Painting

Painting [малярство; maliarstvo]. The portrayal or rendering of pictures on a flat surface with a variety of pigments in such media as tempera, oils, watercolors, and acrylics. In Ukraine the oldest surviving paintings are frescoes and murals found at archeological sites of ancient states on the northern Black Sea coast, where they were preserved on the walls of tombs. One of the earliest portraits is a head of a young man (4th century AD) on a stone slab in the encaustic technique found at the ruins of Chersonese Taurica. Some early (3rd century) Christian frescoes have been preserved in the Crimea.

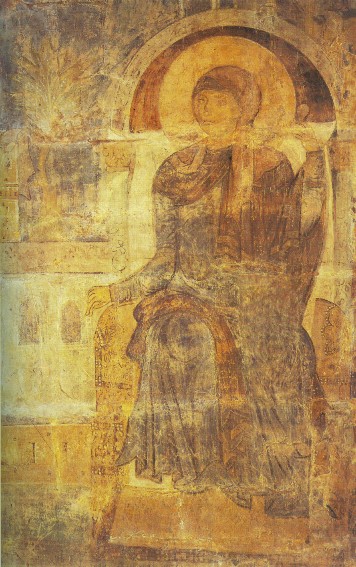

Fragments of frescoes from the medieval Kyivan Rus’ period have been found in the Church of the Tithes in Kyiv (late 10th century), the Cathedral of the Transfiguration in Chernihiv (11th century), and the Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv (early 11th century). Some of the frescoes of Saint Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery in Kyiv, which was demolished by the Soviet authorities in 1934–5, are preserved at the Saint Sophia Museum in Kyiv. In style these 11th-century frescoes are similar to those of the middle period of Byzantine art. The frescoes in the Church of Saint Cyril's Monastery in Kyiv (mid-12th century) are more realistic and display Balkan influences.

According to the Primary Chronicle portable icons were already being painted in the 10th and 11th centuries, but none so old have survived to our time. Perhaps the oldest extant icon from Kyiv is an icon of the Mother of God with Saint Anthony of the Caves and Saint Theodosii of the Caves that belonged to the Svensk Monastery near Briansk, the so-called Mother of God of the Caves or The Svensk Mother of God. Among other oldest icons from Kyiv are Vyshhorod (Vladimir) Mother of God (12th century), which was of Greek origin, is now in the Tretiakov Gallery in Moscow, as are two other icons once in Kyiv, the Mother of God Great Panagia and Saint Demetrius of Thessalonica. Examples of medieval Ukrainian painting can also be found in illuminated manuscripts.

With the decline of Kyivan Rus’ the center of political power and culture shifted to the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia, and only a few paintings (mostly in Western Ukraine) survived the turbulent years of the 13th-century Mongol invasion—the frescoes in the rotunda chapel in Horiany, in Transcarpathia, and in the Armenian Cathedral in Lviv, built in 1363. Two of the better-known surviving icons are Saint George from Stanylia and The Mother of God from Lutsk (late 13th to early 14th century), both rendered in the Byzantine-Ukrainian tradition of icon painting. Ukrainian iconographers were commissioned by Kings Casimir III the Great and Władysław II Jagiełło to decorate churches in the Wawel royal castle in Cracow, in the Holy Trinity Chapel in Lublin, and in the Sandomierz Cathedral.

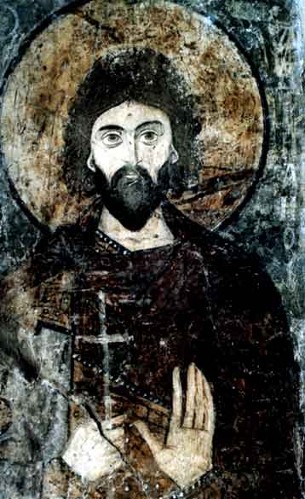

In the 15th and 16th centuries there emerged a Galician school of icon painting, in which adherence to Byzantine iconography was tempered by personal interpretations, individual variations, and Western influences. In The Mother of God Hodegetria from Krasiv (second half of the 15th century), for example, Mary's face is considerably rounder and more in keeping with those of local models, and Jesus wears an embroidered shirt. Influences of the Gothic style may be seen in the architecture of some icons, such as Saints George and Parasceve from Korchyn (late 15th century). During the Renaissance icons gradually lost their rigidity and became more realistic. The development was first apparent in the modeling of facial features, as in Christ Pantocrator (late 15th century) from Starychi, in the Lviv region, and in the use of local landscapes, as in Transfiguration (1575) from Yabluniv. It was not until the 17th century, however, that Byzantine traditions began giving way to the baroque, which introduced secular themes, three-dimensional forms, and movement in icons (eg, the iconostases in Velyki Hrybovychi [1638], near Zhovkva in Galicia, and in Velyki Sorochyntsi, near Myrhorod [early 18th century]). Two of the better-known icon painters at the time were Ivan Rutkovych and Yov Kondzelevych, whose work was influenced by Western religious painting and iconography. The influence is evident in the theme, composition, and realistic rendering of Christ by the Well (1696–99) in the iconostasis painted by Rutkovych in the Church of the Nativity in Skvariava Nova, near Zhovkva.

In Ukraine portrait painting as a separate genre emerged during the Renaissance (16th century) and was strongly influenced by the icon tradition. The first portraits were those of benefactors (Jan Herburt, ca 1578), which were hung in churches, and memorial likenesses painted on wood or metal panels for coffins (Varvara Larbysh, 1635). Portraits not used for religious purposes did not emerge until the 17th century. They included official portrayals of nobles and Cossack hetmans and Cossack starshyna officers, known as ‘parsunni’ (personal) portraits, as well as more intimate portraits of nobles and burghers.

The secular themes, illusionistic space, local colors, and realistic representations that the baroque brought from Western Europe remained strong in Ukrainian art until the imposition of socialist realism in the 1930s. Painting expanded thematically to include a variety of portraits, battle scenes, genre scenes, and presentations of historical compositions.

As Ukrainian Cossack autonomy was eroded by the tsars in the 18th century, opportunities for Ukrainian painters to have their talents recognized locally became increasingly limited. Consequently, many were attracted to the newly established Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg (est 1757), which cultivated the classicist style of painting then popular in Europe. Better-known Ukrainian artists who pursued their careers at the academy and contributed significantly to the development of art in Russia were Antin Losenko, K. Holovachevsky, Ivan Sabluchok, Dmytro H. Levytsky (one of the greatest portraitists in the Russian Empire), and Volodymyr Borovykovsky.

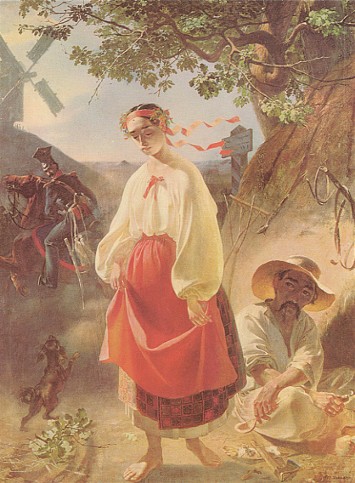

The emigration of Ukrainian artists to Saint Petersburg deprived Ukrainian painting of its most creative talents. The exception was Taras Shevchenko, who devoted most of his painting (like his writing) to Ukrainian interests and has been considered the father of modern Ukrainian painting. Shevchenko painted numerous portraits, self-portraits, and landscapes which recorded the architectural monuments of Ukraine. While in exile he depicted Kirgiz (see Kirgizia) folkways and the surrounding countryside, as well as the degradation of tsarist prisons and the first pictorial indictments of the horrors of Russian army life and punishment. Shevchenko was also concerned with formal problems of the effects of light and dark.

During the 19th century landscape painting appeared as a separate genre, and not only in the work of Taras Shevchenko. Inspired by romanticism, Ivan Soshenko recorded the pastoral settings of rural scenery, and Arkhyp Kuindzhi, Ivan Aivazovsky, Serhii Vasylkivsky, Ivan Pokhytonov, and Serhii Svitoslavsky devoted their efforts to depicting rural scenery at its most beautiful.

A Romantic idealism was reflected in the portraits of Apollon Mokrytsky, particularly in that of his wife (1853), as well as in Havrylo Vasko's Youth from the Tomara Family (1847) and Pavel Shleifer's portrait of his wife (1853).

In the last few decades of the 19th century Ukrainian painters studying art in Russia were influenced by the Peredvizhniki society, formed in 1870 in Saint Petersburg by artists who were opposed to the classicist traditions of the Academy of Arts (see Academism). Artists of Ukrainian origin who became active in the society were Ilia Repin, Nikolai Ge, Ivan Kramskoi, Arkhyp Kuindzhi, Mykola Kuznetsov, Kyriak Kostandi, Petro Levchenko, Porfyrii Martynovych, Oleksander Murashko, Petro Nilus, Leonid Pozen, Mykola Pymonenko, and Serhii Svitoslavsky. Not all of them remained committed to it. Many other artists were influenced by its ideas to paint realistic genre scenes, including Fotii Krasytsky, Solomon Kyshynivsky, and Serhii Vasylkivsky. Mykola Samokysh was primarily known for his Cossack and battle scenes, and Ivan Izhakevych depicted peasant life.

In Austrian-ruled Western Ukraine artists adapted to European trends, particularly those prevalent in Vienna and Cracow, where some of them had studied. Among them were Luka Dolynsky, Kornylo Ustyianovych, and Teofil Kopystynsky, all of whom depicted rural life through a romanticized ethnographic prism and were active in decorating churches. Both Mykola Ivasiuk, who was known for his panoramic historical canvases, and Antin Manastyrsky remained dedicated realists (see Realism).

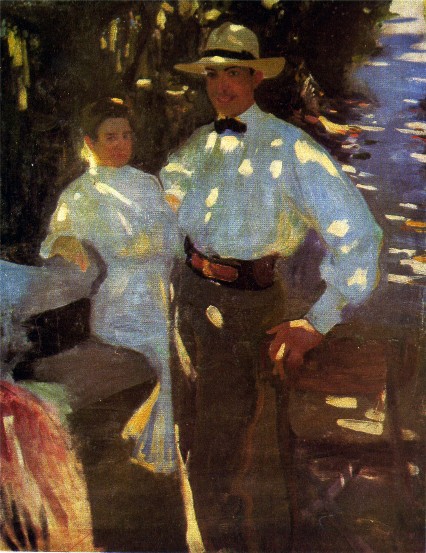

Impressionism made itself felt in the work of several Kyiv artists who had worked in Paris, including Petro Levchenko, Abram Manevich, Mykola Burachek, Oleksander Murashko, and the exceptionally versatile Vasyl H. Krychevsky. The new style stimulated an interest in intimate glimpses of ordinary events and urban scenery (eg, Levchenko's Reading a Letter and Murashko's Flower Vendors). Above all else it altered the palette of most artists for many years to come. In Western Ukraine impressionism influenced the work of Ivan Trush (although for the most part he remained a realist), Osyp Kurylas, and Olena Kulchytska. Artists who worked in the impressionist style included Modest Sosenko and Yaroslav Pstrak.

Whereas the artists in Western Ukraine for the most part remained under the influence of Western European art movements, those working in Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Odesa developed close ties with Moscow and Saint Petersburg (later Leningrad). Thus Pavel Volokidin was influenced by the World of Art movement, and Petro Kholodny and M. Sapozhnikov created symbolist paintings. The early 20th-century avant-garde movement had a direct impact on Ukrainian painting. Artists born in Ukraine, as well as those who considered themselves Ukrainian by nationality, were in its vanguard. The most prominent of them were Kazimir Malevich, David Burliuk, Vladimir Burliuk, Alexandra Ekster, V. Baranoff-Rossiné, Oleksander Bohomazov, and Vladimir Tatlin. A. Ekster introduced futurism to Kyiv and helped bring avant-garde exhibitions to Ukraine.

During the brief period of Ukrainian independence the Ukrainian State Academy of Arts (1917–22) was established in Kyiv. It and its successor, the Kyiv State Art Institute, made it possible for Ukrainian painters to pursue advanced art training in their homeland. Vasyl H. Krychevsky was its first rector, and one of the most influential teachers was Mykhailo Boichuk, who revived fresco painting and aspired to develop an art for the masses based on a combination of Ukrainian traditions and Western models instead of the Peredvizhniki. Subsequently Boichuk and his followers (the ‘Boichukists’)—his brother, Tymofii Boichuk, his wife, Sofiia Nalepinska, Oksana Pavlenko, Vasyl Sedliar, Ivan Padalka, Ivan Lypkivsky, P. Ivanchenko, A. Ivanova, S. Kolos, Kyrylo Hvozdyk, Manuil Shekhtman, and Mykola Rokytsky—were, in most cases, victims of the Stalinist terror of the 1930s.

Fedir Krychevsky, who also taught at the Ukrainian State Academy of Arts and the Kyiv State Art Institute, was influenced by impressionist colors, but remained a realist in his modeling of form and space (eg, Self-Portrait in a Sheepskin Coat, 1926). Others who adhered to realism included Mykhailo Kozyk, Hryhorii Svitlytsky, Solomon Kyshynivsky, Semen Prokhorov, Mikhail Sharonov, and Illia Shulha.

During the relatively liberal period of the 1920s in Soviet Ukraine, a variety of styles flourished. Cubo-futurist and constructivist paintings were produced by Vasyl Yermilov in Kharkiv and Oleksander Bohomazov, Viktor Palmov, and Anatol Petrytsky in Kyiv. Petrytsky painted over a hundred portraits of Ukrainian personalities, most of which disappeared or were destroyed during the Stalinist terror. Vadym Meller and K. Sikorsky experimented with abstraction; Yukhym Mykhailiv, who was fascinated with mythology, continued the traditions of symbolism.

In interwar Western Ukraine under Polish rule, the most prominent Lviv painter was Oleksa Novakivsky, who began as an impressionist and was attracted by French postimpressionism and expressionism. He painted portraits and landscapes, and through his art school (see Novakivsky Art School) he influenced an entire generation of future artists, including Ivanna Vynnykiv, Sviatoslav Hordynsky, and Myron Levytsky, who went on to explore modern trends in art. Roman Selsky experimented with surrealism; Mykola Butovych, Pavlo Kovzhun, and Robert Lisovsky explored cubism and abstraction. The revival of the Byzantine style (see Neo-Byzantinism) of church mural painting and decoration in Western Ukraine was encouraged by Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky, a great patron of the arts. It was practiced by Osyp Kurylas, Mykhailo Osinchuk, Vasyl Diadyniuk, and Yuliian Butsmaniuk.

Artists working in Transcarpathia under interwar Czechoslovak rule, including Yulii Virah, Yosyp Bokshai, Adalbert Erdeli, and Emilian Hrabovsky, had ties with Central and Western European art movements and used bold, vibrant colors. Later Andrii Kotska, Zoltan Sholtes, Fedir Manailo, E. Kondratovych, and H. Hliuk continued the coloristic traditions.

In the 1930s all avant-garde activities in Soviet Ukraine came to a halt with the introduction of socialist realism as the only literary and artistic method permitted by the communist regime. Painting was limited to naturalistically rendered thematic canvases of the Bolshevik October Revolution of 1917 and its champions, glorification of the Soviet state and its leaders, portraits and genre scenes of happy workers and peasants, and romanticized depictions of war and its heroes. Landscapes and still-life compositions were discouraged and all departures from the socialist-realist canon were condemned as ‘formalist,’ and their creators were discriminated against and sometimes persecuted. Among the more prominent socialist-realist artists were Volodymyr Kostetsky, Karpo Trokhymenko, Mykhailo Bozhii, Serhii Hryhoriev, Dmitrii Shavykin, Oleksii Shovkunenko, Oleksandr Lopukhov, and O. Khmelnytsky.

The narrow confines of socialist realism were widened somewhat after the death of Joseph Stalin, particularly during Nikita Khrushchev's cultural thaw. Artists such as Roman Selsky, Margit Selska, Vitold Manastyrsky, Tetiana Yablonska, and Viktor Zaretsky turned to Ukrainian folklore and folk themes, more vibrant colors, and a flattened rendering. Younger artists, such as Karlo Zvirynsky, V. Basanets, V. Sumar, and Valerii Lamakh, experimented with abstraction; Liubomyr Medvid, Petro Markovych, Ivan Zavadovsky, and Ivan Marchuk, with surrealism; and Volodymyr Patyk and Volodymyr Loboda, with expressionism.

The curtailing of artistic freedom in 1965 and again in 1972, as well as the arrest and sentencing of prominent Ukrainian writers and artists, including Opanas Zalyvakha and Stefaniia Shabatura, gave rise to nonconformism. In the 1970s Ukrainian artists participating in the exhibitions of nonconformist art in Moscow and Leningrad included N. Haiduk, Feodosii Humeniuk, Volodymyr Makarenko, Volodymyr Naumets, Vitalii Sazonov, Volodymyr Strelnikov, and Liudmyla Yastreb. Other artists, such as Karlo Zvirynsky in Lviv and Oleksandr Dubovyk, Ivan Marchuk, and Yevhen Petrenko in Kyiv, stopped exhibiting.

After the failure of the Ukrainian struggle for independence (1917–20), a good number of Ukrainian painters became émigrés. Among those working in Warsaw were Petro P. Kholodny, Petro Mehyk, and Petro Andrusiv. In Prague Ivan Kulets and Halyna Mazepa explored cubism and abstraction, and Kateryna Antonovych was inspired by Mykhailo Boichuk’s monumentalism and impressionism. Of the more prominent painters who settled in France Sofiia Levytska worked in a postimpressionist manner and later took part in cubist exhibitions, and Oleksa Hryshchenko and Vasyl Khmeliuk painted in an expressionist manner. Mykhailo Andriienko-Nechytailo used constructivist elements in his abstractions. Others who worked in Paris in a variety of figurative styles included Severyn Borachok, Mykola Hlushchenko, Sofiia Zarytska, Mykola Krychevsky, Petro Omelchenko, Vasyl Perebyinis, V. Palisadiv, and O. Savchenko-Bilsky. After the Second World War they were joined by Ivanna Vynnykiv, Yurii Kulchytsky, Andrii Solohub, Anatol Yablonsky, and Temistokl Vyrsta. Omelian Mazuryk, who worked in an expressionist manner inspired by Byzantine-Ukrainian icons, came to Paris from Poland in 1968; Anton Solomukha from Kyiv, who has taken a postmodern approach to painting, came in 1978; and Volodymyr Makarenko, whose work is stylized and often symbolic, arrived there in 1980.

After the Second World War many Ukrainian artists fled from communist rule and settled in the West: Robert Lisovsky and R. Hluvko in Great Britain, Borys Kriukov and Volodymyr Lasovsky in Argentina, Vasyl H. Krychevsky, and Halyna Mazepa in Venezuela, and Mykhailo Kmit in Australia. Of the artists who settled in Canada Kateryna Antonovych, I. Belsky-Stetsenko, and Yuliian Butsmaniuk painted in a realist manner, and Myron Levytsky and Halyna Novakivska pursued a variety of semiabstract styles. Of those who settled in the United States, including Mykola Butovych, Mykhailo Dmytrenko, Sviatoslav Hordynsky, Liuboslav Hutsaliuk, Petro P. Kholodny, Edvard Kozak, Petro Mehyk, Mykhailo Moroz, Mykola Nedilko, Myroslav Radysh, Jurij Solovij, and Viktor Tsymbal, most worked in a variety of figurative styles and usually exhibited within the Ukrainian community. Jacques Hnizdovsky, who is known internationally for his wood engravings, was also an accomplished neorealist painter.

Some Ukrainian artists working in the United States were born in Ukraine, but matured and received their training mostly in America (R. Baranyk, B. Borzemsky, Anatol Kolomyiets, Sophia Lada, Chrystya Olenska, and Arcadia Olenska-Petryshyn). American-born artists of Ukrainian origin who have participated in exhibitions of Ukrainian art include Yaroslava Surmach-Mills, J. Gaboda, and L. Bodnar-Balahutrak.

Of the artists born in Canada William Kurelek gained international prominence for his convincing depictions of Ukrainian pioneers and other ethnic groups in Canada. Other more prominent artists on the Canadian art scene include Laryssa Luhovy, Adriane Lysak, Lillian Sarafinchan, Mariia Styranka, K. Kulyk, Peter Shostak, Natalka Husar, and Andrii Prychodko.

Changes brought about by glasnost and perestroika in the USSR resulted in greater creative freedom and a proliferation of styles and manners of depiction in Ukrainian art of the late 1980s and early 1990s. Artists whose work had been suppressed (eg, Opanas Zalyvakha, A. Antoniuk, Oleksandr Dubovyk, Ivan Marchuk, and Feodosii Humeniuk) have had solo exhibitions. Many painters have shown great inventiveness, including P. Hulyn from Uzhhorod, Roman Romanyshyn and Roman Zhuk from Lviv, Mykhailo Popov from Kharkiv, Oleksandr Tkachenko from Dnipropetrovsk, Oleh Nedoshytko and L. Diulfan from Odesa, and F. Tetianych, Tiberii Silvashi, V. Budnykov, Ye. Hordiits, M. Heiko, Borys Plaksii, and O. Babak from Kyiv. After decades of restraint and isolation artists in Ukraine are now free to continue the development of various artistic traditions and have prospects of rejoining the international artistic mainstream.

(See also Art, Fresco painting, Genre painting, Icon, Landscape art, Miniature painting, Modernism, Mural, Nonconformist art, Portraiture, Primitive art, and Realism.)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Zatenats’kyi, Ia. (comp). Ukraïns’ke obrazotvorche mystetstvo: Zhyvopys, skul’ptura, hrafika (Kyiv 1956, 1957)

Sichyns’kyi, V. Istoriia ukraïns’koho mystetstva (New York 1956)

Zatenats’kyi, Ia. Ukraïns’kyi radians’kyi zhyvopys (Kyiv 1958)

Bazhan, M.; et al (eds). Istoriia ukraïns’koho mystetstva, 6 vols in 7 bks (Kyiv 1966–70)

Zabolotnyi, V. (ed). Narysy z istoriï ukraïns’koho mystetstva (Kyiv 1966)

Afanasiev, V. Stanovlennia sotsialistychnoho realizmu v ukraïns’komu obrazotvorchomu mystetstvi (Kyiv 1967)

Bielichko, Iu. Tema. Ideia. Obraz: Tendentsiï rozvytku suchasnoho ukraïns’koho obrazotvorchoho mystetstva (1945–1972) (Kyiv 1975)

Lohvyn, H.; Miliaieva, L.; Svientsits’ka, V. (comps). Ukraïns’kyi seredn’ovichnyi zhyvopys: Al’bom (Kyiv 1976)

Pavlov, V. Suchasna ukraïns’ka akvarel’ (Kyiv 1978)

Zholtovs’kyi, P. Ukraïns’kyi zhyvopys XVII–XVIII st. (Kyiv 1978)

Pavlov, V. Ukraïns’ke radians’ke mystetstvo 1920–1930-kh rokiv (Kyiv 1983)

Mudrak, M. The New Generation and Artistic Modernism in the Ukraine (Ann Arbor 1986)

Zhaboriuk, A. Ukraïns’kyi zhyvopys ostann’oï tretyny XIX–pochatku XX st. (Kyiv 1990)

Pelens’ka, O. (comp). Biienale ukraïns’koho obrazotvorchoho mystetstva ‘L’viv ‘91—Vidrodzhennia’: Maliarstvo, hrafika, skul’ptura (Lviv 1991)

Marko, O.; Shkandrij, M.; Tracz, O.; Walsh, M. (eds). Spirit of Ukraine: 500 Years of Painting: Selections from the State Museum of Ukrainian Art, Kiev (Winnipeg 1992)

Daria Zelska-Darewych

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 3 (1993).]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)