened areas; others from as far as Italy and Germany. In 1569, with the creation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (see Union of Lublin) and the transfer of Ukraine from Lithuanian to Polish administration, vast areas of Ukraine were opened to colonization and to commercial agricultural development for trade with Western Europe. Between 1569 and 1648 the number of Jews in Ukraine increased from about 4,000 to nearly 51,325, dispersed among 115 towns and settlements in the Kyiv voivodeship, Podilia voivodeship, Volhynia voivodeship, and Bratslav voivodeship. If the older Jewish community in the Rus’ voivodeship and Belz voivodeship is included, at the turn of the century there were 120,000 Jews in Ukrainian territories, out of an estimated total population of 2 to 5 million. This rapid increase was a result not only of migration but also of natural population growth.

Jews began taking advantage of the new professional and economic opportunities in the frontier territories of Ukraine. As Polish and Lithuanian nobles accumulated more land, Jews came to act as their middlemen, providing indispensable services to the absentee and local lords as leaseholders of large estates, tax collectors (see Tax farming), estate stewards (with the right to administer justice, including the death penalty), business agents, and operators and managers of inns, dairies, mills, lumber yards, and distilleries. In trade, they supplanted Armenians and competed with urban Ukrainians. Jews came to be perceived as the immediate overlords of the peasantry and the most important competitors to the urban Christian Orthodox population.

The situation of the Jewish population became increasingly vulnerable in the early 17th century. Dissatisfaction with the difficult conditions on the part of the enserfed peasantry, the Cossacks, and urban Orthodox Ukrainians led to the 1648 uprising under Bohdan Khmelnytsky (see Cossack-Polish War). Polish landowners, Catholics, and Jews were the main victims of the uprising. In many cities, particularly in the Podilia and Volhynia regions and Left-Bank Ukraine, the Jewish population was decimated. Jewish eyewitness chroniclers (eg, Nathan Hanover) estimate the figure of casualties between 100,000 and 120,000. In light of the size of the estimated Jewish population in Ukraine in 1648 (51,325) this figure reflects rather the trauma of the experience and not the actual numbers. Nonetheless Jews, perceived as representatives of the Polish landlords, suffered greatly during the uprising. To escape persecution, some Jews converted to Christianity.

The status of Jews was very different in the Russian-dominated Hetman state. The Russian government was opposed to Jewish immigration and, beginning with Peter I, forbade Jews from settling in Left-Bank Ukraine. Nevertheless, because the economic value of Jewish settlers was recognized by officials of the Hetmanate, the decrees issued by Saint Petersburg for the expulsion of Jews from Left-Bank Ukraine were not always enforced, and several petitions were addressed to Saint Petersburg requesting permission to allow Jews in. Most Jews, however, lived in Right-Bank Ukraine, which remained under Polish control until 1772.

The economic hardship of the peasantry and the intensified national and religious oppression by Poland in these areas caused popular unrest that came to be directed also against Jews. This unrest was manifested in the Haidamaka uprisings, and especially the Koliivshchyna rebellion of 1768, when 50,000–60,000 Jews perished out of a total Jewish population of about 300,000 in Right-Bank Ukraine. Nevertheless, Jewish immigration to Ukraine continued throughout the 18th century, and while most Jews lived in poverty, some began to acquire great wealth.

After the partition of Poland in the late 18th century, the presence of 900,000 Jews on what was now Russian imperial territory forced the Russian government to abandon its previous policy of exclusion of Jews from Russia proper. In 1772 (and 1791, 1804, 1835) the government established a territorial region called the Pale of Settlement beyond which Jewish settlement was prohibited. In Ukraine this area included almost all the former Polish-controlled territories; the Left-Bank Chernihiv gubernia and Poltava gubernia, except for the crown hamlets; New Russia gubernia; Kyiv gubernia, but not the city of Kyiv; and Bessarabia (1812). The Pale existed, with some special criteria permitting individual Jews to live outside it, until 1915.

During the reign of Alexander I (1801–25) the position of Jews initially improved as restrictions on their movement and enrollment in schools were eased and official anti-Semitic propaganda abated. Economically, Jews prospered in Southern Ukraine, where they played a major role in the grain trade; they acquired an especially strong presence in such commercial centers as Odesa, Kremenchuk, and Berdychiv. In 1817 Jews owned 30 percent of the factories in Russian-ruled Ukraine. Towards the end of Alexander's rule, however, state-sponsored conversion attempts and expulsions from certain areas were encouraged.

Under Nicholas I (1825–55) official persecution of the Jews increased dramatically. Of the 1,200 laws affecting Jews between 1649 and 1881, more than half were instituted during his reign. Among these provisions were compulsory military service for Jews (1827), including the conscription of children; expulsions from cities (Kyiv, Kherson, and Sevastopol); abolition of the kahal (1844); banning of the public use of Hebrew and Yiddish; aggressive conversion measures; and further travel and settlement restrictions (1835). In 1844 a decree was issued that created new Jewish schools similar to the parish and district schools and that aimed to assimilate the Jews.

Jews benefited from the brief period of liberalism that initially characterized the reign of Alexander II (1855–81). With the rise of the Jewish emancipation movement a few restrictions were loosened: some Jews—among them merchants of the first guild (1859), university graduates (1861), and various categories of artisans and tradesmen (1865)—were granted freedom of movement; and conscription of Jews into the army was placed on the same basis as for other subjects of the empire (1856), which included the abolition of the conscription of children. By 1872 Jews were actively engaged in the major industries in Ukraine: they comprised 90 percent of all those occupied in distilling and 32 percent in the sugar industry. But with the Odesa pogrom in 1871, the momentum for reform was quickly reversed, especially after the assassination of the tsar, and new laws restricting Jewish economic activity were introduced. In 1873, the rabbinical college in Zhytomyr was transformed by the authorities into a secular school.

The reign of the tsar's successors, Alexander III (1881–96) and Nicholas II (1896–1917), ushered in an era of state-supported pogroms (1881–2, 1903, 1905), charges of ritual murder in the Beilis affair (1913), expulsions from Kyiv (1886) and Moscow (1891), and stricter segregation of the Jewish population with in the Pale of Settlement (1882). Wide-scale pogroms took place in October 1905, when in one month 690 pogroms were carried out in 28 gubernias (of which 329 pogroms were in Chernihiv gubernia alone). Many of these outbursts were encouraged by the anti-Semitic Black Hundreds movement.

The government limited educational opportunities in 1887 and again in 1907 by placing a quota on Jews to be admitted to secondary schools and universities: 10 percent within the Pale of Setllement, 3 percent in Moscow and Saint Petersburg, and 5 percent in the rest of the empire. Jews could be admitted to the bar only with permission of the minister of justice (1887), and they could not vote in district zemstvo assembly elections (1890), even though they were obliged to pay zemstvo taxes. Economically, Jews were deprived of an important source of livelihood when the government forbade them to acquire property outside towns or large villages (1882), forcing them into the cities, and again (1894) when the state declared a monopoly on the sale of spirits, refusing Jews licences to sell spirits (see Propination). The desperate economic position of Jews in the Pale was reflected in the fact that 30 percent had to be supported by philanthropic relief. In essence, the Jews never achieved or were never granted emancipation under tsarist Russian rule.

The reaction to these repressive measures and activities was a dramatic increase in Jewish emigration to North America, increased support for the Zionist movement (the largest Jewish political movement by 1917), and active participation in all-Russian revolutionary or Jewish socialist political parties. Among the latter were the Bund and the smaller Jewish Socialist Labor party, Zionist Socialist Labor party, and Poale Zion.

During the First World War more than 500,000 Jews were deported from the military zones, and as the Russian army defeats increased, so the position of the Jews deteriorated. They were accused of being spies and traitors and of undermining the regime.

In Austria-Hungary, Jews did not receive rights equal to those of the general population until 1868. Until then, their rights were limited by the Josephine patents (see Joseph II), which sought to assimilate Jews and to involve them in agriculture. When Galicia (1772) and Bukovyna (1774) were incorporated into the Austro-Hungarian Empire, most Jews in Galicia were concentrated in the eastern part of this crown land. They made up about 11 percent of the population of Galicia both in 1869 (575,433) and in 1900 (811,183). Sixty percent of Jews were engaged in trade and commerce in an area where 75 percent of the population (and 94 percent of Ukrainians) earned its livelihood from agriculture and forestry. Jews formed an absolute majority in many important trading centers, such as Brody on the Russian border. Jews figured prominently as officials attached to the estates (stewards, overseers, labor recruiters); as storekeepers, leaseholders of Polish estates, and tavernkeepers; as officials in local government; and in the working class (as workers in the petroleum industry centered in the Drohobych-Boryslav Industrial Region).

Only about 60 percent of eastern Galicia's Jews lived in cities and towns. Jews in rural areas represented a sizable portion of Galicia's Jewish population, and they were an anomaly in comparison to Jewish demographic patterns elsewhere. Both in terms of their numbers and because of their precarious position as middlemen between lord and peasant, rural Jews were often the scapegoats for dissatisfaction and resentment. Many among the non-Jewish population shared a hostile view of Jews as exploiters and servants of the Polish nobility and landowners, even though the vast majority of Jews lived in poverty, like their Ukrainian neighbors. In contrast to conditions in the Russian Empire, however, there were no pogroms; rather, the social and economic character of this antagonism was expressed in political and economic competition. As a vulnerable minority, Jews in Galicia usually voted with the ruling Polish nation, and throughout the second half of the 19th century Poles and Jews worked closely during the elections to parliament. After universal male suffrage was proclaimed in 1907, some Jews (especially supporters of the Zionist movement) allied themselves with Ukrainian political parties.

The collapse of tsarism in March 1917 (see February Revolution of 1917) soon brought emancipation for the Jews in the Russian Empire. On 20 March the Provisional Government declared that Jews were now equal citizens; they were not, however, granted national minority status or autonomy.

In Ukraine, the Central Rada established in March 1917 decided in late July to invite the minority nationalities (Russians, Poles, and Jews) to join its ranks. As a result, 50 Jews, from all the major parties, joined the Central Rada and 5 joined the Little Rada. The Jewish parties, gathered under the Jewish National Council, were also represented in the General Secretariat of the Central Rada (later the Council of National Ministers of the Ukrainian National Republic). Moisei Rafes, a Bundist, took on the post of general controller. Within the secretariat of nationalities, departments were set up for each minority and Moishe Zilberfarb, of the United Jewish Socialist Workers’ party, was appointed under secretary for Jewish affairs. He became general secretary for Jewish affairs, with ministerial ranking, on the formation of the Ukrainian National Republic (20 November 1917), and then minister for Jewish affairs when the proclamation of Ukrainian independence was issued (25 January 1918). Responsibility for Jewish affairs under the Central Rada thus passed from a department (undersecretariat) to a secretariat and then to a ministry. An advisory council representing the main Jewish parties was formed on 10 October 1917 and the Provisional National Council of the Jews of Ukraine convened in November 1918. Yiddish was one of the languages used by the Central Rada on its official currency and in proclamations, and the law on national-personal autonomy gave non-Ukrainian nationalities the right to manage their national life independently. However, during the regime of Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky (see Hetman government), this law was rescinded (9 July 1918) and the Ministry of Jewish Affairs abolished.

Under the Directory of the Ukrainian National Republic, the Ministry of Jewish Affairs (headed at first by Abraham Revusky) was re-established, and the law on national-personal autonomy was re-enacted. From April 1919, as the Directory was forced to move constantly westwards, the minister of Jewish affairs was Pinkhas Krasny. Other Jews who occupied prominent positions in the Central Rada or Directory governments were Solomon Goldelman, a deputy minister of trade and industry and of labor, and Arnold Margolin, a member of the Ukrainian Party of Socialists-Federalists who was deputy minister of foreign affairs and a diplomatic representative in London and at the Paris Peace Conference talks. Several prominent Zionists also supported Ukrainian autonomy, including Vladimir Zhabotinsky and Joseph B. Schechtman.

The Central Rada government was the first in history to grant Jews autonomy (see National minorities), and its relationship with Jewish political parties was generally amicable. All Jewish parties in the Central Rada voted for the creation of the Ukrainian National Republic and, because they were categorically opposed to the Bolsheviks, saw the Republic as the only remaining parliamentary democracy. The subsequent declaration of independence, however, was opposed by the Bund, and the other Jewish parties, including the Zionists, abstained from voting. In general, the mainstream Jewish public did not respond positively to the Central Rada and Jews preferred a united all-Russian government to better represent the interests of the Jewish minority. Neither was there full confidence in the Ukrainian government's ability or willingness to halt the spread of pogroms in Ukraine and to organize a strong military presence.

The scale of the pogroms during the struggle for independence (1917–20) in Ukraine was devastating for the Jewish population. The Whites (see Anton Denikin), peasant bands, otamans, and some units of the Army of the Ukrainian National Republic, having regarded Jews as pro-Bolshevik, all took part in these atrocities, as did the anarchists (see Nestor Makhno) and the Red Army. However, just before the formation of the Directory of the Ukrainian National Republic, elections to the Jewish communal councils indicated that of the 270,497 votes cast, 66 percent were for non-socialist parties (Orthodox and Zionist), while 34 percent voted for socialist party representatives.

The government and high command of the Army of the Ukrainian National Republic tried to combat the instigators of the pogroms. Orders were issued imposing courts-martial for pogromists and some executions were carried out. The government assisted pogrom survivors and co-operated with both the Jewish community and foreign representatives in investigations of the pogroms.

In Galicia, Jews were neutral in the Polish-Ukrainian conflict (see Ukrainian-Polish War in Galicia, 1918–19) but later the Jewish National Council in Stanyslaviv supported the Western Ukrainian National Republic government. They were granted equality and national rights, including permission to create their own police units. Some Jews served in the ranks of the Ukrainian Galician Army (see Jewish Battalion of the Ukrainian Galician Army).

The consolidation of Bolshevik rule brought the Jewish community both hardships and opportunities. Under War Communism (1918–21), when free commerce was banned and private businesses nationalized, Jews suffered great economic setbacks. Moreover, the Bolsheviks seemed determined to destroy the last vestiges of organized Jewish life. In April 1919 they abolished most community organizations. As part of their general antireligious propaganda they also closed down many synagogues and outlawed religious and Hebrew education. In Ukraine the Bolsheviks pursued a vigorous anti-Yiddish policy aimed at assimilating Jews; eg, the number of Yiddish books published declined from 274 in 1919 to 40 in 1923.

At the same time, formal and informal restrictions against Jewish participation in government and administration were abolished, especially for those who chose the path of assimilation. Special Jewish sections (the so-called yevsektsii) were formed within the Communist Party to facilitate Jewish participation, and it was often these groups that most strongly attacked the Zionist and traditional Jewish parties. Individual Jews benefited from the pro-Russian and pro-urban orientation of the Party, and many became part of the system, especially in education, the economy, and the middle echelons of the Party administration and government. Although only one-half of 1 percent of the total Jewish population joined the Bolshevik party, they constituted a large percentage of all Bolsheviks in Ukraine, in 1922 approx 13.6 percent of the Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine (CP[B]U). Fully 15.5 percent of the delegates to the 5th and 7th All-Ukrainian Congress of Soviets in 1921 and 1922 were of Jewish origin.

In an effort to consolidate the regime and broaden its support among the non-Russian nations, the Bolsheviks instituted a number of important changes in 1923. As a solution to the ‘nationalities problem’ the policy of indigenization was adopted. This policy encouraged the use of national languages and the recruitment of non-Russians into the Party, education, and the government. It is difficult to judge what effect the Ukrainian version of indigenization, Ukrainization, had on Ukraine's Jewish population. Since only 0.9 percent of all Ukrainian Jews (in 1926) declared their mother tongue to be Ukrainian, the introduction of Ukrainian as the official language certainly limited their opportunities in the Party, government, and scholarship. Moreover, the active recruitment of Ukrainians meant that the Jewish proportion would decline in these sectors. In 1923 Jews constituted 47.4 percent of students at higher educational institutions, but in 1929, only 23.3 percent, and their percentage in the CP(B)U fell from 13.6 in 1923 to 11.2 in 1926. Yet, in a speech to the 15th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolshevik) (CP[B]) in December 1927, Grigorii Ordzhonikidze, the head of the Central Control Commission of the Party, reported that Jews still constituted 22.6 percent of the governmental machinery in Ukraine and 30.3 percent in the city of Kyiv. The first secretary of the Central Committee of the CP(B)U from 1925 to 1926, Lazar Kaganovich, was of Jewish descent. In the end, Ukrainization was only a partial success, and it was finally abandoned in 1933 in favor of strict Russification.

Indigenization brought obvious benefits to the Jews as well. Jewish culture flourished in Ukraine, and several Yiddish theaters, institutes, periodical publications, and schools were established. Soviets in which the official language was Yiddish were established to administer the Jewish population: there were 117 such Soviets in 1926 and 156 by 1931. Moreover, Yiddish-language courts were set up, and the government offered a variety of services in Yiddish.

The New Economic Policy (NEP), which was introduced in 1921 to allow for some measure of private capitalist activity, was another significant development for the Jewish community. Many Jewish artisans re-established their private shops and at least 13 percent of all Ukrainian Jews became involved in commerce (1926). According to the census of 1926, fully 78.5 percent of all private factories in Ukraine under NEP were Jewish owned. This situation was short-lived. In the second half of the 1920s the Soviet authorities increasingly cut back on private capitalism, and NEP was for all practical purposes stopped by 1930.

In the 1920s the Soviet regime placed a major emphasis on changing the traditional social and economic structure of Jewish life, primarily by encouraging Jews to become engaged in agriculture. Jewish agricultural colonies had existed in Ukraine, especially Southern Ukraine, from the late 18th century. In 1924 the Soviet government setup two official bodies to promote Jewish rural settlement; they were assisted by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, which provided funds and machinery. From 69,000 in 1926, the number of Jewish farmers in the Ukrainian SSR increased to 172,000 in 1931; of these, 37,000 lived on colonies established under Soviet rule. One of the goals of some Jewish community leaders was the establishment of a Jewish territorial unit—an autonomous oblast or even Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic—on Ukrainian territory. As a first step, three Jewish raions were established: Kalinindorf (in Kherson okruha), founded in 1927; Novozlatopil (Zaporizhia okruha), in 1929; and Stalindorf (Kryvyi Rih okruha), in 1930. Eventually this plan was abandoned, at least partly because of the opposition of Ukrainian government leaders who feared the truncation of their republic; instead, in 1934 the Birobidzhan Jewish Autonomous oblast was established in the Far East. In the second half of the 1930s, most Jews left these agricultural colonies, either for Birobidzhan or for the cities.

The end of indigenization brought an end to the renaissance of organized Jewish life in the USSR. The Yiddish-language governmental institutions, the yevsektsii, the Yiddish writers' organizations, and many major cultural and scholarly institutions (eg, the Institute of Jewish Culture of the All-Ukrainian Academy of Sciences in Kyiv) were closed down, and the formal support given by the regime to Jewish developments was replaced by a growing official anti-Semitism. Many Jewish activists fell victims to the Stalinist terror of the 1930s.

In Western Ukraine during the interwar period strong economic competition from Ukrainian co-operatives and from private commercial and industrial firms eroded the economic base of Jewish life in Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Romania. The Polish government, and such Polish anti-Semitic groups as Rozwój, initiated anti-Jewish measures and activities. Despite the perception of economic antagonism between Jews and Ukrainians, there was some political co-operation: eg, in the 1922 and 1928 elections to the Polish Sejm, when Ukrainian and Jewish parties joined the coalition Bloc of National Minorities, and in the elections to the Czechoslovak and Romanian parliaments. Repressive Polish measures against Ukrainians and the co-operation of some Jewish leaders with the Polish government led to resentment of the Jews.

The first Soviet occupation of Western Ukraine (1939–41) followed the pattern already established in the USSR. On the one hand, Jewish national and cultural rights were limited, traditional institutions were abolished, and the economy was restructured and nationalized, bringing great hardships to artisans and merchants. On the other, individual Jews were given better opportunities as the official quotas, limiting their access to education and the professions, were abolished. Overall, many Jews welcomed the Soviet occupation, as it brought an end to the official anti-Semitism of the Polish regime and staved off the threat of Nazi occupation.

The German occupation of Ukraine during the Second World War—and, indeed, the entire war period—was a tragedy for Ukrainian Jews (see Holocaust). Within the enlarged 1941 boundaries of the Soviet Union, 2.5 of the 4.8 million Jews were killed. In Western Ukraine only 2 percent (17,000) of the entire Jewish population survived. The destruction of Jews began in fall 1941, initially in central Ukraine and then in Western Ukraine. In Kyiv alone, 35,000–70,000 Jews were murdered at Babyn Yar. Mass murder of Jews was carried out throughout Ukraine in 1942–4. Apart from the involvement of individuals and some organized auxiliary units, the Ukrainian population did not take part in these genocidal actions. Despite the penalty of death for aiding Jews, a number of Ukrainians, among them Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky, tried to save Jews.

The Jewish population suffered severe discrimination in the postwar years. The crackdown on Jewish community life intensified as the teaching of Hebrew was prohibited, the Yiddish theater was abolished, Yiddish publications were suspended, hundreds of Jewish leaders were arrested (1948), and Yiddish writers were imprisoned. Twenty-four of the more prominent leaders and writers in the USSR were executed after a secret trial in August 1952. In 1953 Joseph Stalin's persecutions came to a head with the so-called doctors' plot, in which nine doctors, six of them Jewish, were accused of conspiring with Western powers to poison Soviet leaders. Thousands of Jews were removed from official posts, particularly from the armed forces and security services, and their role in the Communist Party was reduced. In higher educational institutions quotas were imposed on the numbers of Jewish students admitted.

After Stalin's death the situation for individual Jews improved somewhat, but the assimilatory campaign and repression of Jewish culture and religion continued. Anti-Semitism in the guise of ‘anti-Zionism’ became part of Soviet internal and foreign policy. Soviet Ukrainian educational institutions were also used in this campaign; for example, the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR in 1963 published T. Kichko's anti-Semitic pamphlet, Judaism without Embellishment. Only about 60 synagogues survived into the 1980s in the USSR, and, of these, more than half were in Georgia.

After the 1967 Six-Day War in the Middle East and the emergence of the dissident movement in the Soviet Union, a strong Jewish emigration movement arose. In the 1970s there was a massive emigration of Jews from Ukraine to the West, including Israel and North America. Between 1970 and 1980, 250,000 Soviet citizens emigrated on Israeli visas. By 1980 severe restrictions were placed on Jewish emigration; it is estimated that in 1981 alone, approx 40,000 were refused permission to emigrate.

Ukrainian dissidents, including Ivan Dziuba, Sviatoslav Karavansky, Yevhen Sverstiuk, Viacheslav Chornovil, Leonid Pliushch, and Petro Grigorenko (Hryhorenko), have worked with Jewish activists (eg. E. Kuznetsov, A. Shifrin, A. Radygin, and Yosyf Zisels) in advocating Jewish-Ukrainian co-operation. Ukraïns’kyi visnyk, the Ukrainian samvydav journal, continuously reported on the persecution of Jewish activists.

In 1979 Ukrainian Jewish émigrés in Israel formed the Public Committee for Jewish-Ukrainian Cooperation, which in 1981 became the Society of Jewish-Ukrainian Relations, headed by Ya. Suslensky. Even earlier, in the 1950s, a commission of Jewish-Ukrainian affairs was established at the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in New York, and in 1953 the Association to Perpetuate the Memory of Ukrainian Jews was formed in New York, headed by Mendl Osherowitch.

Demography. At the end of the 19th century there were approx 3 million Jews living in ethnographic Ukrainian territories (see Table 1). Ukraine at that time had the highest concentration of Jews in the world, with some 30 percent of the total world population of Jewry (1.3 million Jews lived in Poland and 1.2 million in Lithuania and Belarus). In the eight Ukrainian gubernias of Russian-ruled Ukraine in 1897, 43.3 percent of all Jews worked in commerce, 32.2 in crafts and industry, 7.3 in private services, 5.8 in public services (including the liberal professions), 3.7 in communication, 2.9 in agriculture, and 4.8 in no permanent occupation.

Almost 60 percent of Ukrainian Jews lived in cities and constituted one-third of the urban population of the country. Because of their confinement to the Pale of Settlement, the Dnipro River served as a major demographic demarcation line. In Western Ukraine and Right-Bank Ukraine, Jews made up 10–15 percent of the population, but in Left-Bank Ukraine, only 4–6 percent. In most cities of Western and Right-Bank Ukraine they constituted a relative majority (40 percent on average), while they formed an absolute majority in such cities as Berdychiv (78 percent), Uman (58 percent), and Bila Tserkva (53 percent).

The First World War and the subsequent upheavals of 1917–21 in the central and western lands led to a significant decrease in the Jewish population as a result of casualties and a sizable emigration. The abolition of the Pale of Settlement enabled Jews to move to other parts of the old Russian Empire as well as to eastern Ukraine and the Kuban region. As a result, the Jewish population in Ukrainian territories decreased from 8.3 percent of the total population in 1897 to 5.5 percent in 1926. (Jewish population distribution is given in Table 2.)

Overall, the greatest percentage decreases occurred in Right-Bank Ukraine, while the greatest increases occurred in Slobidska Ukraine (particularly in Kharkiv). The distribution of Jewish population by geographic region for 1897 and 1926 is given in Table 3.

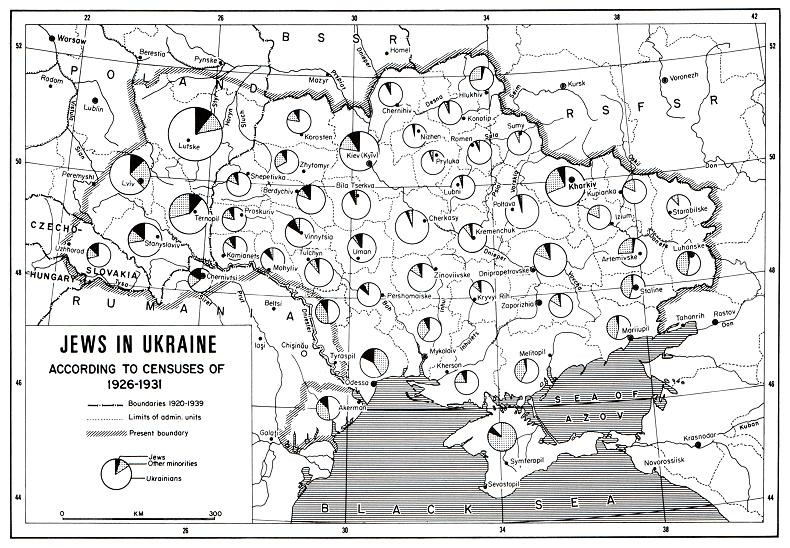

Demographic data for the Ukrainian SSR in 1926 (see map: Jews in Ukraine in 1926–31) illustrate the high rates of Jewish urbanization: 26 percent of the total Jewish population lived in villages, 51.6 percent lived in cities of 100,000 or less, and 22.2 percent lived in cities with a population of more than 100,000. Moreover, the concentration of Jews in medium- and large-sized cities, a process that began in the 19th century, continued. Between 1897 and 1926, the number of Jews decreased by 33 percent in villages and by 22 percent in towns of less than 20,000; meanwhile, their number increased by 7 percent in cities of 20,000 to 100,000 and by 106 percent in cities of over 100,000. In 1897, 27.4 percent of Ukraine's urban population was Jewish; in 1926, 22.8 percent.

The cities with the largest populations of Jews in 1926 (1897 figures in parentheses) were Odesa, 154,000 or 36.5 percent of the total population (140,000, 34.8 percent); Kyiv, 140,500 or 27.3 percent (31,800, 12.8); Kharkiv, 81,500 or 19.5 percent (11,000, 6.3); and Dnipropetrovsk, 62,000 or 26.7 percent (40,000, 35.5). In 1931 Lviv's Jewish population numbered 98,000 or 31.9 percent (in 1900 the respective figures were 44,300 and 26.5), and in Chernivtsi, 42,600 or 37.9 percent (21,600 or 32.8 percent). Before the First World War, Odesa had the third-largest Jewish population in the world after New York and Warsaw. According to the 1926 Soviet Ukrainian census, the distribution of the Jews by occupation was as follows: 20.6 percent in arts and crafts, 20.6 in public services (administrative work), 15.3 workers, 13.3 in commerce, 9.2 in agriculture, 1.6 in liberal professions, 8.9 unemployed, 7.3 of no profession; the rest were classified in a miscellaneous category. The proportion of Jews in economic administration was 40.6 percent, and in medical-sanitary administration, 31.9 percent.

The use, and even the knowledge, of Yiddish began to decline sharply in the 20th century, particularly in larger cities: in 1926 only 76 percent of Jews in the Ukrainian SSR claimed Yiddish as their mother tongue (70 percent of the urban and 95 percent of the rural population), while 23 percent listed Russian and barely 1 percent listed Ukrainian. The extent of Russification is evidenced by the fact that only 16 percent had no written knowledge of Russian and as many as 31 percent had no written knowledge of Yiddish (78 percent could not write in Ukrainian).

On the eve of the Second World War there were about 3 million Jews in Ukrainian lands; they constituted 20 percent of the total world Jewish population and 60 percent of the Jewish population of the USSR. During the war the Germans murdered most of the Jews in the territories they occupied (see Holocaust). The only ones who survived were those who had been saved by Ukrainians at the risk of their own lives or were evacuated to the eastern reaches of the USSR before the German advance, and some in Transcarpathia, Bessarabia, and Bukovyna, where there was no direct German occupation, and where the deportation and extermination of the Jewish population was not as complete.

Since the Second World War the Jewish population in the Ukrainian SSR has declined steadily. In the 20 years from 1959 to 1979 it decreased by 24.5 percent, from 840,000 in 1959 to 777,000 in 1970 (which constituted 1.65 percent of the population of Ukraine, and 36.1 percent of the total Soviet Jewish population) and 634,000 in 1979. This decline has been caused by low birth rates, the rise in intermarriages, and, since 1971, mass emigration. Table 4 shows the 1959 and 1970 figures of the distribution of Jews in Kyiv and in oblasts in which they numbered more than 20,000. Jews now live almost exclusively in provincial centers and in larger cities. They are virtually absent in towns and villages.

Cultural life. From the very beginning of mass Jewish settlement in Ukraine, Jewish cultural and religious life was highly developed. The impressive stone synagogues throughout Ukraine serve as interesting historical monuments to Jewish material culture. The more notable ones, such as those in Volhynia (in Dubno, Lutsk, and Liuboml), date back to the 16th–18th centuries. The Cossack uprisings of the 17th century, the destruction wrought by the Cossack-Polish War of 1648–57, and the general social and economic dislocations of the era initiated a period of great change for the Jewish population of Ukraine. Many Jewish scholars fled to the West, where they founded Talmudic centers in Holland, Germany, and Bohemia. Religious disillusionment spread and many Jews sought solace in a variety of ascetic or mystical movements. Hasidism, which was founded in Ukraine by Israel Ba'al Shem Tov, became the dominant religious trend in Western Ukraine. In the late 18th century the Haskalah or Enlightenment movement, inspired by Moses Mendelssohn, emerged. Adherents of this movement sought a synthesis of Jewish religious tradition with the demands of modern life. The Enlightenment movement later fostered the spread of Zionism, which had many adherents in Ukraine.

The rebirth of Hebrew and its application to modern life also originated with Jews from Ukraine. Ahad Ha-Am (1856–1927), who was born in the Kyiv region, is considered the founder of ‘cultural’ or ‘Spiritual’ Zionism. Also of Ukrainian origin are the famous Hebrew lyric poet Hayyim Nahman Bialik (1873–1934) and the poet Saul Tchernichowsky (1875–1943). The brilliant tradition of Yiddish culture in the 16th–18th centuries was continued in Ukraine by Sholom Aleichem (Rabinovich, 1859–1916), who profoundly influenced an entire generation of Jewish writers. After 1920 Chernivtsi became an important center of Jewish culture.

The Jewish press developed rapidly from the mid-19th century. The first serials, published in Russian and Yiddish, appeared in Odesa; they included Rassvet (1860) and Zion (1861). In the early 20th century in Galicia, the Jewish daily Chwila and a number of other periodicals were established in Lviv.

In the Ukrainian SSR during the period 1923–34, Jews benefited from the granting of national rights and freedom for cultural development. Yiddish was recognized as an official language and used in administrative matters in Jewish soviets. Many Jewish periodicals were established; eg, Stern, the official organ of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine and the All-Ukrainian Council of Trade Unions. All laws and government directives were also published in Yiddish. In the Ukrainian SSR in 1925 there were 393 trade and vocational schools in which the language of instruction was Yiddish, attended by 61,400 students or one-third of the total Jewish student population. There were four Jewish pedagogical institutes and separate departments in the Institute of People's Education in Odesa. In 1928, 69,000 students attended 475 Jewish schools, and by 1931 there were 831 schools and 94,000 students. The closing of Jewish schools began in 1933–4, at the same time as the abolition of Ukrainization. By the start of the Second World War, the Jewish educational system had, for all practical purposes, been abolished.

The higher academic institutions devoted to the study of Jewish culture included the Hebraic Historical-Archeographic Commission and Chair of Jewish Culture of the All-Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, which became the Institute of Jewish Culture of the All-Ukrainian Academy of Sciences in 1929. The All-Ukrainian Mendele Mokher Seforim Museum of Jewish culture was established in Odesa, while the Central Jewish Library was located in Kyiv.

Jewish theaters, which had been prominent in the theatrical and artistic life of prerevolutionary Ukraine, continued to exist under Soviet rule. In 1922 permanent Jewish theaters were organized in Kyiv and Odesa, and a Jewish department of the Kyiv Institute of Theater Arts was established in 1934. Many Jewish poets and writers became active in the 1920s, publishing in Yiddish, including Leib Kvitko, David Hofstein, Perets Markish, David Bergelson, Der Nister, Isaac Fefer, D. Feldman, Kh. Hildin, and A. Reizin. Their works were translated into Ukrainian by Pavlo Tychyna, Maksym Rylsky, and others. Jewish cultural activists were subjected to the same wave of repressions in the 1930s as were directed at Ukrainians and many Jewish institutions were closed by the authorities. After the Second World War all expressions of Jewish culture were stifled in Ukraine. From 1950 to 1952 a number of Jewish writers and cultural activists were murdered by the NKVD, among them Bergelson, Markish, Hofstein, Kvitko, Fefer, Pinkhus Kahanovych (Der Nister), and A. Kushnirov.

Ukrainian themes are found in the works of Jewish writers active in Ukraine, such as M. Mokher Seforim (1836–1917), Sholom Aleichem, Sh. Frug, Sh. Asch, and B. Horowitz, and among those active in the diaspora, such as H.N. Bialik, Sh. Bikel, and R. Korn.

A number of Jewish writers became part of the general Ukrainian literary process: the poets Leonid Pervomaisky, Sava Holovanivsky, Ivan Kulyk, Abram Katsnelson; the prose writers Natan Rybak, Leonid Smiliansky; the dramatist L. Yukhvid; the literary historians and critics Yarema Aizenshtok, Aleksandr Leites, Samiilo Shchupak, Illia Stebun (Katsnelson), Oleksander Borshchahivsky, Yevhen Adelheim, and A. Hozenpud. Also active in Ukrainian circles were the historians Yosyf Hermaize and S. Borovoi and the linguist Olena Kurylo. Many of the above were repressed during the purges in the 1930s. In the 1970s and 1980s, the poets Leonid Kyselov (Kiselev) and Moisei Fishbein (the latter emigrated to the West in 1979) also wrote in Ukrainian.

Two of the more prominent translators of Ukrainian poetry were David Hofstein, who published translations of Taras Shevchenko’s poetry in 1937, and A. Klein, who published a collection of translations of Ukrainian folk works in Kolomyia, in 1936. An important role in the popularization of Ukrainian literature was played by Yakiv Orenshtain, the founder and owner of Ukrainska Nakladnia, a publishing house based in Kolomyia and Berlin. It was established in 1903 and in the next 30 years published hundreds of Ukrainian titles.

An interesting development was the attempt made by Jewish émigrés to establish a Ukrainian theater in the United States. In Philadelphia, I. Ginzberg led a Jewish-Ukrainian acting company in 1910–12, I. Elgard (Izydor Elgardiv) led a touring theater group in 1916–17, and D. Medovy led his own Jewish-Ukrainian theatrical company in 1917–28. All of them staged Ukrainian plays and helped popularize them.

The unique nature of Jewish-Ukrainian relations is reflected in the Ukrainian oral tradition. The popular folk song of the traditional spring cycle Ïde ïde Zel’man hearkens back to the days when Jews held leases on Ukrainian churches. Motifs on Jewish privileges appeared frequently in the dumas. One of the so-called younger dumas is called Zhydivski utysky (Jewish Oppressions). In various vertep dramas and intermedes the sympathetic and comic figure of the Jew appears with the Zaporozhian cossack, the noble, and the Gypsy. Among the many Ukrainian authors who have portrayed Jews have been Taras Shevchenko, Ivan Franko, Stepan Rudansky, Yakiv Shchoholiv, Tymotei Borduliak, Modest Levytsky, Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky, Volodymyr Vynnychenko, Oleksander Oles, Arkadii Liubchenko, Leonid Pervomaisky, Mykola Khvylovy, Borys Antonenko-Davydovych, Yaroslav Hrymailo, and Yurii Smolych.

Today the role of Jews in Ukraine has significantly decreased, although they remain the second largest minority after the Russians. (See also Anti-Semitism.)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dubnow, S. History of the Jews in Russia and Poland from the Earliest Times until the Present Day, 3 vols (Philadelphia 1916–20)

Mytsiuk, O. Agraryzatsiia zhydivstva Ukraïny na tli zahal'noï ekonomiky (Prague 1933)

Levitats, I. The Jewish Community in Russia, 1772–1844 (New York 1943)

Greenberg, L. The Jews in Russia: The Struggle for Emancipation, 2 vols (New Haven 1944, 1951)

Baron, S. A Social and Religious History of the Jews, 2nd rev edn, 17 vols (New York 1952–78)

———. The Russian Jew under Tsars and Soviets (New York 1964)

Ukrainians and Jews: A Symposium (New York 1966)

Goldelman, S. Jewish National Autonomy in Ukraine 1917–1920 (Chicago 1968)

Kochan, L. (ed). The Jews in Soviet Russia since 1917 (New York 1970)

Gitelman, Z. Jewish Nationality and Soviet Politics: The Jewish Section of the CPSU (Princeton 1972)

Weinryb, B.D. ‘The Hebrew Chronicles on Bohdan Khmel’nyts’kyi and the Cossack-Polish War,’ HUS, 1, no. 2 (June 1977)

Frankel, J. Prophecy and Politics: Socialism, Nationalism, and the Russian Jews, 1862–1917 (New York 1981)

Levitats, I. The Jewish Community in Russia, 1844–1917 (Jerusalem 1981)

Redlich, S. ‘Jews,’ in Guide to the Study of the Soviet Nationalities: Non-Russian Peoples of the USSR, ed by S. Horak (Littleton, Colo 1982)

Mendelsohn, E. The Jews of East Central Europe between the World Wars (Bloomington, Ind 1983)

Pinkus. B. The Soviet Government and the Jews, 1918–1967: A Documented Study (Cambridge 1984)

Goldberg, J. Jewish Privileges in the Polish Commonwealth (London 1985)

Kleiner, I. From Nationalism to Universalism: Vladimir (Ze'ev) Jabotinsky and the Ukrainian Question (Edmonton and Toronto 2000)

Aster, H.; Potichnyj, P. (eds). Jewish-Ukrainian Relations in Historical Perspective 3rd ed. (Toronto and Edmonton 2010)

Volodymyr Kubijovyč, Vasyl Markus

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 2 (1988). It will be updated.]