History of Ukraine

History of Ukraine [Історія України; Istoriia Ukrainy]. Information on the earliest history of Ukraine is derived from archeological records and from general descriptions of the early Slavs by Greek, Roman, and Arab historians. Ukrainian national historiography has traditionally divided Ukrainian history into the following periods: (1) the so-called Princely era of Kyivan Rus’ and the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia; (2) the period of the Lithuanian-Ruthenian state; (3) the period of the Cossacks and the Hetman state; (4) the national and cultural revival of the 19th century; (5) the Ukrainian nation-state of 1917–21 [see Struggle for Independence (1917–20)]; (6) the interwar occupation of Ukrainian territories by four foreign powers; (7) the consolidation of most Ukrainian ethnic territory into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic; and finally, after 1991, (8) independent Ukraine (following the 1991 Ukraine’s Declaration of Independence). Because more than one political state often ruled Ukraine’s territories simultaneously and, at times, several Ukrainian governments coexisted (eg, those of the Hetman state and of Right-Bank Ukraine), dealing with Ukraine’s history presents many difficulties. Furthermore Western Ukraine experienced a historical development separate from that of central and eastern Ukraine, resulting in the evolution of the historical-political entities of Galicia, Volhynia, Bukovyna, and Transcarpathia. The only denominator unifying all of Ukraine’s lands and state formations throughout the centuries has been the Ukrainian people and its linguistic, social, cultural, and religious specificities.

Prehistory.

The Stone Age. The oldest traces of the presence of early humans on Ukrainian territories, dating back to the Lower Paleolithic Period (ca 900,000 BC), were discovered near Korolevo on the Tysa River in Transcarpathia (Korolevo archeological site) and near Medzhybizh on the Boh River in Podilia (Medzhybizh archeological site). Archeological evidence indicates that by the Upper Paleolithic Period (ca 44,000–12,000 BC) almost all of today’s Ukraine was inhabited by clans of hunters and gatherers. The northern Ukrainian territories were the stomping grounds for woolly mammoth and thereby attracted mammoth hunters. Significant archeological finds from such locations as Mizyn archeological site include numerous stone tools, but also masterful works of sculpture, ornamented jewelry, prehistoric musical instruments, and the earliest known reconstructable architectural structures: large mammoth-bone dwellings. The southern Ukrainian plains encompassed the ranges of the bison and reindeer and drew people who hunted them (Amvrosiivka archeological site).

During the Mesolithic Period (ca 10,000–5,800 BC) the inhabitants of Ukrainian lands (many of whom migrated at that time from other parts of Europe or from the Middle East) engaged in fishing, had domesticated dogs, and used the bow and arrow. The first tribal units likely appeared at this stage of prehistory. A remarkable archeological site and the oldest known prehistoric place of worship in Ukraine, which was in use at least as early as the Mesolithic Period, is Kamiana Mohyla situated in the Azov Lowland.

During the Neolithic Period in Ukraine (ca 5,800–4,500 BC; see Map: Neolithic Cultures), migrating farming communities from the Balkans and Danube region brought to Ukrainian territories primitive agriculture and animal husbandry, as well as wattle and daub architecture, pottery, and weaving. These industries were further developed both in settlements of these newcomers, such as those of the Linear Pottery culture, and by local autochthonous population (e.g., the Boh-Dnister culture). In the later stages of the Neolithic more technologically and culturally advanced Cucuteni-Trypillia groups established their early Trypillia culture villages along the Dnister River in today’s western Ukraine.

The Copper Age. The Eneolithic Period (Copper Age; early 5th–late 4th millennium BC; see Map: Eneolithic Cultures) coincided with the apex of the development of Trypillia culture. At its height, this culture occupied vast lands between the Carpathian Mountains and the Dnipro River, where it built numerous settlements, including several immense (with an area of up to 350 ha) ‘mega-sites’—the largest known human settlements of this prehistoric epoch. The Trypillia culture represented the northeastern province of the civilizational complex of ‘Old Europe’ and was, at that time, the most advanced branch of this cultural domain. It was an agricultural society remarkable for its technological and cultural advancements, such as monumental architecture, technologically complex pottery kilns, and sophisticated art objects, most notably, ceramic sculptures and fine, thin-walled, and masterfully ornamented pottery.

The steppes along the northern coast of the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov as well as the steppe and forest-steppe stretching east of the Dnipro River were populated by pastoralist tribes that subsisted on animal husbandry, hunting, and fishing, with agriculture playing only a minor role in their livelihood. These tribes developed a social system markedly different from that of the probably matrilineal Trypillia culture communities; this was a patriarchal system centred around tribal leaders. Many historians consider these tribes and the region of today’s southern and eastern Ukraine as the cradle of Indo-European peoples and cultures that were soon to play a crucial role in the historical development of Europe and parts of Asia.

The first generally recognized archeological culture of this Indo-European (or perhaps proto-Indo-European) complex was the Serednii Stih culture that appeared around 4,500 BC in the lower Dnipro Valley. Over centuries (ca 4,500 to 3,500 BC), this culture metamorphosed into a broader Serednii Stih horizon that included distinct, but related Novodanylivka culture, Deriivka culture, Lower Mykhailivka culture, and others. In spite of essential civilizational differences, these pastoralist Indo-European tribes developed fairly close relations with the Trypillians. The remarkable Usatove culture that emerged in the mid-4th millennium BC on the northwestern shores of the Black Sea is generally considered to have been a mixture of Trypillia culture and various steppe influences.

The forests of northern Ukraine, especially the Polisia region, were inhabited by less culturally developed tribes of the Dnipro-Donets culture and, further northeast, Pit-Comb Ware culture. The regions of Volhynia and northern Podilia were, over centuries, the domain of several mixed agricultural-pastoral cultures, such as the Lublin-Volhynia culture, Funnelbeaker culture, and Globular Amphora culture. The distinctive region of Transcarpathia was the home to Eneolithic communities of the Tiszapolgár culture and later Bodrogkeresztúr culture.

The Bronze Age. At the dawn of Bronze Age in the late 4th millennium BC, a powerful Indo-European Yamna culture (aka Pit-Grave culture) appeared in the Lower Dnipro region and then quickly spread to encompass vast territories of the steppes from the northwestern Black Sea region to the Ural Mountains in the east. The rise to prominence of these pastoralist tribes was brought about by various factors, including radical climate changes that took place at the end of the 4th millennium BC and led to the collapse of the agriculture-based economy of the Trypillians. Within several centuries, the highly-developed Trypillia culture ceased to exist and its technological and cultural achievements disappeared as most of them were not adopted by the Indo-European tribes that overtook Trypillian territories.

In the early Bronze Age the majority of Ukrainian lands—especially in the steppe and forest-steppe zones—were controlled by the carriers of the Yamna archeological culture complex. Initially the forest-steppe and forests of northern Ukraine were the domain of the Middle-Dnipro culture, while northwestern regions of Volhynia and northern Podilia were inhabited by the tribes of the Globular Amphora culture. Over a few centuries, the Middle-Dnipro culture evolved into the nucleus of the powerful and warlike Corded Ware culture that fairly quickly extended its territories far to the west—to the Rhine River—and to the east—to the Volga (where some related tribes may have developed independently at the same time). Along with the Yamna archeological culture complex, the Corded Ware culture exerted a profound impact on the dispersal of Indo-European peoples and languages in Europe and parts of Asia. Much smaller territories of today’s Ukraine were populated by the representatives of other archeological cultures: the Kemi-Oba culture (in the Crimea) and Baden culture (in Transcarpathia).

Although the first migrations of pastoralist tribes from the steppe of today’s southern Ukraine to the Balkans and Central Europe took place as early as ca 4,200 BC, it was in the early 3rd millennium BC that this process took on a more massive character. The carriers of the Yamna archeological culture complex migrated in considerable numbers on wagons along the Danube River into Central Europe and beyond. At the same time, other Yamna groups from the Pontic-Caspian steppe roamed east into Asia. Somewhat later the tribes of the Corded Ware culture also moved west and east, carrying with them their pastoralist way of life, patriarchal social system, and Indo-European dialects. These migrations marked the end of the era of ‘Old Europe’ and the beginning of the Indo-European domination of Europe and parts of Asia.

This process of ‘Indo-Europeanization’ of Europe and parts of Asia, in which migrants from the territories of today’s Ukraine played a key role, took close to two millennia. During that time Ukrainian territories were inhabited by a number of distinctive archeological cultures. These include: the Catacomb culture (of the Middle Bronze Age), Babyne culture, Timber-Grave culture (Zrubna), and Sabatynivka culture (of the Late Bronze Age), and Bilozerka culture (of the Final Bronze Age). Archeological cultures in the northern territories of Ukraine, where proto-Slavic tribes were being formed, included the Marianivka culture, Bilohrudivka culture, Strzyżów culture, Komariv culture, and Trzciniec culture; most of these cultures were subgroups of the Corded Ware culture. In the Carpathian Mountains region and Transcarpathia resided the carriers of the Baden culture, Stanove culture, Noua culture, and others. The western regions of Ukraine during the Bronze Age saw the eastern expansion of Urnfields cultures, such as the Lusatian culture and Wysocko culture, as well as late Hallstatt culture, represented in Ukraine by the Gáva-Holihrady complex. In the final stage of Bronze Age on Ukrainian territories another radical climate change caused a considerable increase in steppe aridity and prompted another westward migration of the local population. At the same time, newcomers from the east ushered with them a new era of the Iron Age.

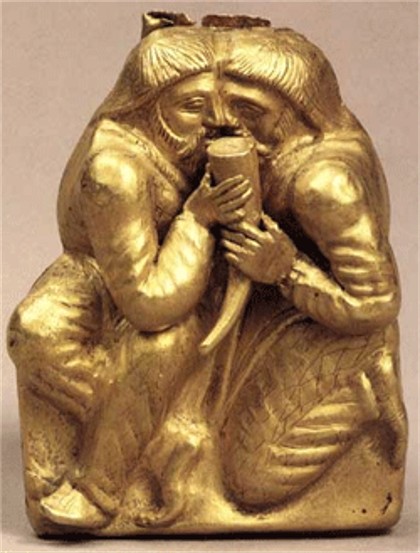

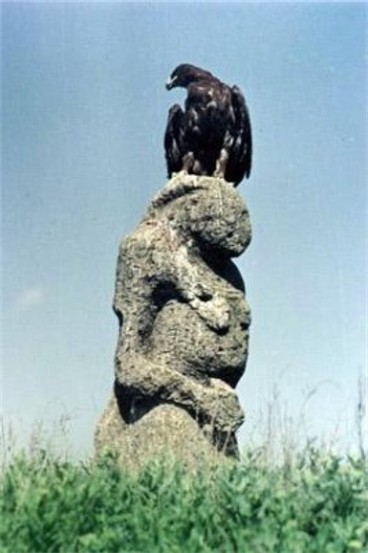

The Iron Age. During the Iron Age, significant changes occurred in the material culture of Ukraine’s inhabitants, particularly in agriculture, metallurgy, and commerce. In the early 1st millennium BC Iranian peoples—Cimmerians—appeared in the basin of the Dnipro River and Boh River in southern Ukraine. Archeological evidence shows that they, like the tribes of the indigenous Timber-Grave culture, Bilohrudivka culture, Bondarykha culture, and Chornyi Lis culture, had iron implements. In the 8th century BC, the Cimmerians were displaced by the Scythians, tribes of nomadic horsemen from Central Asia that intermingled with and assimilated the indigenous peoples and founded an empire that lasted until the 2nd century BC, and even longer in the northern Crimea. The Scythians’ political and economic hegemony in the region was established after they repulsed the invasion of King Darius of Persia in 513 BC.

From the 7th century BC, Greek city-states founded trading colonies on the northern Pontic littoral. With time these towns became independent poleis (see Ancient states on the northern Black Sea coast), which interacted and traded with the other peoples of the region, particularly the Scythians, Taurians, Maeotians, Sindians, and Getae. In the late 5th century BC, the Hellenic towns on the Kerch Peninsula of the Crimea and Taman Peninsula united to form the Bosporan Kingdom. In the 1st century BC the Hellenic states were annexed by the Romans and remained under Roman rule until the invasions of new nomadic peoples: the Sarmatians, Alans, and Roxolani, Iranian-speaking tribes from Central Asia that had appeared in the Pontic steppes in the 4th century BC and had conquered most of the Scythians’ territories by the 2nd century BC. Subsequently the Germanic tribes of the Goths arrived on Ukrainian territories in the late 2nd century AD from the Baltic region and conquered the Sarmatians and other indigenous peoples. In the 3rd century the Goths waged war against the Romans and took most of their colonies on the Pontic littoral. Gothic rule collapsed in 375 under the onslaught of the Huns; most of the Goths fled west beyond the Danube River, and only a small number of them remained in the Crimea.

The Hunnic invasion of Europe initiated what is known as the great migration of peoples from the East. After the Huns, the Ukrainian steppes were invaded by the Volga Bulgars in the 5th century, the Avars in the 6th, the Khazars in the 7th, the Magyars in the 9th, the Pechenegs and Torks in the 10th and 11th, the Cumans in the 11th and 12th, and the Mongols in the 13th century.

By the 2nd century BC, Ukraine’s forest-steppe regions, Polisia, and part of the steppe were inhabited by the agricultural proto-Slavic tribes of the Zarubyntsi culture; western Ukraine was populated by the tribes of the Przeworsk culture. By the 2nd century AD, the tribes of the Cherniakhiv culture populated large parts of the Ukrainian forest-steppe. Most scholars consider the territory bounded by the middle Dnipro River, the Prypiat River, the Carpathian Mountains, and the Vistula River to be the cradle of the ancient Slavs. By the 4th century AD, the eastern Slavs of Ukraine had organized themselves into a tribal alliance called the Antes, whose domain stretched through the forest-steppe and steppe zones from the Dnister River to the Don River. In the early 6th century the Antes established relations with the Byzantine Empire, against which they also waged war in the Balkans. Their state lasted until the 6th century, when it was destroyed by the Avars and most of the Antes fled north to resettle in the upper Dnipro Basin. During these centuries, the forest and forest-steppe zones in western, northwestern, and northern Ukraine were populated by the tribal confederation called the Sklavenes in the Greek sources. Like the Antes, the Sklavenes also established a strong tribal alliance, which too was destroyed by the Avars in the 6th century. Although very significant numbers of Antes and Sklavenes migrated as a result of the Avar onslaught, major sections of these Slavic populations remained on Ukrainian territories, where they played key roles in the ethnogenesis of the Ukrainians.

By the 6th century AD, the ancestors of the Ukrainians were divided into several tribal groups: the Polianians on the banks of the Dnipro River around Kyiv; the Siverianians in the Desna River, Seim River, and Sula River basins; the Derevlianians in Polisia between the Teteriv River and Prypiat River basins; the Dulibians, later called Buzhanians and Volhynians, in the Buh River basin; the White Croatians in Subcarpathia; the Ulychians in the Boh River basin; and the Tivertsians in the Dnister River basin. These tribes had ties with the proto-Belarusian Drehovichians, the proto-Russian Radimichians, Viatichians, and Krivichians, and the Baltic tribes to the north; the Bulgarian Kingdom (see Bulgaria) and the Byzantine Empire to the south; the Khazar Kaganate and the Volga Bulgars to the east; and the proto-Polish Vistulans and Mazovians, Great Moravia, and the Magyars to the west. They also traded with more distant lands via international trade routes: the route ‘from the Varangians to the Greeks’ linking the Baltic Sea and Black Sea mostly via the Dnipro River and thus joining Scandinavia with Byzantium (see Varangian route); the east-west route from the Caspian Sea to Kyiv and then to Cracow, Prague, and Regensburg, thus joining the Arab world with central and western Europe; and the route linking the Caspian and Baltic seas and thus the Arab world with Scandinavia. Because they lived along or at the crossroads of these important trade routes, the proto-Ukrainian tribes played an important economic and political role in eastern Europe.

The tribes shared a common proto-Slavic language and pagan beliefs. They built their agricultural settlements around wooden fortified towns. Kyiv was the capital of the Polianians; Chernihiv, of the Siverianians; Iskorosten (Korosten), of the Derevlianians; Volyn (Horodok on the Buh River), of the Dulibians; and Peresichen, of the Ulychians. The Polianians were the most developed of the tribes; according to the Rus’ Primary Chronicle, their prince, Kyi, founded Kyiv in the late 6th century. Kyiv’s strategic position at the crossroads of the trade routes contributed to its rapid development into a powerful economic, cultural, and political center. The tribal princes, however, were not able to transform their tribal alliances into viable states and thus protect their independence. In the early 8th century, the Polianians and Siverianians were forced to recognize the supremacy of the Khazar kaganate and to pay tribute. In the mid-9th century, the warlike Varangians from Scandinavia invaded and conquered the tribal territories, and established the foundations for Kyivan Rus’ state with its capital in Kyiv.

The Princely era. The leading role in the Kyivan Rus’ state until its demise some five centuries later was played by the princes (whence the name: the Princely era). The Primary Chronicle states that the Eastern Slavs had invited the Varangians to rule over them. This source was later used to substantiate the so-called Normanist theory of the origins of Kyivan Rus’. The Riurykide dynasty that ruled Rus’ and other East European territories until 1596, presumably originated with the legendary Varangian Prince Riuryk of Novgorod. The most outstanding Varangian ruler of Kyivan Rus’ was Prince Oleh (Oleg), who, reportedly, succeeded Riuryk in Novgorod ca 879. In 882 he killed Askold and Dyr and took power in Kyiv, which became the capital of his realm. He then conquered most of the East Slavic tribes, thus becoming the undisputed ruler of a vast and mighty state. After consolidating his power and eliminating the influence of the Khazars on his territory, Oleh undertook an expedition against Constantinople, forcing it to sue for peace and to pay a large indemnity in 907. In 911 he concluded an advantageous trade agreement and laid the basis for permanent trade links between Kyivan Rus’ and the Byzantine Empire.

The efforts of Prince Oleh’s successor Prince Ihor (Igor, 912–45) to gain control of the northern Black Sea littoral led to war with Byzantium and to a new treaty with Constantinople, in which the trade privileges obtained by Oleh were significantly curtailed. Throughout his reign, Ihor tried to consolidate the central power of Kyiv by pacifying the rebellious neighboring tribes. The Derevlianians, who fiercely defended their autonomy, captured and killed Ihor during one of his attempts to extort tribute from them.

Prince Ihor’s widow Princess Olha (Olga, 945–62), who was possibly a Slav, ruled Rus’ until her son Sviatoslav I Ihorovych came of age. During her reign the Slavic members of her court gained ascendancy. Olha converted to Christianity by 957. She established direct contacts with Constantinople and links with West European rulers.

Sviatoslav I Ihorovych (962–72), known as ‘the Conqueror,’ expanded the borders and might of Rus’. He waged a successful war against the Volga Bulgars and destroyed the Khazar kaganate. The elimination of the Khazars had negative consequences, however: it opened the way for the invasion of Kyivan Rus’ by new Asiatic tribes. Sviatoslav expanded the frontiers of his realm to the Caucasus Mountains and then conquered the Bulgarians (967–8), establishing Pereiaslavets on the Danube River as his stronghold in the Danube region. Threatened by his encroachments, Constantinople declared war on Sviatoslav. After initial victories in Macedonia, Sviatoslav was defeated and forced out of Bulgaria in 971. On his way back to Kyiv with a small retinue, he was ambushed by Pecheneg mercenaries of the Byzantines near the Dnipro Rapids and died in battle.

Yaropolk I Sviatoslavych (972–80) ruled over Kyiv after his father’s death. He wanted to unite the entire kingdom under his rule and succeeded in killing Oleh Sviatoslavych, but his brother Volodymyr escaped and hired Varangian mercenaries, with whose help he killed Yaropolk.

Volodymyr the Great (980–1015) thus united under his rule the lands acquired by his predecessors and proceeded to extend his territory. He waged an ongoing struggle from 988 to 997 with the Pechenegs, who were constantly attacking Rus’ towns and villages, and built a network of fortresses to protect Kyiv.

After his conquests, Volodymyr the Great ruled the largest kingdom in Europe, stretching from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sea of Azov and Black Sea in the south and from the Volga River in the east to the Carpathian Mountains in the west. To administer his scattered lands, he created a dynastic seniority system of his clan and members of his retinue (druzhyna), in which the role of the Varangians was diminished. To give his vast domain a unifying element Volodymyr adopted Byzantine Christianity as the state religion, was baptized, and married Anna, the sister of the Byzantine emperor Basil II.

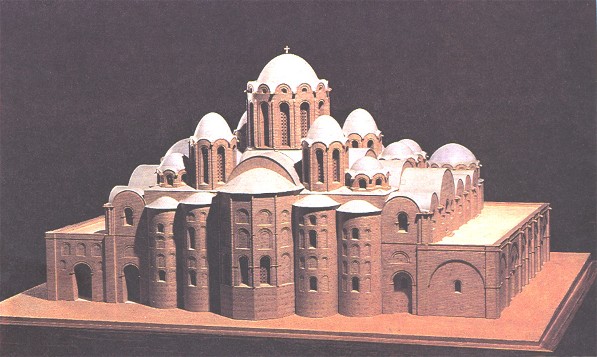

The official Christianization of Ukraine in 988 had important consequences for the life of Kyivan Rus’ (see also History of the Ukrainian church). The unity of the state and the authority of the grand prince were strengthened. Byzantine art, architecture, literature, and teaching were introduced and adopted by the princes, boyars, and upper classes. Many churches and monasteries were built, and the clergy became a powerful cultural and political force.

During his reign, Volodymyr the Great began minting coins stamped with the symbol of a trident. (During the struggle for independence (1917–20) and again since 1992 the trident has served as Ukraine’s national emblem.)

Towards the end of his life, Volodymyr’s sons Sviatopolk I and Yaroslav (by then prince of Novgorod the Great) rebelled against his authority. When Volodymyr died in 1015, a bitter struggle for hegemony ensued among his sons, which lasted till 1036 when Yaroslav established control over most of the Kyivan state.

During the reign of Yaroslav the Wise (1019–54) the Kyivan state attained the height of its cultural development. Yaroslav also paid much attention to the internal organization of his state. He built fortifications to defend his steppe frontier. He promoted Christianity, established schools, and founded a library at the Saint Sophia Cathedral (in 1036 to commemorate his victory over the Pechenegs). During Yaroslav’s reign the Kyivan Cave Monastery was founded in 1051; it became the pre-eminent center of monastic, literary, and cultural life in Kyivan Rus’. Yaroslav had the customary law of Rus’ codified in the Ruskaia Pravda in order to regulate economic and social relations, which were becoming more complex. An important development that occurred during his rule was the rise of an indigenous, Slavic political elite in the Kyivan state that included such figures as Yaroslav’s adviser Dobrynia, Dobrynia’s son Konstantyn (Yaroslav’s lieutenant in Novgorod), and Vyshata Ostromyrych (the governor of Kyiv). Thenceforth the role of the Varangians was limited, even as mercenaries. In 1051 Yaroslav convoked a synod of bishops and installed, without having asked for the consent of the ecumenical patriarch, the first metropolitan of Kyiv who was not a Greek, but a local Rus’ (Ruthenian). Metropolitan Ilarion governed the Rus’ church until about 1065. Yaroslav’s influence spread far and wide because he arranged dynastic alliances with nearly all the reigning families of Europe.

Before his death in 1054, Yaroslav the Wise divided his realm among his five remaining sons. Yaroslav maintained the principle of seniority introduced by his father, according to which the eldest son inherited Kyiv and the title of grand prince, while the other sons were to respect the eldest and help him administer the entire polity of Kyivan Rus’. In the event of the death of the eldest son, his place was to be taken by the next eldest, and so forth. The seniority principle did not survive the test of time, however. As the sons and their offspring prospered in the lands they inherited, their interests conflicted with one another and with the interests of state unity. Internecine strife developed, provoking the eventual collapse of the Kyivan state.

The last of Yaroslav the Wise’s sons on the Kyivan throne, Vsevolod Yaroslavych (1078–93), directly ruled the principal lands of Kyivan Rus’: Kyiv principality, Chernihiv principality, Pereiaslav principality, Smolensk principality, Rostov principality, and Suzdal principality. In the last years of his reign, Vsevolod’s realm was administered by his son Volodymyr Monomakh of Pereiaslav.

Vsevolod Yaroslavych was succeeded in Kyiv by his nephew Sviatopolk II Iziaslavych (1093–1113), whose reign was distinguished by his continuous wars with the Cumans. With his cousin, Volodymyr Monomakh, Sviatopolk undertook successful expeditions against the invaders in 1103, 1109, and 1111.

The Cuman menace and ongoing wars among the princes were the subject of the 1097 Liubech congress of princes near Kyiv. Called at the initiative of Volodymyr Monomakh, the princes altered the principle of patrimony. It was decided that sons had the right to inherit and rule the lands of their fathers, thus annulling the seniority system created by Yaroslav the Wise, and that Kyivan Rus’ would be subdivided into autonomous principalities, whose rulers would, nonetheless, obey the grand prince in Kyiv.

The consensus reached at Liubech was short-lived. Conflicts among the princes once again began pitting the Rostyslavych branch (sons of Rostyslav Volodymyrovych), Monomakh branch, and Sviatoslavych branch (descendants of Sviatoslav II Iaroslavych) of the Riurykide dynasty against Davyd Ihorovych and Sviatopolk II Iziaslavych. To settle the conflicts and organize campaigns against the Cumans, the Vytychiv congress of princes (1100) and Dolobske council of princes (1103) were held.

When Sviatopolk II Iziaslavych died, the common people responded to the social and economic oppression of his regime with the Kyiv Uprising of 1113. The alarmed boyars turned to Volodymyr Monomakh to restore order and to ascend the Kyivan throne. The popular Monomakh (1113–25) began his reign by amending the Ruskaia Pravda (see Volodymyr Monomakh's Statute). He was the last of the grand princes who strove to curtail the internecine wars among the princes in order to maintain the unity and might of Kyivan Rus’. As before, Monomakh concentrated on combating the Cumans, whom he drove back to Caucasia and the Volga River early in his reign, renewing short-lived Slavic expansion into the steppe. During Monomakh’s reign, Rus’ flourished culturally. Many churches were built, the Kyivan Cave Patericon was begun, and the writing of chronicles, hagiography, and other literature thrived. Before his death Monomakh wrote his famous testament, Poucheniie ditiam (instruction for [My] Children), a work of literary value in which he instructed his sons how to be strong and just rulers.

Volodymyr Monomakh was succeeded by his eldest son Mstyslav I Volodymyrovych (1125–32), who inherited the lands of Kyiv, Smolensk, and Novgorod the Great; the remaining lands of Kyivan Rus’ were distributed among his brothers. Mstyslav’s authority stemmed from his ability to organize the princes in combating the Cumans’ renewed invasions. Like his father, he maintained ties with the rulers of Europe.

The political and social institutions of Kyivan Rus’. From the 10th to the 12th century the Kyivan state underwent significant sociopolitical changes. Volodymyr the Great was the first ruler to give Kyivan Rus’ political unity, by way of organized religion. The church provided him with the concepts of territorial and hierarchical organization; Byzantine notions of autocracy were adopted by him and his successors. The grand prince maintained power by his military strength, particularly through his druzhyna or retinue. He ruled and dispensed justice with the help of his appointed viceroys and local administrators—the tysiatskyi, sotskyi, and desiatskyi.

Members of the druzhyna had a dual role: they were the prince’s closest counselors in addition to constituting the elite nucleus of his army. Its senior members, recruited from among the ‘better people’ or those who had distinguished themselves in combat, soon acquired the status of barons called boyars. The prince consulted on important state matters with the Boyar Council. The viche (assembly) resolved all matters on behalf of the population and it became particularly important during the internecine wars of the princes for the throne of Kyiv.

The privileged elite in Kyivan Rus’ was not a closed estate (see Estates); based as it was on merit, its membership was dependent on the will of the prince. The townsfolk consisted of burghers—mostly merchants and craftsmen—and paupers. Most freemen were yeomen, called smerds. A smaller category of half-free peasants were called zakups. The lowest social strata in Kyivan Rus’ consisted of slaves.

The disintegration of the Kyivan state. During the reign of Mstyslav I Volodymyrovych’s successor and brother, Yaropolk II Volodymyrovych (1132–9), widespread dynastic rivalry for the crown of the ‘grand prince of Kyiv and all of Rus'’ arose between the Olhovych house of Chernihiv and the Monomakhovych clans. These internecine wars continued for a century, during which time the throne of Kyiv principality changed hands almost 50 times.

As a result of the wars, Kyiv’s primacy rapidly declined. In 1169 Prince Andrei Bogoliubskii of Vladimir, Rostov, and Suzdal sacked Kyiv and left it in ruins. Thereafter the title of grand prince of Kyiv became an empty one, and the autocratic rulers of Vladimir were a constant threat to the Ukrainian principalities of southern Rus’, as were the Cumans. From the mid-12th century, Kyiv principality, Polatsk principality, Turiv-Pynsk principality, Volodymyr principality, Halych principality, Chernihiv principality, and Pereiaslav principality developed as politically and economically separate units. In 1136 Novgorod the Great became a sovereign mercantile city-republic tied to the Baltic cities of the Hanseatic League and the Slavic hinterland and controlled by a boyar oligarchy.

Galicia assumed the leading role among the Ukrainian principalities during the reign of its prince Volodymyrko Volodarovych (1124–53). The reigns of his son Yaroslav Osmomysl (1153–87), who extended the territory of Halych principality to the Danube River Delta, and grandson Volodymyr Yaroslavych (1187–99) were marked by frequent struggles with the powerful Galician boyar oligarchy.

Volhynia gained prominence under the reign of the Monomakhovych dynasty beginning in the 1120s. After a half-century of individual, fragmented autonomy, the appanage Volodymyr principality and Lutsk principality and the Berestia land were reunited under the rule of Prince Roman Mstyslavych (1173–1205). In 1199 Roman was invited by the Galician boyars to become the ruler of Halych principality.

The historical fate of Transcarpathia, which until the late 10th century was ruled by the Kyivan state, was different. After the death of Volodymyr the Great, the Hungarian king, Stephen I, took advantage of the internecine struggles that arose in Kyivan Rus’ to annex Transcarpathia; except for a few short periods, it remained part of Hungary until 1918. The other western borderlands, Bukovyna and Bessarabia, were part of Kyivan Rus’ from the 10th century, and it was only after the demise of the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia that they became part of Moldavia.

The Galician-Volhynian state (1199–1340). As the ruler of the newly created Principality of Galicia-Volhynia, and particularly after he conquered the lands of Kyiv principality in 1202, Roman Mstyslavych reigned over a large and powerful state, which he defended from the Yatvingians and Cumans. When he died the boyar oligarchy took control in Galicia.

Prince Leszek of Cracow and King Andrew II of Hungary exploited the succession crisis and civil strife: Leszek occupied most of Volhynia, and Andrew placed his son Kálmán on the throne of princely Halych in 1214 as ‘King of Galicia and Lodomeria.’ In 1221 Mstyslav Mstyslavych of Novgorod the Great, to whom the boyars had appealed for help, defeated the Hungarians, occupying the Galician throne until 1228. By 1230 Danylo Romanovych and Vasylko Romanovych were able to consolidate their rule in Volhynia, and in 1238 they drove the Hungarians, to whom Mstyslav had restored Galicia in 1228, from Galicia.

Yet the threat from the east continued. The Mongols entered Kyivan Rus’ and routed the united armies of the Rus’ princes under the command of Mstyslav Mstyslavych and Danylo Romanovych at the Kalka River in 1223. A large army of Mongols led by Batu Khan invaded Rus’ again in 1237, devastated the Pereiaslav principality and Chernihiv principality in 1239, sacked Kyiv in 1240, and penetrated into Volhynia and Galicia, where it razed most of the towns, including Volodymyr (in Volhynia) and princely Halych in 1241.

Danylo Romanovych, the outstanding ruler (1238–64) of Galicia-Volhynia, after defeating the Teutonic Knights at Dorohychyn in 1238, subduing the rebellious boyars in 1241–2, and defeating Rostyslav Mykhailovych of Chernihiv and his Polish-Hungarian allies at Jarosław in 1245, prepared to overthrow the Mongol yoke. His attemps at forming a military coalition with the Papacy, Hungary, Poland, and Lithuania against the Mongols did not succeed, however, and in 1255 Danylo relied on his own forces to defeat the Mongols and their vassals between the Dnister River and Boh River and in Volhynia. But the massive Mongol offensive of 1259, led by Burundai, forced him to submit to the authority of the Golden Horde.

The Principality of Galicia-Volhynia declined steadily under Danylo Romanovych’s successors Lev Danylovych (1264–1301), Yurii Lvovych (1301–15), Lev Yuriiovych and Andrii Yuriiovych (corulers 1315–23), and Yurii II Boleslav (1323–40). After the death of Yurii II, rivalry among the rulers of Poland, Hungary, Lithuania, and the Mongols for possession of Volhynia and Galicia ensued. The Lithuanian duke Liubartas became the ruler of Volhynia and the Kholm region. The Polish king Casimir III the Great attacked Lviv in 1340, but it was not until 1349 that he was able to defeat the Galician boyars led by Dmytro Dedko and to occupy Galicia. Casimir’s successor, Louis I of both Hungary (1342–82) and Poland (1370–82), ruled Galicia through his vicegerents, among them Władysław Opolczyk. In 1387, Louis’s daughter Queen Jadwiga annexed Galicia and the Kholm region to Poland.

Ukraine under Lithuanian and Polish rule. While the Ukrainian principalities declined under onslaughts of the Asiatic nomads, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania rose to prominence in the Baltic region. Gediminas (1316–41) annexed the Belarusian and Ukrainian land of Chorna Rus’, the Vitsebsk land, Minsk land, Berestia land, Turiv-Pynsk principality, Volhynia, and the northern Kyiv region. In 1323 Gediminas assumed the title of ‘Lithuanian, Samogitian, and Ruthenian (Rus’) grand duke.’ To consolidate his realm, he fostered dynastic ties by marrying his daughters to Ruthenian (Belarusian and Ukrainian) princes and promoting Ruthenian culture. Algirdas (1345–77) enlarged the grand duchy by conquering the Ukrainian lands of the Chernihiv principality, Novhorod-Siverskyi principality, and, after defeating the Tatars at Syni Vody in 1363, Kyiv principality, Pereiaslav principality, and Podilia.

Thus, nine-tenths of the grand duchy became composed of autonomous Ukrainian and Belarusian territories. Until 1385 the intermarriage of Ruthenian and Lithuanian princely families strengthened the Ruthenian influence in Lithuania, which many scholars have referred to as the Lithuanian-Ruthenian state. As members of the grand duke’s privy council, high-ranking military commanders, and administrators (vicegerents), Ruthenian nobles became part of the ruling elite. Ruthenian became the official state language and Orthodoxy the prevailing religion (10 of Algirdas’s 12 sons were Orthodox). Under Algirdas’s son and successor Jogaila, the Lithuanian-Ruthenian state was threatened by the Teutonic Knights, Tatars, and Muscovy. To gain support Jogaila agreed to marry the Polish queen Jadwiga, share her throne, and unite Lithuania with Poland. After the Union of Krevo of 1385, Jogaila became King Władysław II Jagiełło of Poland as well as remaining the grand duke of Lithuania. Although the grand duchy retained its independence, the Polish nobility made inroads there, resulting in a strong Lithuanian-Ruthenian backlash against Polonization and Catholicism.

Opposition to this union was led by Vytautas the Great, whose popularity and alliance with the Teutonic Knights forced Jagiełło to recognize him in 1392 as grand duke of all Lithuanian-Ruthenian lands. Under his rule (1392–1430) the grand duchy incorporated all the lands between the Dnister River and Dnipro River as far south as the Black Sea and reached the summit of its greatness. After his defeat by the Tatars in battle at the Vorskla River in 1399, however, Vytautas was forced to abandon his expansionist plans in the east and seek an accord with Jagiełło. The Lithuanian-Polish Union of Horodlo of 1413 curtailed the participation of the Orthodox (and thus the Ruthenians) in governing the state and allowed only Catholics to remain in the Lithuanian state council.

Towards the end of the 15th century a new external menace arose—the Crimean Khanate, which seceded from the Golden Horde and in 1478 became a vassal of Ottoman Turkey. As the ally of Grand Prince Ivan III of Muscovy, Lithuania’s enemy, Khan Mengli-Girei (see Girei dynasty) sacked Kyiv in 1482. From then on the Tatars regularly raided and ravaged the Ukrainian lands. Lithuania was unable to prevent these raids, nor could it stop Muscovy from annexing a large part of its Ruthenian lands, including northern Chernihiv principality and Novhorod-Siverskyi principality. With the support of Muscovy, certain Ruthenian princes, led by Mykhailo Hlynsky, who proclaimed himself grand duke, rebelled against Lithuanian Catholic rule in 1508. The rebellion was quelled, however, and the Hlynsky and other noble families fled to Muscovy. Thus ended the last attempt by the Ruthenian princes to secede from Lithuania.

Lithuania and Poland’s ongoing wars with Muscovy and the Tatar threat during the reigns of Alexander Jagiellończyk (1492–1506), Sigismund I the Old (1506–48), and Sigismund II Augustus (1548–72) created the need for close collaboration, mutual defense, and a movement for a real, and not just dynastic, union of the two states. The Lithuanian-Ruthenian lower nobility supported unification, for it would give them the privileges and freedoms enjoyed by the szlachta in the Polish parliamentary monarchy. The princes and magnates opposed it, however, for it would mean the loss of their authority (see Council of Lords). In January 1569 the Sejm in Lublin failed to reach an accord on the union, and Sigismund II annexed Podlachia, Volhynia, and the Kyiv region and Bratslav region—over one-third of the grand duchy—to Poland. After further negotiations and conflicts the Union of Lublin was signed on 1 July 1569. Thereafter Poland and Lithuania constituted a single, federated state—the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth—ruled by a jointly elected monarch; the state was to have a common Diet, foreign policy, currency, and property law. Both partners were to retain separate administrations, court systems, treasuries, armies, and laws, however. Because Poland now possessed the larger territory, it had greater representation in the Diet and thus became the dominant partner. The only Ukrainian lands left in the grand duchy were parts of the Berestia land and Pynsk region.

With the Union of Lublin, the Lithuanian-Ruthenian period—the only period of full-fledged feudalism in Ukrainian history—came to an end. Thereafter the Ukrainian lands, for the most part, constituted the Rus’ voivodeship, Belz voivodeship, Podilia voivodeship, Podlachia voivodeship, Volhynia voivodeship, Bratslav voivodeship, Kyiv voivodeship, and, from 1635, Chernihiv voivodeship within the Polish crown. There the Lithuanian Statute—the legal code of the Lithuanian-Ruthenian state—remained in effect, but Ukrainian as the official language was supplanted by Polish and Latin. Nevertheless Ukrainian princes continued to own large estates and thus maintained their former privileged positions. On the territory of Volhynia, in particular, there remained a large number of influential Ukrainian nobles—eg, the Ostrozky, Vyshnevetsky (Wiśniowecki), Koretsky, Kysil, Chartoryisky (Czartoryski), Chetvertynsky (Sviatopolk-Chetvertynsky), Zbarazky (Zbaraski), and Zaslavsky (Zasławski) families. The Polish king, however, began distributing ownership charters to the ‘empty’ lands in Right-Bank Ukraine to a small number of Polish and Polonized Ukrainian magnates; thus arose the huge latifundia—virtually autonomous domains—of the Potocki, Zamoyski, Sieniawski, Kalinowski, Tyszkiewicz (Tyshkevych), Zbaraski (Zbarazky), Koniecpolski, and Wiśniowiecki (Vyshnevetsky) families in Ukraine.

The integration of the Ukrainian lands into Poland resulted in significant national and religious transformations. Part of the relatively small Ukrainian elite, particularly the magnates, became Polonized as a result of the influence of Polish education and of the large number of in-migrating Polish nobles and Catholic clergy (especially the Jesuits). Even many prominent Ukrainian families, including that of Prince Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozky, a leading defender of Orthodoxy, converted to Roman Catholicism and readily adopted Polish language and culture.

Under the new regime, the noble-dominated cities and towns grew in size and number and experienced an economic boom. It was, however, almost exclusively the Catholic German and Polish burghers who benefited from self-government by Magdeburg law. The Orthodox Ukrainian burghers were the victims of persecution and segregation; this incited them to organize brotherhoods in order to defend and promote their national, cultural, and corporate interests.

The peasants gained nothing from the Union of Lublin. Fully subjected to the nobles and their agents, they were forced to perform increasingly more corvée labor and were restricted in their right to move from one landlord to another. Conditions in the newly colonized lands of the Dnipro River basin were somewhat better, owing to their relative underpopulation. There, in order to attract peasant settlement, the nobles introduced the sloboda—an agricultural settlement whose inhabitants were exempted temporarily from feudal obligations.

The rule of the Polish ‘nobles,’ the Polonization, economic exploitation, and religious and national-social oppression provoked organized forms of protest: the growth of Protestantism, particularly of the Socinians, among the Ukrainian nobility; the above-mentioned Orthodox burgher brotherhoods and brotherhood schools; and attempts by the déclassé Orthodox hierarchy and clergy to gain parity with their Roman Catholic counterparts, culminating in the 1596 Church Union of Berestia and the creation of the Uniate or Greek Catholic church. The church union was not accepted by the majority of the Ukrainian population, however, and many Ukrainian nobles, led by Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozky, as well as the brotherhoods actively opposed it. The religious struggles that ensued found their written expression in polemical literature. (See also History of the Ukrainian church.)

The Cossacks. From the 15th century onward, thousands of men, some seeking opportunity, some escaping serfdom, settled in the Commonwealth-Tatar steppe frontier. To defend themselves from Tatar attacks, they organized armed groups and fortified settlements. With time they also began attacking the Tatar and Turkish settlements on the Black Sea. In 1552–4, Prince Dmytro Vyshnevetsky united various Cossack groups and founded a Cossack fortress on Mala Khortytsia Island south of the Dnipro Rapids. This became the first of several Cossack centers called the Zaporozhian Sich, the nucleus of the quasi-democratic Cossack domain that became known as the Zaporizhia (‘land beyond the rapids’).

The Cossacks’ expeditions against the Tatars and Turks made them famous throughout Europe. In 1577 they marched on Moldavia to help one of their own, Ivan Pidkova, become the hospodar there. In 1594, Alexander Komulovich and Erich Lassota von Steblau, the envoys of Pope Clement VIII and Emperor Rudolph II, enlisted Cossack mercenaries under Hryhorii Loboda and Severyn Nalyvaiko in the war against the Turks. These and other manifestations of Cossack military and political autonomy were a threat to the Polish regime, for they provoked Tatar and Turkish retaliation in Ukraine. As early as 1572, Sigismund II Augustus tried to circumscribe the Cossacks’ growth and freebootery by creating a register of 300 royal Cossacks, who were granted privileges, liberties, land, and money in return for military service to the crown. The institution of these so-called registered Cossacks, whose number increased (at times to 6,000) during Poland’s wars, provoked discontent among the magnates, who opposed any ennoblement of the Cossacks, as well as social divisions and discord among the Cossacks as a whole. Those not ‘registered’ were officially considered peasants and subject to feudal obligations. These and other measures precipitated rebellions led by Kryshtof Kosynsky (1591–3) and Nalyvaiko and Loboda (1594–6) (in which registered Cossacks participated) against the magnates in Ukraine. The latter rebellion in particular involved many burghers and peasants, and engulfed large parts of Right-Bank Ukraine and Belarus; it was brutally suppressed by the crown army led by Stanisław Żółkiewski, and Polish oppression in Ukraine intensified.

In the first quarter of the 17th century, Poland needed the Cossacks in its wars with Turkey (in Moldavia), Sweden (in Livonia), and Muscovy. The crown therefore restored the civil rights it had abolished after the Kosynsky rebellion and reinstated the register of Cossacks. At that time the Cossacks assumed a more political role as the defenders of outlawed Orthodoxy, which cemented their ties with the burghers and peasants; the unceasing defense of their corporate rights prepared them for their future role as the vanguard of a national revolution. Hetman Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny (1614–22), the renowned leader of Cossack sea expeditions against the Tatar towns in the Crimea (1606–17), succeeded in creating a disciplined, regular Cossack army. In 1618 his army took part in the campaign of Prince Władysław (see Władysław IV Vasa) against Moscow, and in 1621 the united Polish-Cossack army halted the Turkish advance on central Europe at the Battle of Khotyn. A protector of Orthodoxy, in 1621 Sahaidachny played a key role in persuading the Patriarch of Jerusalem to renew the church hierarchy of the Ukrainian Orthodox church and consecrate Yov Boretsky as metropolitan of Kyiv. Sahaidachny pursued a conciliatory policy vis-à-vis the Polish Crown. The king, however, would not recognize the new Orthodox hierarchs, and soon after Khotyn any privileges the Cossacks had been granted for their wartime role were abrogated.

Although in this period the Cossacks were cognizant of their strength, they were not united in their attitude to the Polish regime. One group, consisting of the registered Cossacks, sought a compromise with the Poles. The other, the unprivileged majority, led by Olyfer Holub, ignored the Polish injunctions. They remained recalcitrant, and in 1624–5 even fought on land and sea against Turkey as the allies of the Crimean khan Mohamet-Girei III. The Polish king, seeing his relations with Turkey endangered, sent the crown army under Stanisław Koniecpolski to subdue the Zaporozhian Cossacks. Hetman Marko Zhmailo and his successor Mykhailo Doroshenko were forced to sign the Treaty of Kurukove, which limited the number of registered Cossacks to 6,000 and the Cossacks’ freedom in general. But peace did not last long. The 1630 Zaporozhian rebellion, led by Taras Fedorovych (Triasylo), forced the Poles to negotiate the Pereiaslav Treaty of 1630, which increased the register to 8,000 but failed, as before, to appease the Zaporozhian Cossacks, who continued their raids against the Turks.

In 1632 the registered Cossacks, led by Ivan Petrazhytsky-Kulaha, demanded that they, as a loyal, obedient, knightly estate (see Estates), be allowed to take part in the election of the new king after the death of Sigismund III Vasa. The Diet in Warsaw that elected Władysław IV Vasa legalized the Orthodox church and recognized its church hierarchy to mollify the Ukrainians and counter pro-Muscovite attitudes. Under Petro Mohyla, the new metropolitan of Kyiv (1633–47), the Ukrainian Orthodox church experienced a renaissance, as did Ukrainian education, scholarship, and culture in general (see Kyivan Mohyla Academy).

King Władysław IV Vasa was much more liberal toward his Ukrainian subjects than Sigismund III Vasa had been. But although the Cossacks helped him in his wars with Sweden, Muscovy (during which the Chernihiv region was captured by Poland), and Turkey, he did not recognize their demands for increased privileges. Consequently, many Cossacks continued to flee to the Zaporizhia. To stop this exodus the Polish government built a fort in Kodak in 1635, but the Cossacks, led by Hetman Ivan Sulyma, razed it. The general dissatisfaction with Polish rule resulted in a new uprising in 1637, led by Pavlo Pavliuk. The rebels were defeated in the Battle of Kumeiky 1637 and forced to accept even greater restrictions. In the spring of 1638, a rebellion again erupted, this time in Left-Bank Ukraine, under the leadership of Dmytro Hunia, Yakiv Ostrianyn, and Karpo Skydan. Having fought several battles, the rebels finally surrendered at the Starets landmark. After this event the number of registered Cossacks was limited to 6,000, their senior officers, the so-called Cossack starshyna, were appointed by the Polish nobles, the hetman was replaced by a Polish commissioner, burghers and peasants were forbidden to marry Cossacks or join their ranks, Cossacks could reside only in Chyhyryn, Korsun, or Cherkasy districts, unregistered Cossacks were outlawed, the Kodak fortress was rebuilt, and Polish garrisons were stationed throughout Ukraine. For a decade thereafter the Polish magnate kinglets kept the Cossacks in check and intensified their exploitation and oppression of Ukrainian Orthodox peasants and burghers. This ‘golden tranquility’ was broken by yet another uprising, this time on a much greater scale.

The Khmelnytsky era. The great uprising of 1648 was one of the most cataclysmic events in Ukrainian history. It is difficult to find an uprising of comparable magnitude, intensity, and impact in the history of early modern Europe.

A crucial element in the revolt was the leadership of Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky (1648–57), whose exceptional organizational, military, and political talents to a large extent accounted for its success. The uprising engulfed all of Dnipro Ukraine. Polish nobles, officials, Uniates, and Jesuits were massacred or forced to flee. Jewish losses, estimated at over 50,000 during what became a decade-long Cossack-Polish War, were especially heavy, because the Jews, who were concentrated in Ukraine in large numbers, were seen as agents of the Polish szlachta. Great massacres were also perpetrated against the Ukrainian populace by the retreating Poles, led by the magnate Jeremi Wiśniowiecki. The Poles were crushed at the Battle of Zhovti Vody on 16 May 1648 and again in September, at the Battle of Pyliavtsi in Volhynia where the Cossacks were joined by the peasants en masse. Poland proper was now defenseless, but Khmelnytsky, after briefly occupying western Ukraine and besieging Lviv and Zamość, decided, because of oncoming winter and doubts about the chances of success of a full-scale invasion of Poland, to return to Dnipro Ukraine. Upon his triumphant entry into Kyiv, he declared that although he had begun the uprising for personal reasons he was now fighting for the sake of all Ukraine.

By April 1649, it was clear that Khmelnytsky was contemplating a separation of Ukraine from the Polish Commonwealth, and the Commonwealth armies, led by the new king, Jan II Casimir Vasa, and Prince Janusz Radziwiłł, launched a counteroffensive. Defeated once again at the Battle of Zboriv on 15 August, the Poles sued for peace and the Treaty of Zboriv was signed on 18 August 1649. The Poles, however, broke the treaty in 1651 and with the help of the Tatars, under Islam-Girei III, defeated the Cossacks at the Battle of Berestechko; and Khmelnytsky was forced to conclude the Treaty of Bila Tserkva in September 1651. The treaty allowed the Poles to return to much of Ukraine.

Realizing that he could not defeat the Poles by military means alone and hoping to expand his political base, Khmelnytsky turned to diplomacy. In September 1650 he dispatched a large Cossack force to Moldavia in the hope of installing his son, Tymish Khmelnytsky, there. The hetman envisaged the creation of a great coalition backed by the Ottomans, Tatars, and Danubian principalities and consisting of Ukraine, Transylvania, Brandenburg, Lithuania, and even Oliver Cromwell’s England. His aim was to restructure the Commonwealth into an equal union of Poland, Lithuania, and Ukraine with Prince György II Rákóczi of Transylvania as its new king. Khmelnytsky’s plans suffered a great setback when the Moldavian boyars revolted and his son died in battle in 1653. Another major setback occurred during the siege of Zhvanets in Podilia in December 1653: Khmelnytsky was about to annihilate the army of Jan II Casimir Vasa when his Tatar allies signed a separate peace with the Poles. Khmelnytsky then abandoned his orientation on the Ottomans and Tatars and drew closer to Muscovy.

Tsar Aleksei Mikhailovich agreed to help Bohdan Khmelnytsky ‘for the sake of the Orthodox faith,’ expecting also to regain some of the lands Muscovy had previously lost to Poland, to utilize Ukraine as a buffer zone against the Ottomans, and, in general, to expand his influence. The Pereiaslav Treaty of 1654 established an alliance of Ukraine and Muscovy. The Poles responded to the new alliance by combining forces with the Tatars. A new expanded phase of conflict began. In 1654, while a combined Muscovite-Ukrainian army (see Ivan Zolotarenko) scored major successes in Belarus, the Poles and, especially, the Tatars devastated Ukraine. A year later it was Poland that experienced devastation, when the Swedes, taking advantage of the war, invaded the country. Sensing the imminent demise of the Commonwealth, György II Rákóczi of Transylvania concluded an alliance with Khmelnytsky, and in January 1657 a large Ukrainian-Transylvanian force was sent into Poland to expedite its partition.

Khmelnytsky’s foreign policy, especially his co-operation with the Swedes, who were also at war with Muscovy, raised the tsar’s ire. But Khmelnytsky also had his grievances: he was bitter over the imposition of Muscovite rule in Belarus, where the populace had expressed preference for a Cossack government; even more infuriating was the Vilnius Peace Treaty with the Poles in October 1656, which Moscow had concluded without consulting the hetman. Mutual recriminations followed, and there were signs that the hetman was reconsidering the link with Moscow. Then the Ukrainian-Transylvanian offensive in Poland collapsed. Crushed by these setbacks and already ill, Khmelnytsky died on 6 August 1657.

The Hetman state. At the time of Bohdan Khmelnytsky’s death, the Cossacks controlled the former Kyiv voivodeship, Bratslav voivodeship, and Chernihiv voivodeship, an area inhabited by about 1.5 million people. About 50 percent of the land, formerly owned by the Polish crown, became the property of the Zaporozhian Host, which, in return for taxes, allocated it to self-governing peasant villages. Cossacks and Ukrainian nobles retained approximately 33 percent of the land, and the church, 17 percent. The entire area was divided into 16 military and administrative regions corresponding to the territorially based regiments of the Cossack army (see Regimental system). Initially, the Cossack starshyna (senior officers) were elected by their units, but in time these posts often became hereditary.

At the pinnacle of the Cossack military-administrative system stood the hetman. Assisting the hetman was the General Officer Staff, which functioned as a general staff and a council of ministers. The formal name of the new political entity was the Zaporozhian Host; the Muscovites, however, referred to it as Little Russia, while the Poles continued calling it Ukraine.

Hoping to establish a dynasty, Bohdan Khmelnytsky had arranged for his 16-year-old son Yurii Khmelnytsky to succeed him. It soon became apparent, however, that the young boy was incapable of ruling, and Ivan Vyhovsky was chosen hetman (1657–9). Vyhovsky hoped to establish an independent Ukrainian principality. His elitist and pro-Polish tendencies engendered a rebellion by the rank-and-file town Cossacks and Zaporozhian Cossacks, led by Martyn Pushkar and Yakiv Barabash and covertly backed by Moscow. Vyhovsky emerged victorious from this internal struggle but militarily and politically weakened. Realizing that a confrontation with Moscow was inevitable, Vyhovsky entered into negotiations with the Poles regarding the return of Ukraine to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In September 1658 they concluded the Treaty of Hadiach. Viewing the treaty as an act of war, Moscow dispatched a large army into Ukraine. In July l658, it was crushed at the Battle of Konotop by a combined force of Poles, Ukrainians, and Tatars. But Vyhovsky’s politics continued to elicit opposition, and several Cossack leaders (Ivan Bohun, Ivan Sirko, Ivan Bezpaly) rose in revolt. Realizing that his base of support was crumbling, in September 1659 the hetman fled to Poland.

The Cossack starshyna, hoping that the appeal of his name would help to heal internal conflicts, elected Yurii Khmelnytsky hetman (1659–62). The Muscovites, who returned to Ukraine with another large army, forced the young hetman to renegotiate the Pereiaslav Treaty of 1654 and sign the Pereiaslav Articles of 1659. The new pact was a major step forward in Moscow’s attempts to tighten its hold on Ukraine: it increased the number of Muscovite governors and garrisons in the Hetman state, forbade the hetman from maintaining foreign contacts without the tsar’s permission, and stipulated that election of Cossack leaders should be confirmed by Moscow. Disillusioned, Khmelnytsky went over to the Poles in 1660, helped them defeat the tsar’s army at Chudniv, and signed the Treaty of Slobodyshche. The regiments of Left-Bank Ukraine, led by Yakym Somko, refused to follow Khmelnytsky, however, and remained loyal to the tsar. Unable to cope with the strife and chaos, Khmelnytsky resigned in 1663. A period of constant war and devastation began.

The Ruin. During this period, called the Ruin by contemporaries, Ukraine was divided along the Dnipro River into two spheres of influence, the Polish in Right-Bank Ukraine and the Muscovite in Left-Bank Ukraine and Kyiv. At times, the Ottoman presence was felt in the south. All Cossack hetmans during this period were dependent on these powers for support. The hetmans’ weakness stemmed largely from internal conflicts, especially the ongoing social tensions between the Cossack starshyna and the rank-and-file Cossacks and peasants, who resented the attempts of the starshyna to monopolize political power and impose labor obligations upon them. Consequently, political factionalism, opportunism, and adventurism became prevalent among the Cossack leaders, who were easily manipulated by Ukraine’s powerful neighbors.

Two typical hetmans of the period were Pavlo Teteria (1663–5) in Right-Bank Ukraine and Ivan Briukhovetsky (1663–8) in Left-Bank Ukraine. Teteria, who adhered strictly to a pro-Polish line, invaded the Left Bank together with the Poles in 1664 and urged its Cossacks to march on Moscow. When the offensive failed, Teteria and the Poles (see Stefan Czarniecki) returned to the Right Bank (see Ivan Popovych, Varenytsia Uprising); their brutality in quelling numerous anti-Polish uprisings aroused such animosity that Teteria was forced to abdicate and flee to Poland.

On the Left Bank, Briukhovetsky’s policy toward Moscow was exceedingly conciliatory (see Baturyn Articles). The first Ukrainian hetman to pay homage to the tsar (for which he received the title of boyar, estates, and the daughter of Prince Dmitrii Dolgoruky in marriage), he signed the Moscow Articles of 1665, which significantly increased Muscovy’s political, military, fiscal, and religious control. These concessions, the hetman’s high-handedness, the behavior of the Muscovite governors and tax collectors, and the Treaty of Andrusovo (1667)—an armistice that ratified the partition of Ukraine between Poland and Muscovy—infuriated the populace and led to widespread revolts against Briukhovetsky and the Muscovite garrisons. Briukhovetsky’s attempts at backing away from Moscow and heading the revolt against it failed to appease the rebels, and in 1668 he was killed by an angry mob.

An attempt to preserve Cossack Ukraine from chaos and to reassert Ukrainian self-government in the Hetman state was made by the popular colonel of Cherkasy and hetman of Right-Bank Ukraine, Petro Doroshenko (1666–76). After the Poles signed the Treaty of Andrusovo, Doroshenko turned against them and resolved to unite all of Ukraine under his rule. To gain the support of the rank-and-file Cossacks, he agreed to hold frequent meetings of the General Military Council, and to free himself from overdependence on the powerful colonels, he established mercenary Serdiuk regiments under his direct command. In fall 1667, a combined Cossack-Ottoman force compelled King Jan II Casimir Vasa to grant the hetman wide-ranging authority over the Right Bank. Doroshenko then invaded Left-Bank Ukraine and, after Ivan Briukhovetsky’s demise in 1668, was proclaimed hetman of all Ukraine. During his absence from the Right Bank, however, the Zaporozhian Cossacks proclaimed Petro Sukhovii hetman; soon after, the Poles returned and established Mykhailo Khanenko as yet another rival hetman. Returning to confront his adversaries, Doroshenko appointed Demian Mnohohrishny acting hetman (1668–72) on the Left Bank. A Muscovite army invaded the Left Bank, however, and Mnohohrishny was forced to swear allegiance to the tsar (see Hlukhiv Articles) in 1669.

Ukraine was divided again. Weakened, Petro Doroshenko was forced to rely increasingly on the Ottomans. In 1672 his forces joined the huge Turkish-Tatar army that wrested Podilia away from the Poles (see Buchach Peace Treaty of 1672), and in 1674–7 he found himself fighting on the side of the Turks against the Orthodox forces of the tsar and of the new hetman of Left-Bank Ukraine, Ivan Samoilovych. Compromised by his association with the Muslim occupation and the ravages of the civil war, the now unpopular Doroshenko surrendered to Samoilovych in 1676.

To replace Petro Doroshenko in the ongoing struggle between the Porte and Moscow for Right-Bank Ukraine during the Chyhyryn campaigns, 1677–8, the Ottomans resurrected Yurii Khmelnytsky as the ‘Prince of Ukraine’ (1677–8, 1685). The 1681 Peace Treaty of Bakhchysarai left much of southern Right-Bank Ukraine a deserted neutral zone between the two empires. No longer in need of Khmelnytsky, the Ottomans had him executed, and pashas governed the Right Bank from Kamianets-Podilskyi.

From 1669 Left-Bank Ukraine remained under Muscovite control (see Little Russian Office) and was spared the recurrent Ottoman, Tatar, Polish, and Muscovite invasions that devastated the once flourishing Right-Bank Ukraine. Although Demian Mnohohrishny, like Ivan Briukhovetsky, was elected hetman there with Muscovite acquiescence, he did not intend to be a puppet of the tsar. This was evident from his demands that Moscow limit its military presence in the cities to Kyiv, Nizhyn, Pereiaslav, and Chernihiv. With the help of mercenary regiments, he managed to establish order on the Left Bank, but his constant conflicts with the increasingly entrenched Cossack starshyna brought about his downfall.

Demian Mnohohrishny’s successor Ivan Samoilovych (1672–87) made loyalty to Moscow and cordial relations with the starshyna the cornerstones of his policy. He thus managed to remain hetman for an unprecedented 15 years. To win over the starshyna, he awarded the members generous land grants and created the so-called fellows of the standard (a corps of junior officers), thereby encouraging the development of a hereditary elite in Left-Bank Ukraine. Like all hetmans, Samoilovych attempted to extend his authority over all of Ukraine. He tightened his control over the unruly Zaporozhian Cossacks, and from 1674 he fought alongside the Muscovites against Petro Doroshenko and the Turks. Greatly disappointed by his and Muscovy’s failure to conquer the devastated Right-Bank Ukraine, he organized the mass evacuation of its inhabitants to the Left-Bank Ukraine and Slobidska Ukraine. The Polish-Muscovite Eternal Peace of 1686 and anti-Muslim coalition validated Poland’s claims to Right-Bank Ukraine and placed the Zaporizhia lands under the direct authority of the tsar instead of the hetman. Consequently, Samoilovych was not overly co-operative when Muscovy launched a huge invasion of the Crimea in 1687. Blamed by the Muscovite commander Vasilii Golitsyn and the Cossack starshyna for the failure of the campaign, Samoilovych was deposed and exiled to Siberia.

After Poland recovered Right-Bank Ukraine from Turkey in 1699 and the Zaporozhian Cossacks asserted their autonomy, only about a third of the territory of the Hetman state, or Hetmanate, that Bohdan Khmelnytsky established remained under the authority of the hetmans. Situated now mostly in Left-Bank Ukraine, the Hetmanate consisted of only 10 regiments. While the structure of Cossack self-government underwent only minor changes, major shifts occurred in the socioeconomic structure of the Left Bank. By the late 17th century, the Cossack starshyna had virtually excluded rank-and-file Cossacks from decision-making and higher offices, and the latter’s political decline was closely related to their mounting economic problems. Individual Cossacks took part in the almost endless wars of the 17th and early 18th centuries at their own expense. Consequently many of them were financially ruined, and this caused a decline in the number of battle-ready Cossacks and in the size of the Cossack army. In 1700 the Hetmanate’s army numbered only about 20,000 men. Moreover, the equipment, military principles, and tactics on which the Cossacks relied had become increasingly outdated. Confronted by internal weaknesses, leading a depleted military force, and disillusioned by the behavior of the Poles and Ottomans during the Ruin, most Cossack leaders no longer questioned the need to maintain links with Moscow. But they were still committed to preserving what was left of the rights guaranteed to them by the Pereiaslav Treaty of 1654.

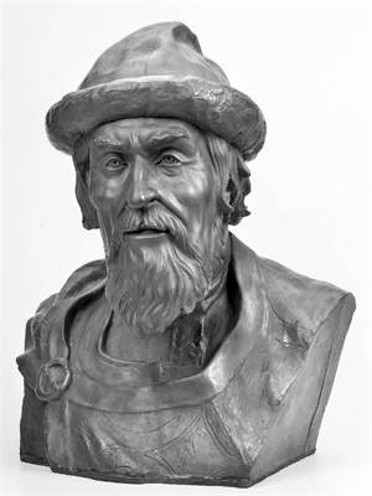

The Ivan Mazepa era. A decisive phase in the relationship of the Hetman state to Moscow occurred during the hetmancy of Ivan Samoilovych’s successor Ivan Mazepa (1687–1708/9), one of the most outstanding and controversial of all Ukrainian political leaders. For most of his years in office Mazepa pursued the traditional, pro-Muscovite policies of the Left-Bank Ukraine hetmans. He continued to strengthen the Cossack starshyna, issuing them over 1,000 land grants (see Kolomak Articles), but he also placed certain limits on their exploitation of the lower classes. The largess of the tsars made him one of the wealthiest landowners in Europe. Mazepa used much of his wealth to build, expand, and support many churches and religious, educational, and cultural institutions. His pro-starshyna policies, however, engendered discontent among the masses and the anti-elitist Zaporozhian Cossacks and resulted in a dangerous but unsuccessful Tatar-supported Zaporozhian uprising led by Petro Petryk in 1692–6.

A cardinal principle of Ivan Mazepa’s policy was the maintenance of good relations with Moscow. He developed close relations with Tsar Peter I, energetically helping him in his 1695–6 Azov campaigns against the Tatars and Turks. He was also his adviser in Polish affairs. These close contacts helped him gain Muscovite backing for the occupation of Right-Bank Ukraine in 1704 during the great anti-Polish Cossack revolt led by Semen Palii. Once again Ukraine was united under the rule of one hetman. But as the Northern War (1700–21), in which Charles XII of Sweden and Peter I were the main opponents, progressed, dissatisfaction with Muscovite rule spread in the Hetmanate. The Cossack regiments suffered huge losses during difficult campaigns in the Baltic Sea region, Poland, and Saxony; the civilian populace had to support Muscovite troops and work on fortifications; and Peter’s reforms threatened to eliminate Ukrainian autonomy and integrate the Cossacks into the Muscovite army. Pressured by the disgruntled starshyna, Mazepa began having doubts about Moscow’s overlordship. In 1705 Stanislaus I Leszczyński, Charles’s Polish ally, secretly proposed to him to bring Ukraine into the Polish-Lithuanian federation. In October 1708, after the tsar informed Mazepa that he could not count on Moscow’s aid should the Swedes and Poles invade Ukraine, Mazepa decided to join the advancing Swedes. In July 1709, Charles and Mazepa were defeated in the decisive Battle of Poltava and fled to Ottoman Moldavia, where the aged and dejected hetman died.

About 50 leading members of the Cossack starshyna, almost 500 Cossacks from the Hetman state, and over 4,000 Zaporozhian Cossacks followed Ivan Mazepa to Bendery. These ‘Mazepists’ were the first Ukrainian émigrés (see Emigration). In the spring of 1710 they elected Pylyp Orlyk, Mazepa’s general chancellor, as their hetman-in-exile. Anxious to attract potential support, Orlyk drafted the Constitution of Bendery. With Charles XII’s backing, he concluded anti-Muscovite alliances with the Tatars and the Ottoman Porte and in January 1711 launched a combined Zaporozhian-Tatar offensive in Ukraine. After initial successes, the campaign failed.

The decline of Ukrainian autonomy

Left-Bank Ukraine. After the failure of Ivan Mazepa’s plans, the absorption of the Hetman state into the Muscovite tsardom—and later, after Tsar Peter I formally adopted for his state the name Russia (Rossiia) and proclaimed it an empire (1721), into the Russian Empire—began in earnest. It was, however, a long, drawn-out process, which varied in tempo, because some Russian rulers were more dedicated centralizers than others, and during certain times it was dangerous to antagonize the Ukrainians (particularly in the course of war with the Ottomans). To weaken Ukrainian resistance, the imperial government used a variety of divide-and-conquer techniques: it encouraged conflicts between the hetmans and the Cossack starshyna, cowed the latter into submission by threatening to support the peasantry, and used complaints by commoners against the Ukrainian government as an excuse to introduce Russian administrative measures.

With the acquiescence of the tsar, Ivan Skoropadsky was chosen hetman (1708–22). Several Muscovite innovations followed his election. In violation of tradition, no new treaty was negotiated, and the tsar confirmed Ukrainian rights only in general terms (see Reshetylivka Articles of 1709). Peter I appointed a Muscovite resident, accompanied by two Muscovite regiments, to the hetman’s court with supervisory rights over the hetman and his government. The hetman’s residence was moved from Baturyn to Hlukhiv, closer to the Muscovite border. Peter began the practice of personally appointing colonels, bypassing the hetman, while the resident received the right to confirm other officers. Many of the new colonels were Muscovites or other foreigners, and for the first time Muscovites, particularly Aleksandr Menshikov, acquired large landholdings in Ukraine (many of them expropriated from the Mazepists). Even publishing was controlled by Peter’s decree of 1720, which forbade publication of all books in Ukraine with the exception of liturgical texts, which, however, were to be published only in the Muscovite redaction of Church Slavonic.

In 1719 Ukrainians were forbidden to export their grain and other products directly westward. Instead, they had to ship through Muscovite-controlled Riga and Arkhangelsk, where the prices were dictated by the Muscovite government. Muscovite merchants, meanwhile, received preferential treatment in exporting their goods to the Hetmanate. Tens of thousands of Cossacks were sent north to build the Ladoga canal and the new capital of Saint Petersburg, where many of them died from overwork, malnutrition, and unsanitary conditions. As a final blow to the autonomy of the hetman, Peter I instituted the Little Russian Collegium on 29 April 1722. Established supposedly to look after the tsar’s interest by controlling finances and to hear appeals against any wrongdoings of the Cossack starshyna, it seriously undermined the position of the hetman. Ivan Skoropadsky protested vehemently but to no avail. Soon after its establishment he died.

While Pavlo Polubotok was acting hetman (1722–4), a struggle for power developed between him and Gen Stepan Veliaminov, the head of the Little Russian Collegium. Refusing to give ground to the Collegium, Polubotok improved several aspects of the hetman government, especially the judiciary, so as to deprive Muscovites of an excuse for interference. To reduce peasant grievances, he pressured the starshyna to be less blatant in exploiting the peasantry. Polubotok’s and the starshyna’s repeated entreaties to restore their privileges, abolish the Collegium, and appoint a hetman (see Kolomak Petitions) angered Peter I and he responded by increasing the authority of the Collegium. Soon afterward, Polubotok and his colleagues were ordered to Saint Petersburg and imprisoned there. Polubotok died in prison. His colleagues were pardoned after Peter’s death in 1725.

With Pavlo Polubotok incarcerated, the Little Russian Collegium had free rein in the Hetmanate. In 1722 it introduced direct taxation of the Ukrainians. But, when Stepan Veliaminov demanded that Muscovites in Ukraine, and especially the influential Aleksandr Menshikov, also pay taxes, he lost support in Saint Petersburg. Moreover, the possibility of a new war with the Ottoman Empire raised the need to appease the Ukrainians. Therefore, in 1727, Emperor Peter II, influenced by Menshikov, abolished the Collegium and sanctioned the election of a new hetman, Danylo Apostol (1727–34).

The new hetman’s diplomatic, military, and political prerogatives were limited. Aware that any attempt to restore the hetman’s political rights was doomed, Danylo Apostol concentrated on improving social and economic conditions. He regained, however, the right to appoint the General Officer Staff and colonels, greatly reduced the number of Muscovites and other foreigners in his administration, brought Kyiv, long under the authority of Muscovite governors, under his sway, and had the number of Muscovite regiments in Ukraine limited to six. Thus, he slowed the process of the Hetmanate’s absorption into the Russian Empire.

After Danylo Apostol’s death, the new empress, Anna Ivanovna (1730–40), forbade the election of a new hetman and established a new board, the Governing Council of the Hetman Office (1734–50), to rule the Ukrainians. Its first president, Prince Aleksei Shakhovskoi, received secret instructions to spread rumors blaming the hetmans for taxes and mismanagement and to persuade Ukrainians that the abolition of the Hetman state would be in their interest. Russian political practices, such as that of obligatory denunciation (slovo i delo), were introduced in Ukraine in this period. Because of the Russo-Turkish War of 1735–9, during which Ukraine served as a base, the Cossacks and peasants suffered tremendous physical and economic losses. During the council’s existence the Code of Laws of 1743, which had been begun under Danylo Apostol, was completed but never implemented.