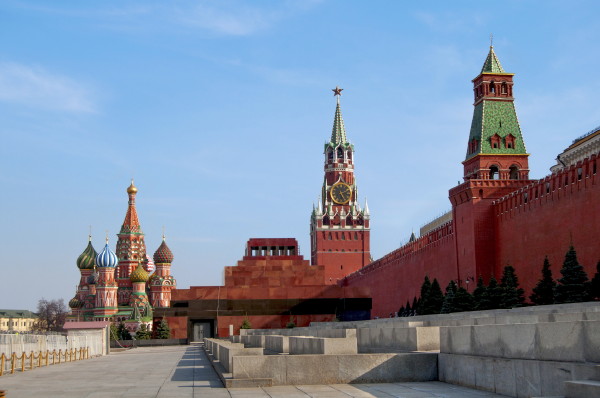

Moscow

Moscow (Russian: Москва; Moskva). The principal city and capital of the Russian Federation and the former USSR. It was founded as the center of a Kyivan Rus’ appanage principality in 1147 by Prince Yurii Dolgorukii of Suzdal, and by the 14th century it was the hub of the Great Muscovite Principality and the seat of the Muscovite Orthodox metropolitan. From 1478 to 1712 Moscow was the center of the unified state of Muscovy. On 12 March 1918 it became the capital of the RSFSR, and on 30 December 1922, the capital of the USSR. Greater Moscow covers an area of 2561.5 sq km and had a population of 12,506,468 in 2018. According to the Soviet censuses, 184,900 Ukrainians lived there in 1970, 252,670 in 1989, and 117,590 in 2018. In 1970 only 37.2 percent gave Ukrainian as their mother tongue. Unofficial sources estimate that 500,000 to 1 million Ukrainians live in Moscow today.

Ukrainian cultural, educational, religious, and political figures began appearing in Moscow almost immediately after the dissolution of Kyivan Rus’ in the late 13th century. Metropolitan Petro of Kyiv and Halych lived and worked in Moscow, and in 1322 he transferred his seat there. In 1389 Metropolitan Cyprian of Kyiv also moved to Moscow and amended church rituals and texts there. In the 14th century Prince Dmytro Bobrok-Volynsky, the son of Koriat-Mykhailo, the Lithuanian prince of Volhynia, married Anna, the sister of Prince Dmitrii Donskoi of Moscow. He distinguished himself as a military leader at the Battle of Kulikovo Pole in 1380 but was killed in 1399 in a clash on the Vorskla River between Vytautas the Great of Lithuania and the Tatar khan Edigei. In 1481 Fedir Bilsky, one of the leaders of a rebellion of Ukrainian princes against Lithuania, fled to Moscow and entered the Muscovite tsar’s military service; later he became an influential political figure there. Similarly, Prince Mykhailo Hlynsky fled to Moscow after an unsuccessful uprising (1507–8) in which he led Ukrainian and Belarusian landowners against King Sigismund I the Old. Ivan Fedorovych (Fedorov), the first printer in Ukraine, began his publishing activities in Moscow, and from 1586 O. Radyshevsky, a Volhynian printer and binder, worked the state press in Moscow.

In the early 17th century joint Polish and Ukrainian Cossack forces advanced on Moscow numerous times, and in 1610 they captured it and held it briefly. In 1618 Hetman Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny’s 20,000-man Cossack army helped Władysław IV Vasa defeat the Muscovite army near Moscow. In 1620, however, Sahaidachny sent envoys to Moscow to offer Mikhail Fedorovich his services.

In the Cossack Hetman state Moscow exerted political influence until the completion of the new Russian capital of Saint Petersburg in 1712. In the nonpolitical sphere, however, the reverse was true: the cultural invasion of Moscow by Ukrainians forever altered church life, literature, and education there.

After the Pereiaslav Treaty of 1654 political relations between Ukraine and Muscovy changed. In 1653 the Cossack envoy Kindrat Burliai had been sent to Moscow to engage in preliminary negotiations for the treaty, which was signed there in March 1654. Col Antin Zhdanovych of Kyiv traveled to Moscow on a diplomatic mission in 1654, after the treaty was signed, and Petro Zabila journeyed there several times in 1654–5 as Acting Hetman Ivan Zolotarenko’s envoy, and in 1665 with Hetman Ivan Briukhovetsky, the first head of the Cossack state to travel to Moscow to petition the tsar. Fedir Korobka, the general quartermaster, was sent to Moscow as envoy of Hetmans Bohdan Khmelnytsky, Ivan Vyhovsky, and Yurii Khmelnytsky. Later the tsars frequently summoned hetmans (eg, Ivan Mazepa) to Moscow.

As Ukraine’s autonomy was eroded, Moscow became a place of exile and even imprisonment of its political leaders. Ivan Krekhovetsky, the general judge under Hetman Pavlo Teteria, was captured in 1665 by Muscovite forces and exiled to Moscow. Hetman Petro Doroshenko was ordered deported from Ukraine by the tsar and was forced to live in Moscow in 1677–9. After the defeat of Hetman Ivan Mazepa at the Battle of Poltava many Cossack officers fell into disfavor and were forced to live in Moscow (eg, Hryhorii Hertsyk, Ivan Charnysh, Ivan P. Maksymovych, and Vasyl Zhurakovsky). Others (eg, Dmytro Horlenko) moved there of their own accord.

The Kyivan Mohyla College (later Kyivan Mohyla Academy) played a significant role in the development of Muscovite education and church life. In 1649 the college sent Yepifanii Slavynetsky and Arsenii Koretsky-Satanovsky, and later, D. Ptytsky, to Moscow. Slavynetsky worked there as a translator, pedagogue, and lexicographer for 26 years. He founded the first Greco-Latin school in Moscow in 1653 and served as its principal. After the Pereiaslav Treaty of 1654 increasing numbers of Ukrainians visited or moved to Moscow. Usually they resided in the ‘Little Russian quarter,’ known as the Maloroseika, the main street of which is now named after Bohdan Khmelnytsky.

In the late 17th century seven monasteries in Moscow were headed by Ukrainians and Belarusians. Ukrainians exerted considerable influence on the city’s cultural development and were instrumental in implementing Patriarch Nikon’s church reform. In 1665 Simeon Polotsky, a graduate of the Kyivan Mohyla College, initiated a Slavonic-Greco-Latin Academy in Moscow modeled on the Kyivan college. Havrylo Dometsky, who was in constant theological conflict with the Russian church authorities, served as an archimandrite in Moscow.

Under Peter I Ukrainian cultural figures continued to be exiled to Moscow or were invited there or moved there to advance their careers. Stefan Yavorsky and Teofan Prokopovych moved there and helped Peter to attract other scholars and church figures to Moscow. In his capacity as exarch Yavorsky instructed Metropolitan Varlaam Yasynsky of Kyiv to have the Kyivan Mohyla Academy send its professors H. Hoshkevych, M. Kansky, R. Krasnopolsky, O. Sokolovsky, A. Streshovsky, and Y. Turoboisky to Moscow. Kyivan scholars often took senior students along in order to provide a good example for Muscovite students. According to S. Smirnov, between 1701 and 1763, 95 professors of the Kyivan academy (18 of 21 rectors and 23 of 25 prefects) transferred to the Moscow Academy. Ukrainians who were prominent at the Moscow academy included Teofilakt Lopatynsky, Inokentii Kulchytsky, Havryil Buzhynsky, G. Vyshnevsky (rector in 1722–8), Varlaam Lashchevsky (rector in 1752–4; author of a Greek grammar used in all theological seminaries in Russia), Ya. Blonytsky (author of a Greek-Slavonic and a Slavonic-Greek-Latin dictionary), Arsenii Mohyliansky, S. Kalynovsky, and Heorhii Shcherbatsky.

From the mid-18th century the number of Ukrainian professors in Moscow decreased because of the rise of native scholars and because Catherine II discouraged Ukrainians from traveling to Moscow. Ukrainian scholars who studied or worked in Moscow include the historians Mykola Bantysh-Kamensky, Yakiv M. Markovych, and M. Zahorovsky (author of a topographic description of Kharkiv vicegerency, 1787); the jurist Semen Desnytsky; the philosopher Semen Hamaliia; the medical practitioners Ivan Andriievsky, H. Mokrenets (lecturer at the Medical Surgical School from 1787 and chief surgeon at the Moscow hospital in 1790–1800), P. Pohoretsky (a graduate of the Kyivan Mohyla Academy who taught at the Moscow Medical Surgical School and developed Russian medical terminology), Illia Rutsky, and Yosyp Tykhonovych; the architects Andrei Melensky, M. Mostsepanov, and Ivan Zarudny; the engraver Mykhailo Karnovsky; the sculptor Ivan P. Martos; the painter Apollon Mokrytsky; and the conductors and composers Y. Zahvoisky, Mykola Dyletsky, Artem Vedel, and Havrylo Rachynsky.

Ukrainian cultural influence troubled Muscovite conservative circles, particularly the clergy, who suppressed Ukrainian publications imported by Ukrainian chumaks and sought to eliminate Ukrainian influences in church, music, rites, and homiletics. Extreme prejudice gave rise to the practice of forcing Ukrainian priests and monks in Muscovy to be rebaptized. Ukrainians were readily invited to work in Moscow, but any manifestation of Ukrainian influence was staunchly opposed. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries attitudes changed, and Ukrainian folk songs, legends, and themes introduced by Ukrainian writers and artists (eg, Vasilii Narezhny and Nikolai Gogol) became popular among the Muscovite intelligentsia.

In the 19th century, after the decline of the Kyivan Mohyla Academy, many Ukrainians studied at Moscow University and other Muscovite schools. Many later remained there as scholars, bureaucrats, economists, cultural figures, and administrators. In the early 19th century Ukrainians in the city created their own organizations, and Moscow became an important Ukrainian political center. From the 1820s Ukrainian works (eg, Hryhorii Kvitka-Osnovianenko’s Malorossiiskie povesti [Little Russian Novelettes]) were published there. Notable Ukrainians who worked in Moscow included the historians Osyp Bodiansky, Mykhailo Maksymovych, Mykola Markevych, Venedykt Ploshchansky, Yurii Venelin, and Dmytro Yavornytsky; the philologists Vasyl P. Maslov, Ahatanhel Krymsky, and Mykola I. Storozhenko; the pedagogue Illia Derkachov; the journalist and archeologist Oleksa Hattsuk; the economist Ivan Myklashevsky; the scientists Antin Prokopovych-Antonsky and Volodymyr Vernadsky; the folklorist Mykola Yanchuk; the philosopher Pamfil Yurkevych; and the art historian Oleksii Novytsky.

Many Ukrainian actors and singers worked in Moscow’s theaters and opera houses, and over 200 worked and performed with the Moscow philharmonic orchestra and at the conservatory. The more outstanding performers included I. Butenko (operatic bass, 1852–7), Mikhail Shchepkin, Semen Hulak-Artemovsky, Mykhailo Donets, Mariia Deisha-Sionytska, Platon Tsesevych, Ivan Alchevsky, O. Stepanova (a soloist at the Bolshoi Theater in 1912–44), and the composer Pavlo Senytsia.

Ukrainian organizational activity in Moscow was initiated by students at Moscow University. They were supported by the Ukrainian professors there. The number of Ukrainian students in the city grew steadily, and by 1908 the 250-member Ukrainian Student Hromada in Moscow was the largest student organization in the city. In the years 1810–60 an average of 15 to 20 Ukrainian students annually studied in Moscow; most had private stipends. In the 1860s the annual number of students rose, to reach 63 in 1865. In the late 1850s the first zemliatstva, associations uniting students from the same region, were organized with the aim of providing mutual assistance and promoting cultural activity. From 1859 to 1866 the Ukrainian Student Hromada operated clandestinely and had its own underground library. Its leaders included Illia Derkachov, P. Kapnist (grandson of Vasyl Kapnist), M. Lazarevsky, I. Rohovych (a privatdocent at Moscow University from 1872), V. Rodzianko, M. Shuhurov, I. Sylych, and Feliks Volkhovsky. The organization was uncovered and liquidated because of its ‘separatist’ tendencies, and its 52 members were blackballed as ‘unreliable.’ The hromada was re-established only in 1898 (by Volodymyr Doroshenko, among others), and it continued to meet secretly until 1905, when it became a legal organization. In 1912 it was headed by Mykola M. Kovalevsky. Each year Ukrainian students gathered to commemorate Taras Shevchenko.

In the early 20th century, particularly after the Revolution of 1905, Ukrainian life in Moscow became more dynamic and political. During the period of the so-called Stolypin reaction many members of the Ukrainian intelligentsia avoided persecution in Ukraine by fleeing to Moscow. In the early 1910s there were 18,000 Ukrainians in the city. In 1909 Ivan Alchevsky, Mykhailo Donets, S. Khvostov, H. Kozlovsky, Antonina Nezhdanova, and others organized the Ukrainian Music and Drama Hromada, which was later registered as the Kobzar circle. It was headed by Khvostov and Alchevsky. During the First World War it was banned by the tsarist regime.

Ukrainian scholars in Moscow belonged to the Society of Slavic Culture, led by Fedor Korsh, and constituted a Ukrainian section therein. Among its members were Bohdan Kistiakovsky, V. Khvostov, Symon Petliura, Volodymyr Picheta, Oleksander Salikovsky, and Mykola Yanchuk.

The public commemoration of the 50th anniversary of Taras Shevchenko’s death in 1911, organized by a committee headed by S. Khvostov, was a major event for the Ukrainian community in Moscow. It was significant because such commemorations were prohibited in Kyiv and elsewhere in Russian-ruled Ukraine. Events included an exhibition of Shevchenko’s art organized by Oleksii Novytsky at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture; an official gathering at Moscow University, at which Fedor Korsh, Ahatanhel Krymsky, Novytsky, and Volodymyr Picheta spoke; a celebration at the literary and art club, with speeches by Korsh and Liubov Yanovska; and performances of excerpts from Shevchenko’s play Nazar Stodolia and Mykola Arkas’s opera Kateryna. Materials from and about the celebrations were published as a collection in Moscow in 1912. Preparations for the celebration of Shevchenko’s centenary in 1914 were begun but were called off after such commemorations were banned in Ukraine.

During the revolutionary upheaval in Moscow in 1906, the first Ukrainian illustrated weekly in the Russian Empire, Zoria (Moscow), was established. Ukrainian journalists living in Moscow also contributed to the Russian press: K. Danylenko (Russkoe slovo), A. Bondarenko and H. Kozlovsky (Stolichnaia molva), Oleksander Salikovsky (Russkiia vedomosti), V. Hiliarovsky, M. Levytsky, and V. Panchenko. In 1912–17 the monthly journal Ukrainskaia zhizn’ was published in Moscow in Russian to inform society in the Russian Empire about the Ukrainian question. Edited by Symon Petliura and Salikovsky, it was the unofficial organ of the Moscow branch (est 1907) of the clandestine Society of Ukrainian Progressives. Two volumes of Ukraïns’kyi naukovyi zbirnyk, three collections of Mykola Filiansky’s poetry, and a collection of plays were also published in Moscow in that period. During the First World War L. Solohub and Volodymyr Vynnychenko edited the weekly Promin’ (Moscow) (1916–7), and Ukrainian political life in Moscow revolved around Ukrainskaia zhizn’ and Promin’.

During the February Revolution of 1917 Ukrainians in Moscow issued a joint declaration of the Union of Ukrainian Federalists, the Moscow Committee of Ukrainian Socialists, the editorial boards of Ukrainskaia zhizn’ and Promin’ (Moscow), and the Ukrainian section of the Society of Slavic Culture. The declaration demanded the introduction of Ukrainian government institutions, courts, and schools in Ukraine and of the territorial organization of the armed forces. In late May 1917 a Ukrainian Council was founded in Moscow, consisting of Oleksander Salikovsky (chairman), A. Khrutsky, A. Pavliuk, and Antin Prykhodko. In the April 1917 elections to the Central Rada Mykola Shrah and P. Sikora were elected as delegates from Moscow.

In March 1918 Moscow became the capital of Soviet Russia. That year the first two CP(B)U congresses were held there, and the Hetman government sent a delegation to Moscow in an attempt to normalize relations with the Soviet state and appointed A. Kryvtsov its consul general there. In early 1919 the Directory of the Ukrainian National Republic sent a diplomatic mission headed by Semen Mazurenko to Moscow to negotiate, unsuccessfully, with the Soviet government.

Under Soviet rule Moscow once again became the center of an empire, where all political, economic, and cultural power was concentrated. Thereafter all essential decisions concerning Soviet Ukraine were made in Moscow, and the various official representations of the Ukrainian SSR in Moscow served the interests of Russian imperialism. Until the end of 1922 the Ukrainian SSR had a diplomatic mission in Moscow. Thereafter a Soviet Ukrainian permanent representation was based there.

In the 1920s the Ukrainian community in Moscow continued its cultural activity. The Ukrainian Shevchenko Club organized literary readings, debates, and Taras Shevchenko jubilees in which thousands participated.

In 1924 an association of Ukrainian writers, Selo i Misto (SiM), with branches throughout the RSFSR, was established in Moscow. Headed by Volodymyr Gadzinsky, Kost Burevii, and Hryhorii (Heo) Koliada, SiM also ran a publishing house that issued works by Gadzinsky, Koliada, and A. Harasevych, a two-volume edition of Taras Shevchenko’s works, and the journal Neolif. SiM was liquidated in 1927.

Under Soviet rule many Ukrainians continued to study and work in the ‘imperial’ capital. They included literary scholars, such as M. Alekseev (a member of the USSR Academy of Sciences who headed the council on Ukrainian literature of the USSR Writers' Union), S. Bohuslavsky (a professor at Moscow University), Mykola Gudzii, Mykhailo Parkhomenko, M. Zozulia, and O. Deich, who lived in Moscow from 1925 to 1972, published works there on Ivan Franko, Mykola Kulish, Lesia Ukrainka, and Taras Shevchenko, and helped persecuted Ukrainian literary figures, such as Maksym Rylsky, Ivan Drach, and Les Taniuk. Other scholars included the neuropathologist Ye. Benderovych, the soil scientist Kostiantyn Gedroits, the translator I. Karabutenko (secretary of the council on Ukrainian literature of the Writers' Union from 1950 to 1985), the metallurgist H. Kashchenko, the chemist Volodymyr Kistiakovsky, the musicologist and ethnographer Klyment Kvitka, the economist Petro Liashchenko, and the geologist Volodymyr Luchytsky.

In 1924–34 the Moscow Ukrainian Theater of the RSFSR was active in Moscow under the direction of H. Behicheva, a former assistant at the Berezil theater in Kharkiv. In 1933 Les Kurbas worked briefly at the Jewish Theater in Moscow before his arrest. Many graduates of Ukrainian conservatories and theater schools have worked at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow. They include V. Borysenko, O. Byshevska (from 1934), O. Holoborodko, Andrii Ivanov, S. Korkoshko, Ivan Kozlovsky, I. and L. Maslennykova, Mykhailo Mykysha, Ye. Nesterenko, Bela Rudenko, and N. Shpiller. The famous director Aleksandr Tairov was born in Romny, and studied at Kyiv University. He founded the Chamber Theater in Moscow and staged plays there by Ukrainian playwrights, such as Oleksander Korniichuk, Mykola Kulish, Leonid Pervomaisky, and Yurii Yanovsky, including the premiere of Kulish’s Patetychna Sonata (Sonata Pathétique) in 1931.

During the Stalinist period many Ukrainian community, cultural, scholarly, and artistic figures fled from repression in Ukraine or were exiled to Moscow. A few survived the terror, among them S. Buniak, A. Chuzhy (a futurist poet), and Yu. Illina, all of whom continue to write and are published in Ukrainian in Moscow, and I. Stadniuk, the author of Liudi ne angely (People Are Not Angels, 1962), a Russian-language novel about the famine in Ukraine.

During the Second World War the writers Oleksander Dovzhenko, Oleksander Korniichuk, Andrii Malyshko, Maksym Rylsky, Yurii Smolych, Volodymyr Sosiura, and Pavlo Tychyna lived in Moscow, and Ukrvydav, a publisher of materials in Ukrainian destined for the front, functioned there. In 1940 the Ukrainskaia Kniga bookstore was opened in Moscow’s Arbat district; many readings by Ukrainian writers were held there.

From 1936 official 10-day festivals of Ukrainian art and literature were held in Moscow. Reduced to single-day events in the 1970s, they served as vehicles of propaganda promoting the fiction of the ‘flowering’ of Ukrainian literature and praising Russian-Ukrainian friendship. Standardized commemorations of Ukrainian writers, such as Ivan Franko, Lesia Ukrainka, Taras Shevchenko, and Hryhorii Skovoroda, were also held.

The postwar Ukrainian theater directors Les Taniuk and R. Viktiuk worked in Moscow. Forced to work there were the film directors Oleksander Dovzhenko (he is buried in Moscow) and Ihor Savchenko. The Ukrainian-born director Serhii Bondarchuk made his career in Moscow. Postwar Ukrainian writers who studied in Moscow include Lina Kostenko, Pavlo Movchan, Hryhir Tiutiunnyk, Ivan Drach, Mykola Vinhranovsky, and L. Cherevatenko.

In the 1960s the Ukrainian community in Moscow became more active. Ukrainian students there began holding independent Taras Shevchenko celebrations and gatherings, at which they sang Ukrainian songs and read proscribed literary works. They were aided in their efforts by the writer and former political prisoner M. Kutynsky (1890–1974), who compiled a 2,000-page biographical dictionary of 7,000 Ukrainian historical and cultural figures (serialized in the journal Dnipro since 1990).

In the last few years of Soviet rule under Mikhail Gorbachev, the Ukrainian community was reactivated. Demonstrations supporting the lifting of the ban on the Ukrainian Catholic church and Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox church were held there. In 1988 the Ukrainian community leaders E. Deich, S. Hnidina, O. Ivanchenko, V. Liubun, I. Movchan, I. Shyshov, and A. Siry established the Slavutych Society of Friends of Ukrainian Culture, headed by the former cosmonaut Pavlo Popovych and Les Taniuk, and organized a Ukrainian library. A Ukrainian Youth Club was also established within the local Komsomol, led by V. Martyniuk and P. Zhovnerenko. In 1989 the Ukrainian Helsinki Association (later Ukrainian Republican party) established an active branch in Moscow, represented by A. Dotsenko, O. Horbatiuk, and M. Muratov; the Society for the Support of the Popular Movement of Ukraine (Rukh) was also founded, headed by Ye. Siary; and an independent journal, Ukrainskii vopros, edited by S. Matsko, began appearing. Throughout the Gorbachev period the Ukrainian poet Vitalii Korotych was editor of the popular Moscow magazine Ogonëk and in that capacity was instrumental in promoting glasnost and perestroika throughout the USSR.

Ukrainian landmarks in Moscow include a monument to Taras Shevchenko erected in 1964 (sculptors, Anatolii Fuzhenko, M. Hrytsiuk, and Yulii Synkevych), the Shevchenko Library, the Lesia Ukrainka Library, and the building of the Permanent Representation of Ukraine.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kharlampovich, K. Malorossiiskoe vliianie na velikorusskuiu tserkovnuiu zhizn' (Kazan 1914; The Hague and Paris 1968)

Kozlovs'kyi, H. ‘Z zhyttia ukraïns'koï kol’oniï v Moskvi v 1900 r. (“Ukraïns'ka Muzychno-Dramatychna Hromada”),’ Z mynuloho, 1 (Warsaw 1938)

Doroshenko, V. ‘Ukraïns'ka students'ka hromada u Moskvi,’ Z mynuloho, vol 2, Ukraïns'kyi students'kyi rukh u rosiis’kii shkoli (Warsaw 1939)

Doroshkevych, O. Ukraïns'ka kul'tura v dvokh stolytsiakh Rosiï (Kyiv 1945)

Kovalevs'kyi, M. Pry dzherelakh borot'by: Spomyny, vrazhennia, refleksiï (Innsbruck 1960)

Stovba, O. ‘Ukraïns'ka students'ka hromada v Moskvi 1860-kh rokiv,’ in Zbirnyk na poshanu prof. d-ra Oleksandra Ohloblyna, ed V. Omel'chenko (New York 1977)

Ivan Shyshov, Arkadii Zhukovsky

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 3 (1993).]

.jpg)